30 November 2018

L. Alan Winters CB, Professor of Economics and Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory, Dr Michael Gasiorek, a Senior Lecturer in Economics at the University of Sussex and Peter Holmes, Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex both fellows of the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

On Tuesday, the UK Government released a set of cross-Departmental estimates of the possible economic costs of different Brexit options. They were based on the Government’s own modelling, which uses a technique known as a Computable General Equilibrium modelling and is based on the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) consortium’s world model and dataset. The aim is to model (very approximately) the important linkages in an economy over a medium to long-term horizon and to assess the possible impact of changes in trade policy on the economy. (Short-term modelling, over a five year period, was simultaneously released by the Bank of England, but we do not discuss it here). The modelling approach is relatively standard, has been applied competently and honestly and produces results fairly much in line with other studies of the impact of Brexit.

This blog highlights some of the trade-related aspects of the modelling exercise and its results. As with all modelling, the main issues concern the assumptions that users input into the model rather than the model itself.

The first point is that we could have had all these results months ago. The political decision to restrict the flow of its own analysis and to rubbish/ignore those provided by other organisations substantially explains why the country has wasted so much time debating unrealistic or obviously unreasonable outcomes for Brexit; it has also contributed to making the current debate so tense. The model and most of the scenarios being modelled were clearly defined at least a year ago, and indeed modellers around the world have been producing results like the Government’s for at least 18 months.

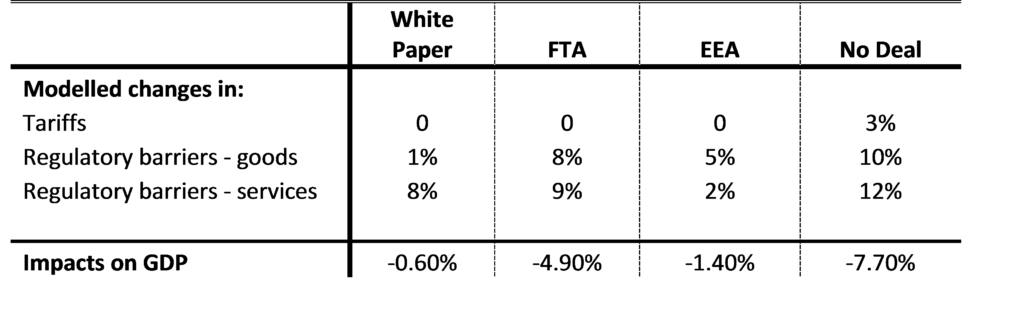

Second, the Government’s exercise contains no analysis of the backstop. Rather, it takes the White Paper from July 2018 as the Government’s current plan. Given the rejection of that plan by the European Commission, and the well-documented difficulties with the underlying proposed Facilitated Customs Arrangements (FCA) this is somewhat ‘heroic’. Three other scenarios are considered – a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) (with zero tariffs, normal customs arrangements and average regulatory barriers); a European Economic Area (EEA) style agreement which is similar to the preceding but with lower regulatory barriers for both goods and services; and a ‘No Deal’ outcome.

A summary of the key assumptions is given in the table below, and the last row shows the estimated impact on GDP.

Note: These are percentage point changes, as opposed to % changes; regulatory barriers reported as tariff-equivalents

This is the first time the Government has admitted that any Brexit will be economically costly – a giant leap forward – and it is immensely to the Civil Service’s credit that it resisted the undoubted pressures to come up with a positive view.

But politics are not completely absent, we regret to say. Two comparisons have surprised us – and most of the trade policy profession.

The first is the comparison between the White Paper (WP) scenario and the other Brexit scenarios, especially the next ‘softest’, the European Economic Area (EEA). The WP scenario assumes a tiny change in regulatory costs and barriers for trade in goods. This can be seen as being consistent with the statement in the Political Declaration that there will be no Rules of Origin between the UK and the EU. The critiques of the White Paper in July, however, suggest that this is an extremely favourable, indeed unrealistic, treatment of the WP.

The only version of the FCA that is consistent with no Rules of Origin is if the EU tariff is levied on all intermediates imports from third countries, which are then used in any good exported to the EU. This means that firms will need to have at least detailed tracking/documenting of their supply chains, if not separate production process. The Chequers plan does not eliminate the burden of origin monitoring. It simply transfers it to a bureaucratic domestic process akin to an additional layer of VAT. This increases firms’ costs, which are not explicitly modelled. Any alternative version of the FCA would require Rules of Origin between the UK and the EU, which would increase the costs of trade; moreover, not all goods would meet those rules, hence there would be some tariffs between the UK and EU. This is not modelled either.

Another element in explanation for the WP scenario’s tiny change in regulatory barriers in goods is that the analysis implicitly assumes that the “Common Rulebook” would allow more mutual recognition than does the EEA. This is highly implausible, since, while the EEA agreement covers almost the entire acquis communautaire, the White Paper plan proposes to harmonise only those rules “necessary to provide for frictionless trade at the border,” which is (a) ill-defined and designed to allow the UK to opt out of certain commitments, and (b) does not address the issue of Mutual Recognition of testing and certification.

We also note that while there is some sensitivity modelling around changes in investment, there is no modelling of the impact of uncertainty on investment, and the choices that firms and multinationals may make as to where to locate their production facilities. The UK has already seen a negative impact on foreign direct investment, and since, under the White Paper plan, negotiations with the EU on the long-term relationship will continue for several years, this uncertainty will continue.

The second comparison to note is that in comparing the status quo – essentially remaining within the EU – with any Brexit scenario, the paper assumes that the latter benefits from a swathe of Free Trade Agreements. These include rolling over every agreement that the EU has negotiated so far plus signing new agreements with the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Brunei, China, India, Mercosur, and the Gulf-Cooperation Council. These new trade agreements are assumed not only to reduce all tariffs to zero but also to reduce some non-tariff barriers (NTBs). The paper says coyly that “This is illustrative and in keeping with the Government’s ambitious free trade agenda.” Actually, it is unrealistic: the developing countries are not going to eliminate all tariffs, nor agree to serious NTB reform for the UK; the developed countries will offer little scope for regulatory convergence if the UK is adhering to a ‘common rulebook’ with the EU.

On the other hand, the estimated value of the new FTAs – an additional 0.2 per cent of GDP (rising to 0.5% in sensitivity tests) – is modest. These small effects are driven by three factors. First, the UK trades much less with these countries than with the EU. Second, existing tariffs with many of these countries are low. This is refreshingly realistic and demonstrates that signing shallow Free Trade Agreements, which would deal only with tariffs, would not provide much benefit for the UK.

Publishing estimates of the impact of Brexit is a great leap forward, as is the apparent willingness to discuss fairly openly the modelling that underpins them. Having this debate should improve the quality of analysis and the level of public understanding of the consequences of Brexit. Our complaint? That it has taken so long to happen. The current rush, public confusion and near-panic in the political system all stem from the Government’s willingness to foster public and political delusions by imposing a veil of secrecy.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.