26 January 2017

26 January 2017

Erika Szyszczak is a Professor of Law at the University of Sussex, Barrister and ADR Mediator at Littleton Chambers, Temple and a Fellow of theUKTPO.

It is a monumental decision for a Member State to leave the European Union, not least when it will have a major impact on the economic, political and social future, not only of the exiting Member State, but also of the global trading regime. It is thus befitting that on 24 January 2017 the Supreme Court came of age by delivering one of its most important rulings, on the nature and future shape of the UK constitution. What started as a case concerning acquired rights became a wider ranging analysis of the role of the executive vis-a-vis Parliament. As befits a monumental constitutional decision, taking place in the digital age, the responses to the ruling have been prolific and focused upon the constitutional dimension to the litigation.

Robert Craig provides a very useful compilation of the commentaries.

All commentaries acknowledge that the Government “lost”. But the judgment of the Supreme Court brings some relief to Prime Minister May. All along, the government has known that a short and simple Bill can be put before Parliament and that any opposition to such a Bill has to tread a precarious path of not denying the democratic decision of the Referendum. The Supreme Court also gave comfort to the Government by confirming that it does not have to consult the devolved institutions of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales. The Supreme Court also avoided delaying the process of Brexit by not making a reference to the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU), even though aspects of Article 50 TEU are vague, for example as to the content of the agreement for a Member State to exit the EU and whether a Notice to withdraw can be revoked.

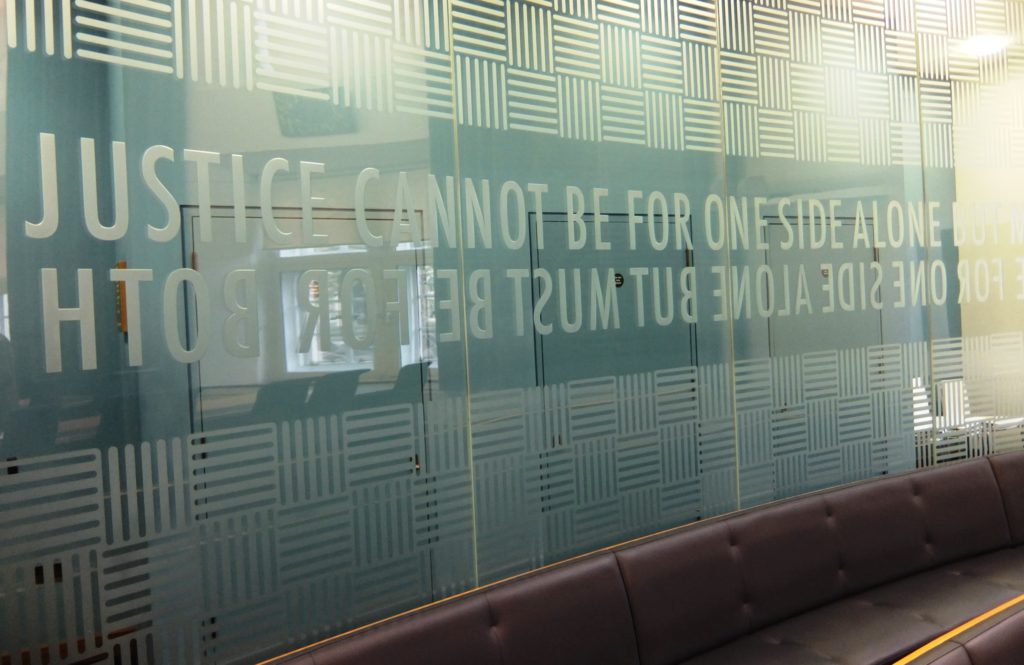

The Supreme Court (Court 2) credit: kaysgeog, FlickrTrue, there is litigation outstanding that may still raise the question of a reference to the CJEU and cast doubt upon the Government’s Brexit plans. A permission hearing in the judicial review case of Yalland and Wilding and others v Secretary of State for Exiting the EU will be heard on Friday, 3 February 2017. In that particular case, Mr Yalland and Mr Wilding contend that the UK can only leave the Single Market through the process of Article 127 of the EEA Agreement, which can itself only be triggered following Parliamentary approval. The case also addresses the question of whether the UK’s membership of the EEA will automatically cease on the UK leaving the EU.

The ruling by the Supreme Court in Miller has been universally hailed as a defeat for the UK government. But the legal challenge gave the government a much need breathing space. It was clear that, after the referendum result, there was no “Plan A” for leaving the EU. And indeed, the rest of the world appeared a hostile place to start to negotiate new trade arrangements from scratch. Remember how we were at the back of the queue for trade deals with the United States, according to President Obama? Now, President Trump appears to be tearing up the old world trade order and opening the door for bilateral global trade deals. This can only play into the hands of the UK Government.

The breathing space induced by the legal challenge has allowed the Government to consider the implications of falling back on the WTO regime as a default if trade talks with the EU fail; to talk bilaterally to most of the other EU Heads of Government; and to start to talk about trade talks with potential new partners.

At the same time the EU has struggled with national internal dissent and criticism of the various crises (and responses to such crises) it faces, such as migration and fiscal policy.

The legal question of who’s hand is on the trigger to Article 50 TEU is now of less importance than the process of the negotiations.

But the ground appears to be constantly shifting. Article 50 TEU is unclear on whether the exit agreement can be negotiated alongside a new trade agreement with the EU. To date, the government has had to be secretive. The EU’s negotiating stance remains stern, issuing a statement that the UK may not negotiate or sign any trade deals until it has withdrawn from the EU.

“Trade is an exclusive matter of the European Union. You can, of course, discuss, debate, but you can only negotiate a trade agreement after you leave the European Union,” European Commission spokesman Margaritis Schinas told reporters in Brussels.

However, these threats are arguably more political than legal. For a state departing the EU, what would be the sanctions for a breach of EU law? Even the threat of a tougher negotiating position would be self-defeating given the EU’s need to have, not only a UK trade, but also discussions on political issues, such as security co-operation in the future. Indeed the ground appears to be shifting, as Michel Barnier admitted on 25 January 2017 that the EU could not prevent trade talks between the US, India, New Zealand and Australia.

Post-referendum the electorate has clamoured for more information. Technical issues such as trade gravity models, WTO Schedules, non-tariff barriers, passporting of financial services, and so on have been discussed by a variety of commentators with varying degrees of competence. And so the press and “experts” have called for greater detail on the government’s negotiating strategy and on the nature of its desired post-Brexit settlement. Calls for a White Paper addressing the EU- Brexit and Rest-of-the-World- deals were originally dismissed by Prime Minister May. Even last week in her Lancaster House speech, the Prime Minister was emphatic that both Houses of Parliament will only be given a debate and vote on the withdrawal agreement once the Brexit negotiations ended. The Lancaster House speech was seen as the definitive framework for the Brexit deal. Then, on 25 January 2017, the PM May announced that there would be a White Paper, but, it would seem after the Bill was introduced and debated in Parliament.

There may well be other changes to the government’s stance as the Brexit process progresses.

Therefore, despite the excitement and comment on the Miller ruling, the litigation has not added greater certainty for the UK – or indeed the rest of the world – on the crucial question of what will be a “good” outcome from the Brexit negotiations and how such an outcome can be achieved.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to he original resource on the our website. We do not however, publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.