20 May 2020

20 May 2020

L. Alan Winters CB is Professor of Economics and Director of the Observatory, Michael Gasiorek is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex and Julia Magntorn Garrett is a Research Officer in Economics at the University of Sussex. Both are Fellows of the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

On Tuesday 19th May the UK’s ‘Global Tariff’ was published. These are the tariffs that will apply on any products that the UK imports on a Most Favoured Nation (MFN) basis from the end of the transition period when the UK is no longer bound by the EU’s Common External Tariff. The published tariffs come after a public consultation on the subject was held in February this year.

This note summarises how the new tariff compares to the UK’s current MFN tariffs (which are also the rates that the UK has bound in the WTO for after the transition period) and outlines what has changed since the tariff consultation.

Under the new Global Tariff, 66% of tariff lines will see some degree of change.

Tariffs on around 2000 products have been fully eliminated, almost doubling the number of tariff-free products compared to the existing EU MFN schedule. A further 40% of tariff lines have been ‘simplified’ meaning that they have either been rounded down to the nearest standardised band, or have been converted from specific duties into simple percentages. And just under 10% of tariff lines have been converted from being expressed in € to being expressed in £ using an average exchange rate over the last 5 years. This conversion also entails some degree of simplification, as specific duties have been rounded down to the nearest £, and for two-part duties, which include both a percentage tariff and a fixed charge, the percentage component has been rounded down to standardised bands.

Table 1: Changes to the existing MFN tariff schedule

|

Change from current MFN tariff |

Number of tariff lines |

Share of tariff lines |

Simple average tariff |

|

|

Current (EU) MFN tariff |

New Global Tariff |

|||

|

No change |

3963 |

34.00% |

3.3% |

3.3% |

|

Fully liberalised |

2001 |

17.00% |

3.6% |

0.0% |

|

Simplified |

4747 |

40.10% |

6.8% |

6.0% |

|

Reduced |

12 |

0.10% |

21.0% |

10.0% |

|

Currency conversion |

1105 |

9.30% |

– |

– |

|

Total |

11828 |

100.00% |

||

|

Note: Based on raw data as published by the Department for International Trade. Tariff lines mainly defined at the 8-digit level, but some product groups are further broken down into 10-digit tariff lines. Tariff averages exclude non ad-valorem tariffs |

