12 February 2019

12 February 2019

Dr Michael Gasiorek is a Senior Lecturer in Economics and Julia Magntorn Garrett is a Research Officer in Economics at the University of Sussex. Both are fellows of the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

As a member of the EU, the UK is party to around 40 Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) with more than 70 countries. Over the last two years or so, the Government has stated that it intends to roll over, or more formally, ‘replicate’ these agreements. Indeed, in 2017 Liam Fox claimed that ”we’ll have up to 40 ready for one second after midnight in March 2019”. However, in recent weeks it has become clear that this is not going to happen,[1] and that at best there will only be a very small number of agreements replicated.[2] In this blog, we give some summary statistics outlining why this matters economically and which sectors are most vulnerable. We also discuss why, practically, very few agreements can be replicated by the current withdrawal date.

The EU-FTA countries accounted for 14% of UK imports of goods and 15% of UK exports over 2015-17. In addition, following the EU-Japan trade agreement that entered into force on the 1st of Feb 2019, the UK also has preferential access to Japan, which accounted for a further 1.6% of UK exports and 1.9% of UK imports. As well as Japan, six countries (Switzerland, Norway, Canada, Turkey, South Korea and South Africa) accounted for over 80% of the UK’s total goods trade with the FTA group. Economically, these are the agreements that matter the most for the UK economy.

