8 July 2021

L. Alan Winters is Professor of Economics and Founding Director of the UKTPO. Guillermo Larbalestier is Research Assistant in International Trade at the University of Sussex and Fellow of the UKTPO.

On 1st June 2021, as part of its post-Brexit trade architecture, the UK Government launched the Trade Remedies Authority (TRA). On 11th June the TRA recommended the extension of only some of the quotas and tariffs on steel imports that the UK had inherited from the EU. On 30th June, one day before these measures were due to expire, the Government rejected the TRA’s recommendation and extended the policies on several categories of steel for which the TRA had recommended the revocation. It also announced a review to check whether the TRA was ‘fit for purpose’. What was going on? And does it matter?

The TRA was created by the Trade Act, 2021. Its principal task is to advise the Government on so-called Trade Remedies – the imposition of temporary restrictions on imports in the face of unfair trade (resulting from dumping or subsidies) or unforeseen shocks (safeguards) which cause injury to UK producers. It does so in the light of proven facts about trade and production conditions, having sought evidence from interested parties (which it checks for credibility) and having made an objective balancing of the various interests – it is the ‘computor’ in the title of this blog. The Government may accept or reject the recommendation as whole, but not amend it; and if it rejects it, it must explain why to Parliament.

Safeguard restrictions are permitted in the WTO on condition that they:

Safeguards can comprise both quotas and import duties, including tariff rate quotas (TRQs) which impose tariffs, but exempt a given quantity of imports from them. TRQs are the tools used in this case of steel imports. The TRA’s regulations, mostly embodied in the Taxation (Cross Border Trade) Act, 2018, are broadly in line with WTO rules and practices.

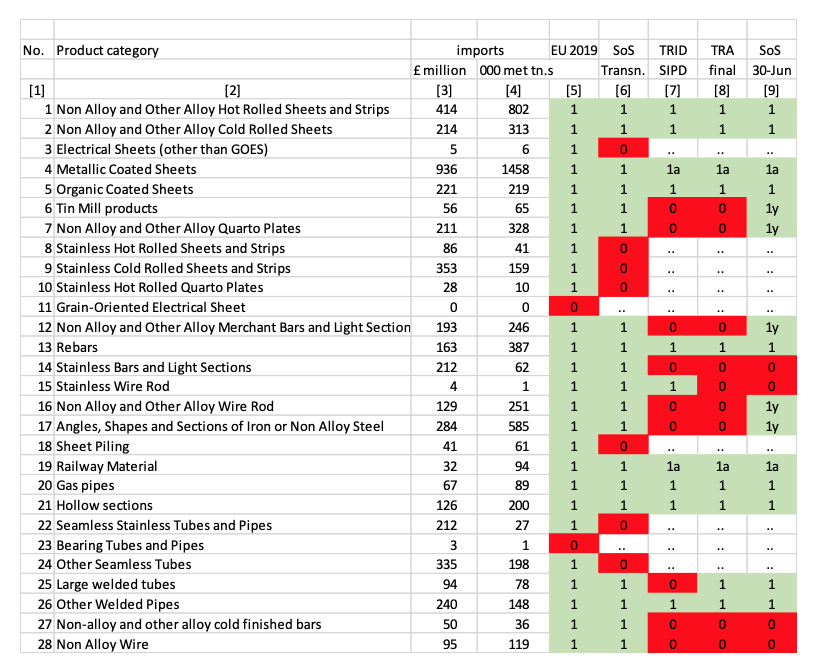

In March 2018, President Trump introduced 25% tariffs on US imports of steel and aluminium. One reaction to this was that other countries, including the EU, introduced safeguards on steel because, or in order to forestall, the exports excluded from the USA being diverted to their markets. This was no surprise: steel has always been subject to such temporary interventions. The EU investigated 28 categories of steel (covering over 300 8-digit product codes) and introduced TRQs on 26 of them definitively on 31st January 2019 – the outcome is summarised in Table 1 (column 5). The UK inherited these TRQs and at the end of the transition period on 1st January 2021 decided to maintain 20 of them, the remaining 6 being deemed to have no UK production and hence no case for safeguard.

In October 2020, the Secretary of State for International Trade, Elizabeth Truss, requested the precursor of the TRA (the Trade Remedies Investigations Directorate, TRID) to investigate whether the inherited safeguards were appropriate (and implicitly legal) for the UK to extend beyond 30th June 2021.[1] They did so by examining whether the UK had experienced a significant increase in imports during the investigation period used by the EU (2013-17).[2] It also investigated more recent data to check whether imports were likely to surge if the TRQs were abolished and the extent of injury if they did.

The TRID/TRA collected submissions from many parties – largely from both upstream and downstream firms and business associations and traders. It issued a Statement of Intended Preliminary Decision (SIPD) on 19th May 2021 and collected further representations quickly thereafter. These altered their conclusions somewhat and they published their analysis and final recommendation on 11th June 2021. The documents are not an exciting read even for trade wonks, but they clearly convey the serious and thorough nature of the investigation including the evidence used and the analysis it supported.