||||

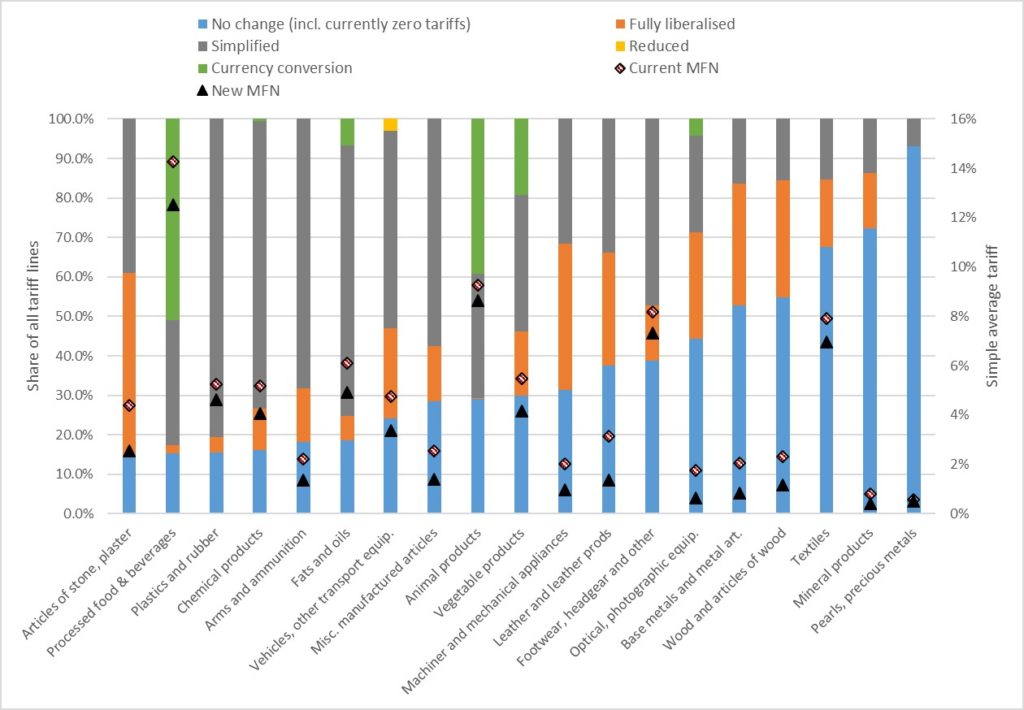

Figure 1 shows the tariff changes by product groups, as well as the simple average tariff rates under both the current MFN regime and the Global Tariff. The largest relative change (shown on the left) is for stone, plaster and cement, where around 85% of tariff lines have changed to some degree, just under half of which have been fully liberalised. This is followed by processed food products, where most of the change is due to conversion of specific duties, and plastics and rubber products and chemical products where the vast majority of tariff lines have been simplified (rounded down).

It is also interesting to see in which sectors relatively less has changed. One notable example is the textile industry, where 68% of tariff lines remain unchanged, most of which maintain tariffs of 8% or 12%. Indeed, the Government states that tariffs on textiles (as well as products such as bananas, raw cane sugar and certain types of fish) have been retained in order to avoid preference erosion for developing countries.

Finally, figure 1 also shows that the impact on average tariff rates is modest. The sectors with the largest changes are articles of stone, and leather products, which both see declines in average tariff rates of around 1.8 percentage points respectively. It is particularly notable that in some sectors, such as plastics and rubber, chemical products as well as fats and oils, the average tariff rates stay almost unchanged despite a large number of products being simplified (rounded down).

The tariff averages given in figure 1 exclude any non ad-valorem tariffs (i.e. tariffs which are not expressed in simple percentages).[1] These figures therefore do not reflect any changes to average tariffs that arise due to currency conversions, but it is worth noting that the conversions have been made based on an average exchange rate over the past 5 years, of 0.83687. Given that today’s exchange rate is 0.89 this implies a de facto 6% ‘liberalisation’ compared with today’s rates.

Figure 1: Changes from current MFN schedule, by product group

Note: Based on 8-digit level of aggregation (although some tariff lines have been broken down further into 10-digit categories). Product groups ‘wood pulp’ and ‘works of art’ have been excluded as all tariffs under these groups are already zero. Averages exclude any non-ad valorem tariffs.

The tariff changes would increase the share of imports that can be imported duty-free from countries currently trading on MFN terms. Under the Global Tariff, around 70% of the UK’s imports from ‘MFN countries’ would be duty-free compared with around 52% currently. However, the Global Tariff is far less liberal than the UK’s (now superseded) ‘No deal’ tariffs that were published in October last year, which would have seen tariffs eliminated on around 95% of imports from ‘MFN countries’.

If the UK and the EU do not reach a trade deal by the end of the transition period, the Global Tariff will apply also to imports from the EU. In this scenario, only around 44% of imports from the EU would be tariff free, compared with 100% currently. This is a higher share than if the current MFN tariff schedule was applied on EU imports, but is a much smaller share than it would have been under the ‘No deal’ tariffs.