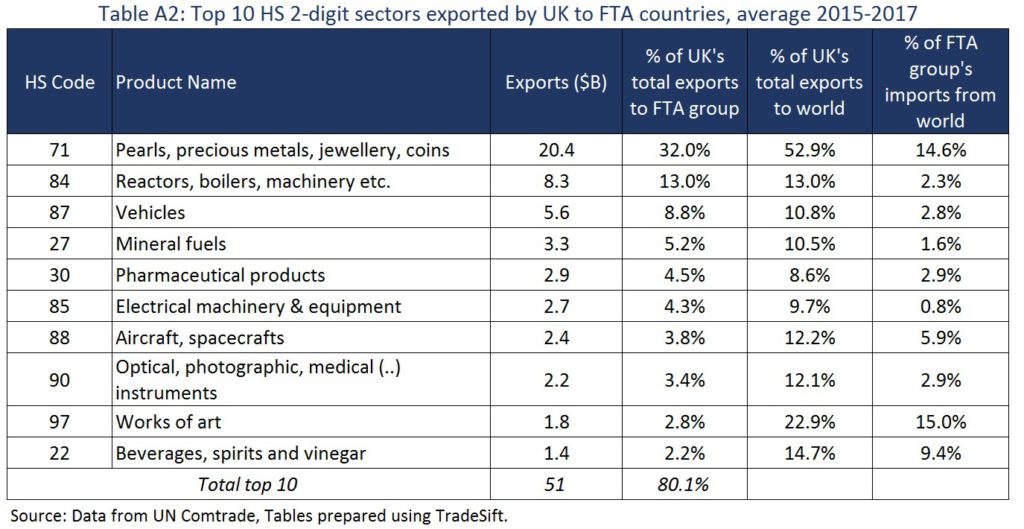

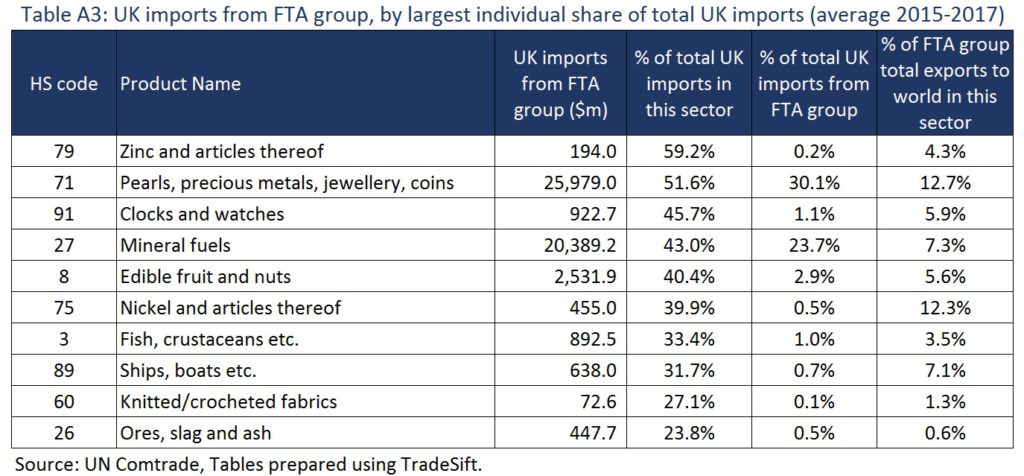

The UK’s overall trade with the EU-FTA countries is concentrated in specific products. Tables A1 and A2 in the Annex at the end provide more detail, but it is worth noting that two broad sectors: “Pearls, precious metals, jewellery”, and “mineral fuels” account for over 50% of UK imports from these countries, followed by “vehicles”, “machinery” and “pharmaceuticals” which account for another 15%. With regard to exports three sectors – “Pearls, precious metals, jewellery”, “machinery” and “vehicles” – account for more than 50% of UK exports. These are the sectors for which the EU-FTAs matter the most in terms of overall impact.

An alternative approach, however, is to consider, for each sector, how important the EU-FTA partners are as an export destination or as a source of imports (see Tables A3 and A4 in the Annex). The sector that is most reliant on imports from the EU-FTA group is “Zinc”, as nearly 60% of UK imports come from the EU-FTA partners. Other sectors with high shares range from “clocks and watches” (46%), “edible fruit and nuts” (40%), and “knitted fabrics” (27%). In a similar vein, over 65% of UK exports of “ores, slags and ash” go to the EU-FTA partners, and sectors such as “ships and boats” (30%) and “edible vegetables” (25%) also have high shares. This highlights which sectors, and the firms within them, will be more negatively impacted than others in the absence of a roll over of EU FTAs. The final column in these tables also indicates that in these sectors the importance of the UK for the EU-FTA partners is much smaller than the importance of the EU-FTA partners for the UK.

A negative impact on UK trade will arise directly from the imposition of Most Favoured Nation tariffs, as well as any reductions in market access from changes in regulatory requirements such as proving conformity assessment. While the latter are hard to assess, information on the former can be seen in Table 1 below. This considers the tariffs that UK exports would face in EU-FTA countries if there was no agreement (averaged over all those countries) and gives the number of products which would face those tariffs.[3] From this we can see that around 35% of EU-FTA countries’ imports from the UK would face tariffs of above 5%, and 65% of imports would face tariffs of less than 5%. While the latter tariffs are ‘low’, in many products and markets even small tariffs like these can eliminate firms’ profit margins.

As with most things Brexit, and as the UKTPO has highlighted before, rolling over is complicated. If there is a Withdrawal Agreement (WA) with the EU, then after March 29th, the UK will be a third country and as such no longer formally a party to these agreements. In the WA, the EU has indicated that it will “notify the other parties to these agreements that during the transition period the United Kingdom is to be treated as a Member State for the purposes of these agreements”.[4] This only applies for the transition period and formally the EU will need to issue a notification to each country, to which the country then needs to respond. This process cannot start until there is a final Withdrawal Agreement, and then the partner countries are under no obligation to agree to this request. The view of Dr Fox is that “I think that we will have full continuity, because I think it makes no sense for any country to not want to have a deal.”[5] While Dr Fox might think it makes no sense, third countries might think that have the opportunity to extract further concessions from the UK.