The TRA slightly altered the classification of the groups and made recommendations on 23 categories.[3] Of these, they recommended extending the safeguard measures for 11 categories in their current form for three years with a small growth in the permitted quotas. The TRA identified unforeseen import growth, the likelihood of an import surge and sectoral injury if the TRQs were abolished. For 12 categories, on the other hand, the TRA recommended revoking the TRQs. Of the latter:

On 30th June 2021, the Secretary of State rejected the TRA’s recommendation and replaced it with her own partly underpinned by a bespoke Statutory Instrument made at 5:40pm and coming into force at 6:00pm on that day! Two policy notices embody her decision:

1) The first, ostensibly in accordance with TRA regulations, extends the 11 TRQs in the terms proposed by the TRA;

2) The second, requiring bespoke legislation, extended TRQs for one year on 5 product categories: for 3 the TRA had recorded no overall increase in imports over 2013-17; for 1 it had identified temporary increases in 2015 and 2016 but a return to normal in 2017, and for 1 it found no useable evidence on UK production and so an injury determination could not be made.

The third element of the decision was to accept the TRA‘s recommendation to let the TRQs on 7 categories expire on 1st July 2021. The evolution of the TRQs from the EU investigation to the current outcome is sketched in Table 1.

The Secretary of State’s ‘pick and mix’ approach is contrary to the TRA Regulation’s Article 52(1), which requires that ‘Where the TRA makes a recommendation …., the Secretary of State must accept or reject that recommendation’ and the fact that the TRA made just one recommendation.[4] The ‘all or nothing’ requirement is designed to try to oblige the Government to recognise the need for balance and to decide matters on principle rather than on the political expediency of favouring some interests over others.

Temporary TRQs on imports of five categories of steel are not a huge issue per se. But the issue is important for what it says about the UK Government’s attitude to rules and trade. The Government preferred ad hoc political decision-making to anything resembling an objective decision based on legislated procedures:

The structures for administrative protection such as safeguards and antidumping actions are far from perfect. They are bureaucratic, costly and disadvantage small firms and consumers. Large firms and those that would gain a great deal from protection can afford the resources to operate the system in their favour by collecting and presenting evidence and employing very smart lawyers. Small firms lack resources and individual consumers lack the incentive to oppose any particular tariff because it has only a small effect on their budgets. But policies add up over sectors and there are millions of consumers, so in the end they are greatly under-represented in decisions to introduce trade restrictions relative to the aggregate harm they suffer from reducing imports.

My good friend and colleague the late Mike Finger was a fierce critic of administered protection, but he eventually concluded that it does have one virtue. Analysing policy-making in Peru and Argentina, he concluded that, by codifying and making open the process of making one-off protection decisions, these procedures help to avoid political ad hocery and its eventual descent into favouritism, clientelism and chaos. The TRA was a step in the right direction, and in one swoop, Ms Truss has jumped straight back into the fire.

Notes:

Notes:

Column explanations:

[1] product group numbers from EU 2019

[2] category description

[3] UK imports, 2019, £ million

[4] UK imports, weight, thousand metric tonnes

[5] outcome of EU investigation REGULATION (EU) 2019/159

[6] UK Secretary of State’s Transition decisions, 2020

[7] TRID’s Statement of Intended Preliminary Decision, 19th May 2021

[8] TRA’s Recommendation to the Secretary of State (TF0006), 11 June 2021

[9] Secretary of State’s TRADE REMEDIES Notices No.s 1 and 2, 30 June 2021

Explanation of entries:

1 (shaded green) TRQ recommended/implemented; 1a TRQ recommended but on a slightly reduced set of product codes within the category; 1y TRQ implemented for one year

0 (shaded red) TRQ investigated but not recommended/implemented

.. (shaded white) TRQ not investigated because ruled out at an earlier stage

[1] With its independent trade policy, these decisions had to be based on UK data alone.

[2] The EU investigated imports into the EU. It was necessary to go back to the original period because the question was to extend the measures, not to introduce new ones.

[3] Relative to the EU exercise, the TRA disaggregated categories 4,19, 25 and 28 – see below for definitions.

[4] The fact that emergency bespoke legislation was required seems to confirm this. The EU makes overturning advice on trade remedies more demanding politically than merely introducing ad hoc legislation in a hurry.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

The Safeguards Agreement not only sets out the conditions that must apply for safeguard action to be compliant but also the procedural requirement that there is an investigation by the competent body. Implicitly this suggests that action is permissible only if shown to be needed by that investigation. The member state can, of course, decide not to take the action proposed by the investigating body but it makes that requirement that there be an investigation pointless if the member state can take action not proposed by the investigating authority. Presumably Miss Truss was made aware of this but she may have calculated that, even if the WTO dispute settlement system was working, it would take a long time for this obvious conclusion to be reached. But WTO members are required to notify new safeguard measures and, assuming that this counts as a new measure because its predecessor was an EU meansure not a UK measure, at the very least, the UK is facing an uncomfortable session in the WTO Council when other members query the factual and procedural requirements that this measure fails to have.