Table 2: Percentage of the value of UK imports facing 0% tariffs

|

Reporter group |

Current (EU) MFN schedule |

UK Global Tariff |

UK ‘No deal’ tariff |

|

‘MFN’ countries |

51.5% |

70.3% |

95.6% |

|

EU |

33.1% |

44.2% |

81.3% |

|

Note: Based on the 8-digit level of aggregation. Trade data sourced from HMRC’s Overseas Trade Statistics for 2018. ‘MFN’ countries are those countries which currently trade with the UK on a Most Favoured Nation basis. |

|||

The tariff consultation earlier this year contained 5 broad proposals:

All of these figure to some extent in the new Global Tariff:

1. The consultation defined nuisance tariffs as 2.5% or less and would have eliminated around 900 tariffs. In the Global Tariff, the threshold has been set at tariffs less than 2%, which eliminates just under 500 tariffs.

2. The Global Tariff rounds down (simplifies) in bands of 2% rather than 2.5% for tariffs below 20%. This seems a minor change, but it matters for a broad range of textile products which currently face tariffs of 12%. Under the consultation proposal these tariffs would have come down to 10%, whereas in the final version they remain at 12%.

As table 1 showed, around 40% of all tariff lines are simplified. The vast majority see changes of 0.5 percentage points or less, whereas only around 40 tariff lines change by more than 2 percentage points. The mean change due to simplification is -0.87 percentage points.

3. One of the larger divergences from the consultation proposal concerns agricultural tariffs. In the consultation, DIT proposed that agricultural products that face specific duties or two-part duties, should be simplified into simple percentages. While some agricultural tariffs have been simplified, overall this proposal has largely not been carried out in the final version. Only around 10% of the non-ad valorem duties have been simplified. The simplification includes removing the EU’s Entry Price System and Meursing System, as well as setting a single rate for tariffs which previously varied seasonally, or which applied a minimum and maximum tariff level.

4. In the consultation, the DIT proposed that tariffs on intermediate inputs going into UK production should be eliminated to support UK producers. The consultation document suggested three different non-exhaustive lists that could be used to classify goods as intermediates, the most comprehensive of which, the UN’s Broad Economic Categories (BEC), classifies over half of all products as intermediates. While some intermediate products have indeed been liberalised, about half of all products classified in the BEC as intermediates still have positive tariffs.

5. In the tariff consultation, the UKTPO and a number of other respondents suggested liberalising tariffs on environmental goods. This has been taken on board, and the Government has reduced tariffs on around 100 products which it deems to be ‘green’ goods, including items such as turbine parts, gas turbines and waste containers. Looking at the provisional list drawn up during negotiations for the Environmental Goods Agreement, the Government has fully liberalised around 44% of the products on this list that were not already zero. Tariffs on a further 24% of products on this list have been reduced, albeit by a relatively small amount (less than 3 percentage points) and only 5 products on the list have not seen any form of liberalisation.

6. Finally, the Government has proceeded with its proposal to eliminate tariffs on products where UK domestic production is zero, or very low. It does not specify how many tariff lines this affects, but lists items such as textile fibres, cotton and wood among the selected product groups. Nevertheless, the government recognises the need to retain certain tariffs to avoid preference erosion for developing countries, choosing to maintain tariffs on, for example, pineapples and crude coconut oil.

In a later blog we will analyse more thoroughly what these changes mean for UK’s trade and trade policy, but to summarise factually: the tariffs on over half of products have changed, but the weighted average tariff on goods imported from ‘MFN’ countries has fallen only from 2.1% to 1.5% (excluding non ad-valorem tariffs). Given that any difference between the UK and EU tariffs may create administrative problems, for example for rules of origin on trade with the EU and on the Northern Irish border, there is room to ask whether this has been a net gain.

[1] Detailed analysis is needed to evaluate how much each of the over 1,000 specific tariff has been changed due to the currency conversion and rounding down. In this analysis we have been unable to do so, but we endeavor to do so in the near future.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Very helpful summary. Many thanks.

