writes IDS Doctoral Researcher and Tutor Ru–Yu Lin

*The views in the following article are the personal views of the author and are not an official position of the School.*

When people ask me what my research focuses on, my answer tends to deliver a romanticised version of reality, since I conducted part of my research in the Easter Himalayas.

The Himalayan Mountain system ranges across Bhutan, India, Nepal, China, and Pakistan. My research focuses on the area between Tibet and Assam. Himalaya means ‘abode of the snow’ however, the snow reduction in this area has been an alarming issue in the past three decades.

I have worked in a very small village during my fieldwork, using anthropological methods with a development studies kind of twist. The village, including the neighboring three natural settlements, has no more than 2000 registered residents, and half of the population is constantly on seasonal migration. Migrants have two arrays of setting out and returning: moving along with experienced highland cattle or moving down to the lowlands, to study or work. Resource–wise, their intentions and aspirations are not hugely different. But the process of shifting the destinations could tell us more about the most important driver of social and economic change in two generations. That is the further integration with the nation–state and capitalist market. The courses of the epistemological change of the small–scattered human settlement in the Himalayan region are quite similar.

These people used to perceive the environment entirely as part of a belief system about life. In this system, every entity has a name, and there is no general concept of nature or culture.

My research question was written in alignment with the language that includes terms like nature and culture. Thus, my first assignment was on how to find the common ground between these two worldviews.

When I tried to figure out their rule of categorization by the wording, and interpret the unspoken parts, I engaged with the speakers, followed the landscape, and pronounced everything’s name with owe. By calling them by their name, I was introducing myself to the entities I was calling. For example, the waterbody and watercourse have myths and Godlike guardians attached to them, and some words describe the fertility of the soil or the origin of rain – abstract and philosophical information. I feel that these words, along with the experience of living close to my researched community for a while, turned me into a ‘worker of knowledge.

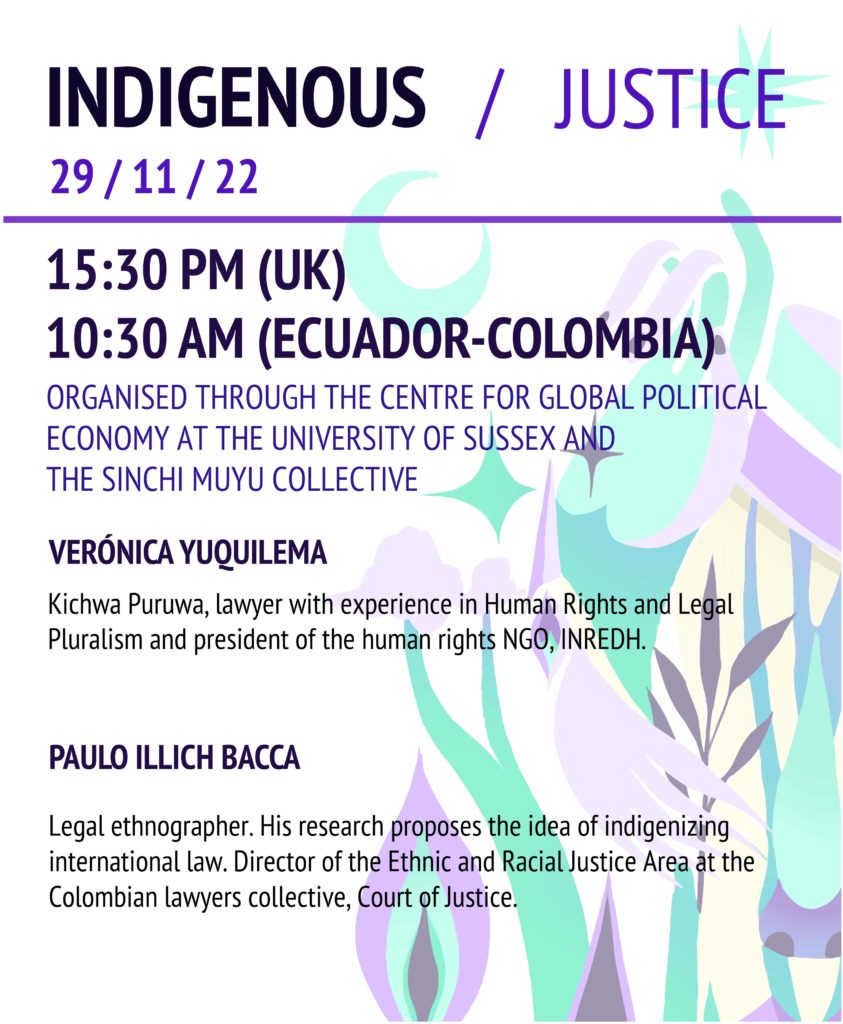

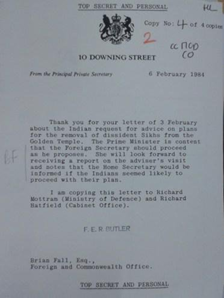

This worldview that I was presented to, adapted to the idea of property right after the total environment became the territory of modern states. The locals never considered controlling the living environment, and land trade, and pricing the access to resources, were completely unknown to them. The identity of the people my research is conducted on, was included in the protective bill that constitutionally allows the identity holder to practise a significant level of autonomy under the name of customary laws.

Perhaps reciprocally, they submit some mountainous land to the hydropower dam and military administration to contribute to national security. Engaging in this power dynamic, I was faced with the choices to position the mountain system and highland dwellers in several scenarios: perception shapes the environment, actor–network embeddedness, and assemblage of co–making of the landscape.

This raises academically–interesting questions like evaluating how land–holding statuses affect the integral health of the natural environment or resource management. On the other hand, with the fame of the world’s highest top on earth, mountaineering has grown to become an absurd extreme sport which created paid jobs for mountain dwellers, as well as intolerable trash being left to continuously disturb the ecosystem. The reduction of snow permits more months in a year to operate these businesses, yet, the singly thriving dependence on commercial climbing has considerably weakened the community’s food security and sovereignty.

What is a mountain? What is the specificity of the mountain system concerning development? Mountains are often perceived as hard objects to conquer, they are borderline between nations, sacred homes of gods, and are often represented as mysterious wasteland.

Mountains are rarely considered with the histories of the people living on them; similarly, the uncertainty around mountains cannot be fully bound by human laws. Nevertheless, that uncertainty exists and is likely to exist longer than the minds that try to comprehend it.