The talk I gave on Friday 14 June 2019 at the National is about courtship and forbidden love in the Edwardian period (mostly) and is linked to the theatre’s showing of Githa Sowerby’s Rutherford and Son (1912). It’s a fascinating play for its contribution to one of the hottest debates around marriage and society at the time: the way patriarchy, capitalism and the logics of family finance and consolidation all conspired to make marriage a ‘trade’ in which women, essentially property, inevitably got ripped off.

The patriarch in Rutherford and Son, John Rutherford, is obsessed with who will inherit his firm, and sees his children merely as investments in it. When their hearts and romantic inclinations lead them off the harshly capitalist path set out for them by Rutherford, his iron grip on the family tightens unbearably. Sowerby, herself a Fabian, was writing at a time in which feminists were lambasting what they saw as the dehumanisation of the romantic contract and were calling for marriage to be made a private contract – something that suited those involved, rather the vast edifices of church, state, family, society and capital. A wide range of critics saw that any improvements to the marital state would hinge only women being given more economic independence. To these critics, it was obvious that a wife’s forced reliance on a male breadwinner created the worst possible conditions for marriage.

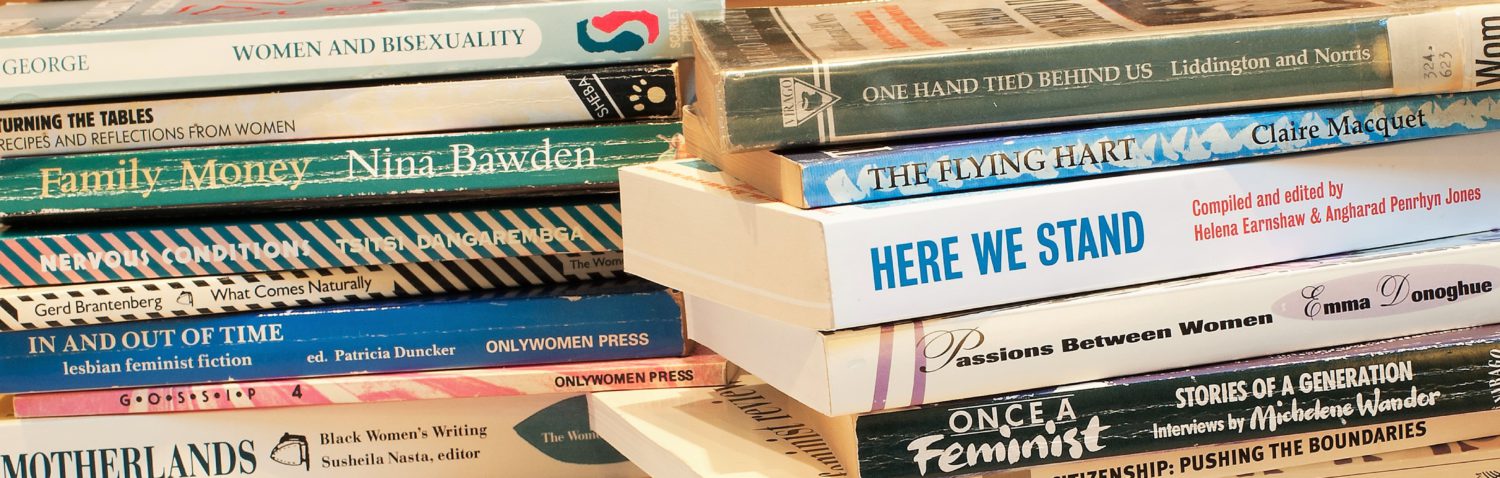

If we flash forward to the 1970s, a moment in which gender relations were once again being radically reconfigured, we can draw out some interesting continuities. If Edwardian feminists wanted to overhaul romantic relationships by ensuring that women – through financial independence – were no longer treated as male property, then the feminists of the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) were experimenting with leaving traditional capitalist structures behind entirely.

Those who still wanted to pursue heterosexual relationships wanted to do so anew, along socialist lines of caring and sharing, and in new types of non-commercial settings. One way they did so was in their living and working arrangements. As testimonies in the Sisterhood and After archive, held at the British Library, make clear, many WLM women lived with male partners in squats, or other communal housing arrangements. Often rent was minimal or free, and both men and women took turns doing housekeeping. Many of these men and women were working for councils, cooperatives, or collective endeavours in the arts and publishing, such as Spare Rib, which paid very little – Spare Rib workers earned around £30 per week in the early 1980s (about £105 today). There would later be heated exchanges about salaries evaporating even further, and contributors to Spare Rib remaining unpaid, but many women felt that the cause, not the pay, should be the driving factor. Crucially, as former Spare Rib workers interviewed as part of BOWW have made clear (Roisin Boyd; Rose Ades; Farzaneh), negligible pay was only possible in the particular setting of the 1970s and first part of the 1980s, thanks to squatting culture, the dole, and – in London – substantial aid from the Greater London Council.

The socialist ethos extended beyond even the most radical Edwardian visions, to sharing each other, and a number of interviews in Sisterhood and After, such as with Sheila Rowbotham and Sally Alexander, testify to the pain of these experiments.

One of BOWW’s undertakings has been to map the spaces and places in which the women’s liberation movement played out and the kinds of events that took place under its auspices. While many of these were women-only, they weren’t all. Regardless, by tracking Spare Rib listings throughout the magazine’s run (1972-1993), we see a movement that succeeded in creating a new social and cultural economy, an alternative to the naked commercialism and consumerism that, by mid-century, had come to dominate and romantic and social life. Those orbiting the movement could experience its promise away from the pressures of expensive food and drink, commercial trappings of romance, and – especially – the economic aspirationalism of coupledom. This was a world of women’s bands performing at women’s nights in pubs; of women’s theatre productions; of talks and discussions at libraries, of marches, demos, meetings and workshops at centres, of film screenings – many of them collectively run, all with substantial discounts for the poor or unwaged. These women’s partners, if they were male, inhabited a parallel world, a socialist ecosystem of state-aided, volunteer-run spaces, events and places.

But the social landscape built by the WLM seems a particularly resonant, even triumphant, project. The Edwardian feminists’ great-great grand-daughters had succeeded in creating a world in which women could explore themselves, not only away from the strains of heterosexual relationships, but also away from the relentlessness pressure construct their relational lives through the prism of commerce.

Leave a Reply