Thanks for this very helpful analysis as it addresses a point which was puzzling me, namely why tariffs are being maintained on products like pineapples which the UK doesn’t produce. Your explanation is that this is being done to protect exports from developing countries from competition, since they will be entitled to enter at lower preferential rates, whereas competing products from elsewhere will be subject to the higher duties in the new Global Tariff. That explanation makes sense to me. But I am still puzzled by some of the tariffs on other products which the UK doesn’t grow – for example, fresh sweet oranges, fresh navel oranges and fresh white oranges seem to have a tariff of 10% between November and April, but which lowers to 2% between May and October. I think I’m right in saying that Nov-Apr is the EU orange harvesting season – in which case, isn’t the 10% seasonal tariff essentially designed to hit EU orange growers? Or is it that in the Nov-Apr period, more oranges generally are available so the price is lower – and therefore the higher 10% tariff is needed to ensure that exports from developing countries remain competitive in the UK market? Many thanks in advance if you are able to shed any light on this.

Thanks Jon, this is a really interesting question.

There are three suppliers from which the UK imports the vast majority of its oranges: the EU (Spain mainly) (41%), South Africa (28%) and Egypt (20%). There are no developing countries trading on the basis of GSP/EBA that export any significant volumes of oranges to the UK, so protecting developing countries’ preference margins doesn’t seem to be a reason for the tariffs here.

As you suggested the majority (about 65%) of the imports from the EU come in during November to April (the period with the higher tariffs). This is about the same for Egypt, but for South Africa almost all oranges are imported in May to October. As you said, this suggest that the tariffs might be strategic, to be used as a bargaining chip in the negotiations with the EU. The UK is also still trying to agree a continuity agreement with Egypt, to replace the EU’s Association Agreement, so maybe there’s also a strategic case there, although the EU-Egypt AA mainly covers industrial goods and doesn’t fully liberalise trade in oranges, but includes a TRQ for trade over the period Dec-May.

Thank you very much for this really informative reply. It’s interesting that there might be an angle relating to the Egypt agreement as well. I also wondered if there might be a strategic case in relation to the trade talks with the US, since it appears the US is a major orange producer. Maybe the idea is that, if there is no deal with the EU, a deal with the US covering oranges could prompt UK retailers to look to US producers instead of EU ones in order to avoid the 10% seasonal tariff. But if UK retailers can’t switch to cheaper supplies, presumably UK consumers of oranges will pay the price of no deal with the EU (unless of course the UK government reverts to something like its interim no deal tariff schedule from last year).

I think this is absolutely first class, and very helpful indeed, but have one question. It says the f/x changes were done using a recent 5-year average, but base periods are normally 3-year – as with the TRQ split – or occasionally a 5- year Olympic average. So I was wondering why a 5-year average was used in this case?

I’m glad that you found the blog useful!

There is not much information on why a five year average was used, but it seems to have to do with the UK’s WTO obligations. The Government’s policy document says: “The exchange rate is the average rate of the last five years. This decision was taken separately to the consultation, factoring in the UK’s legal commitments at the WTO.”

(see p. 9 of this doc: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/885943/Public_consultation_on_the_UK_Global_Tariff_government_response.pdf)

[…] Britain plans to eliminate or round down the tariff charged on more than half of some 12,000 products, but most of the changes will be mere tweaks. Researchers at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, based at the University of Sussex, note that the weighted average tariff charged on goods imported from “most favoured nations” will fall only from 2.1 per cent to 1.5 per cent. […]

[…] Britain plans to eliminate or round down the tariff charged on more than half of some 12,000 products, but most of the changes will be mere tweaks. Researchers at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, based at the University of Sussex, note that the weighted average tariff charged on goods imported from “most favoured nations” will fall only from 2.1 per cent to 1.5 per cent. […]

[…] Britain plans to eliminate or round down the tariff charged on more than half of some 12,000 products, but most of the changes will be mere tweaks. Researchers at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, based at the University of Sussex, note that the weighted average tariff charged on goods imported from “most favoured nations” will fall only from 2.1 per cent to 1.5 per cent. […]