In the event of a no-deal Brexit, the situation becomes much more difficult, as all these agreements will need to be (re)negotiated and signed, and if this is not done by March 29th, then it looks like the UK will have to trade on WTO terms with these countries.[6] This involves Most-Favoured Nation tariffs being levied on UK exports to these countries, and the UK will need to decide on the tariffs that it levies on imports. The broad structure of tariffs that UK exporters would face can be seen in Table 1. As for UK imports, that is less clear. While for some time the UK Government had indicated it would apply the EU’s tariff structure, more recently it has emerged that alternatives are being considered.[7]

Renegotiation is likely to be complex and to depend on the long-term relationship between the UK and the EU. This is because countries may feel access to the EU market has been affected as a result of Brexit, or that the balance of interests has shifted since the initial agreement, or simply because they now feel in a stronger negotiating position. The Government is currently in discussions with the countries concerned and ‘is confident that a number of these agreements will be signed in time’, but will not be drawn on how many or which.[8] However, if this is to be achieved, then the agreements will first need to be initialled by both countries (parties), then they need to be signed. Subsequently, under the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act, 2010 (CRAG), these agreements then need to be laid in Parliament for 21 sitting days with an explanatory memorandum. Only if no objections are raised in Parliament, the UK side of the agreement is then deemed to be ratified. As of today (12th February), there remain only 29 sitting days!

It could be possible to shorten this process. Under section 22 of the CRAG, the normal procedure need not apply ”If a Minister of the Crown is of the opinion that, exceptionally, the treaty should be ratified without the requirements of that section having been met”.[9] This would be a highly unusual step as it bypasses Parliament. Importantly, depending on the partner country, any agreement would also need to go through the appropriate ratification process in that partner country. Japan and Korea, for example, have already indicated that there is insufficient time to do so between now and the end of March 2019. The UK Government is looking “to see whether there are legal mechanisms that are WTO-compatible, in order to maintain trade during what might be a legal hiatus”.[10] This amounts to a hoped-for provisional application of the treaties, where the UK hopes the partner countries will cooperate. However, for both parties, this requires that there will be “in place all implementing legislation necessary to comply with the obligations that will be provisionally applied”[11], and as the Government recognises, this is also dependent on partner countries’ constitutional arrangements, “which may impact their ability to provisionally apply international agreements in whole or in part”.[12]

The reality, therefore, is that few agreements can be replicated, or even provisionally applied by the current withdrawal date of March 2019, if nothing else because there simply is not enough time. If the UK leaves the EU without a deal in place this will not simply impact on the 50% of goods trade that the UK does with the EU, but also with the 15% of trade that the EU-FTA countries account for. One tires of saying this, but: businesses need to prepare, and in order to do so they need information. The Partnership Pack published on the 6th of February 2019 is very thin on this. The Government should provide more information on its current progress on the process of replication (for example on how many agreements have at least been initialled and on which agreements it will not be possible to replicate); what is actually planned for in the event of no deal, and on the real risks faced by UK companies in the markets they currently trade with.

[1] This has emerged from a leaked DIT briefing to businesses, as reported in the FT last week and also from evidence by Dr Fox to the International Trade Committee, 6th Feb, 2019.

[2] To date three such agreements have been laid before parliament. These are with Chile, the Eastern and Southern African States, and the Faroe Islands, another has been signed with Switzerland and an agreement in principle has been agreed with Israel.

[3] This is based on data from UNCTAD TRAINS on all HS 6-digit products imported from the UK, and the simple average Most-Favoured Nation tariffs (in 2016) for the EU-FTA group as a whole. This is an approximation since the MFN tariffs vary between the EU-FTA countries.

[4] Withdrawal Agreement, p.202

[5] Dr Fox, evidence to the International Trade Committee, 6th Feb, 2019.

[6] See: Partnership pack: preparing for changes at the UK border after a no deal EU Exit, Feb, 2019, p.53.

[7] Dr Fox, evidence to the International Trade Committee, 6th Feb, 2019

[8] Evidence given to the International Trade Committee on the 30th January by the Director for International Agreements, Foreign & Commonwealth Office, Q353-Q360. http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/international-trade-committee/the-impact-of-uk-eu-arrangements-on-wider-uk-trade-policy/oral/95846.html

[9] House of Lords Library Note I Leaving the EU: Parliament’s Role in the Process, p.11.

[10] Dr Fox, evidence to the International Trade Committee, 6th Feb, 2019.

[11] “Continuing the UK’s existing trade relationship as we leave the EU”, p.2

[12] Ibid, p.3.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.