[…] Britain plans to eliminate or round down the tariff charged on more than half of some 12,000 products, but most of the changes will be mere tweaks. Researchers at the UK Trade Policy Observatory, based at the University of Sussex, note that the weighted average tariff charged on goods imported from “most favoured nations” will fall only from 2.1 per cent to 1.5 per cent. […]

Thank you for this very useful summary. I declare an interest (www.acpsugar.org). What do you think about the fact that only one product has been subjected to an Autonomous Tariff Quota, that product being raw cane sugar for refining (with two tariff headings depending on quality of the product)? Could the existence of this UK raw sugar ATQ undermine the the EU27 single market if the UK/EU agrees a zero-for-zero free trade agreement?

[…] which are expected to apply from January 2021, have also only recently been published. As the Analysis company UK Trade Policy Observatory has calculated that the UK will only allow 44.2 percent of EU imports duty-free if the UK and the […]

A helpful overview – but you seem to have avoided some key issues. Please forgive my directness as it looks impolite. It isn’t intended to be. I’m just curious on two issues.

1. You could have explored if this tariff schedule gives countries an incentive to pocket the reduced and removed tariffs whilst acting as a disincentive for them to reciprocate? Thus:

It allows, “…Around 70% of the UK’s imports from ‘MFN countries’ [to be] duty-free compared with around 52% currently” and, “around 44% of imports from the EU would be tariff free.”

i. Does this mean that 44% of EU goods enter UK supply chain without tariffs whilst not reciprocating? No wonder they are in no hurry over trade talks! There would be every incentive to avoid UK suppliers in its supply chain (more expensive due to its tariffs) but that’s not the same in reverse. No quid pro quo.

ii. Countries have no need to negotiate with the UK when they largely get 70% of their goods into the UK for free. It’s Christmas every day!

iii. Similarly, if the UK is applying zero tariffs largely when it “has zero or limited domestic production” then why would a country, say, selling oranges, want to give UK industrial products a zero tariff when it gets into the UK for free? Meanwhile, the EU can negotiate increased tariff free quotas for favourable terms for its industrials.

You may have addressed issues like this elsewhere. It’s certainly helpful that you have collated the data – but exploring arguments as to what does this mean….would have made it stronger.

2. How can this body call itself independent when you lobbied for zero tariffs on environmental goods? Don’t get me wrong, the aim is a good one. But you show yourselves to be a player in the game rather than an observer. That’s fine – but you should set out your lobbying objectives so that readers know that you are independent but for……..

Thank you,

Paul

If removal of tariffs is not reciprocated, the losers are those in the country which does not reciprocate. It’s their funeral.

What is the point of all these tariffs? The system causes delays, cost money to administer and puts up prices. This in turn pushes up government expenditure on indexed benefits.

In your updated review, I would be interested to understand how you think the UKGT will affect those products that were subject to the recent imposition of tariffs from the EU, in the Airbus ruling. It sets an interesting precedent on the UK’s view on “tariff free” trade, considering the demonstrated move to a more regulated version with the UKGT than the “No Deal” tariff. Especially as the USA is seen as a key market in many of Truss’ rhetoric.

A silly example, but I collect pinball machines and they were caught up in the EU/USA Airbus tariff situation. At present they are taking a 25% tariff on all imports, dropping to 0% under the UKGT. There is no mention of it on the two most prevelant sites that sell these machines and their parts in the UK. (https://www.pinball.co.uk/ and https://pinballbazaar.co.uk/) – it would be a good analysis to see how many of these recently imposed with the USA – EU tariff are now out of scope with the UKGT.

The recent publication of the EU trade agreement has a very stringent section it would seem of “Country of Origin”, to counteract this. It would be interesting to know of these recently imposed tariffs, which are now outside of scope with the UKGT. Given the UK has an interest in this case.

[…] Reference: https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2020/05/20/new-tariff-on-the-block-what-is-in-the-uks-global-tariff […]