31 March 2023

31 March 2023

Minako Morita-Jaeger is Policy Research Fellow at the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Senior Research Fellow in International Trade in the Department of Economics, University of Sussex

On 31st March, the UK announced an agreement in principle to become a member of the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Politically, this is a positive step, especially as the Prime Minister can sell accession as a tangible achievement of the UK’s independent trade policy. But what is the real value of joining the CPTPP, and what are the key issues to examine?

A big geopolitical strategy gain with a small economic gain

Today, international trade policy is increasingly geopolitically volatile. Within that context, in the Indo-Pacific region, there are three significant plurilateral configurations.[1] One is the CPTPP, which is a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) of like-minded countries promoting an open and rules-based trading system. The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP)[2] is a more development-friendly and shallower FTA in comparison to the CPTPP which includes China.[3] The Indo-Pacific Economic Forum (IPEF) is not an FTA but a policy forum negotiating trade-related rules.[4] It is led by the US where a strong motivation is the containment of China.

For the UK, the significance of the CPTPP should thus be seen in the context of a wider foreign geopolitical strategy beyond trade. In the UK’s latest Integrated Review 2023,[5] the Government reaffirmed the importance of the ‘Indo-Pacific tilt’, for which the CPTPP provides a core policy framework. The CPTPP could enable the UK to enhance strategic ties with like-minded countries to protect a free and open Indo-Pacific region.

Yet, the economic value for the UK is likely to be small. On the face of it, the CPTPP looks to create new opportunities for the UK given the size of the market (11% of the world’s GDP, US$14.3 trillion; 14% of world exports and imports of goods and services, US$7.5 trillion). However, the predicted long-term economic gains for the UK are but a possible 0.08% increase in GDP.[6] The UK already has bilateral FTAs with nine CPTPP members out of eleven,[7] including ‘comprehensive and deep’ bilateral FTAs with its top four CPTPP trade partners (Japan, Canada, Singapore, Australia)[8].

What price will the UK pay?

While joining the CPTPP may be a geopolitical strategic gain, it is important to be mindful of the economic and social consequences. These will depend on the final agreement. Consider two examples.

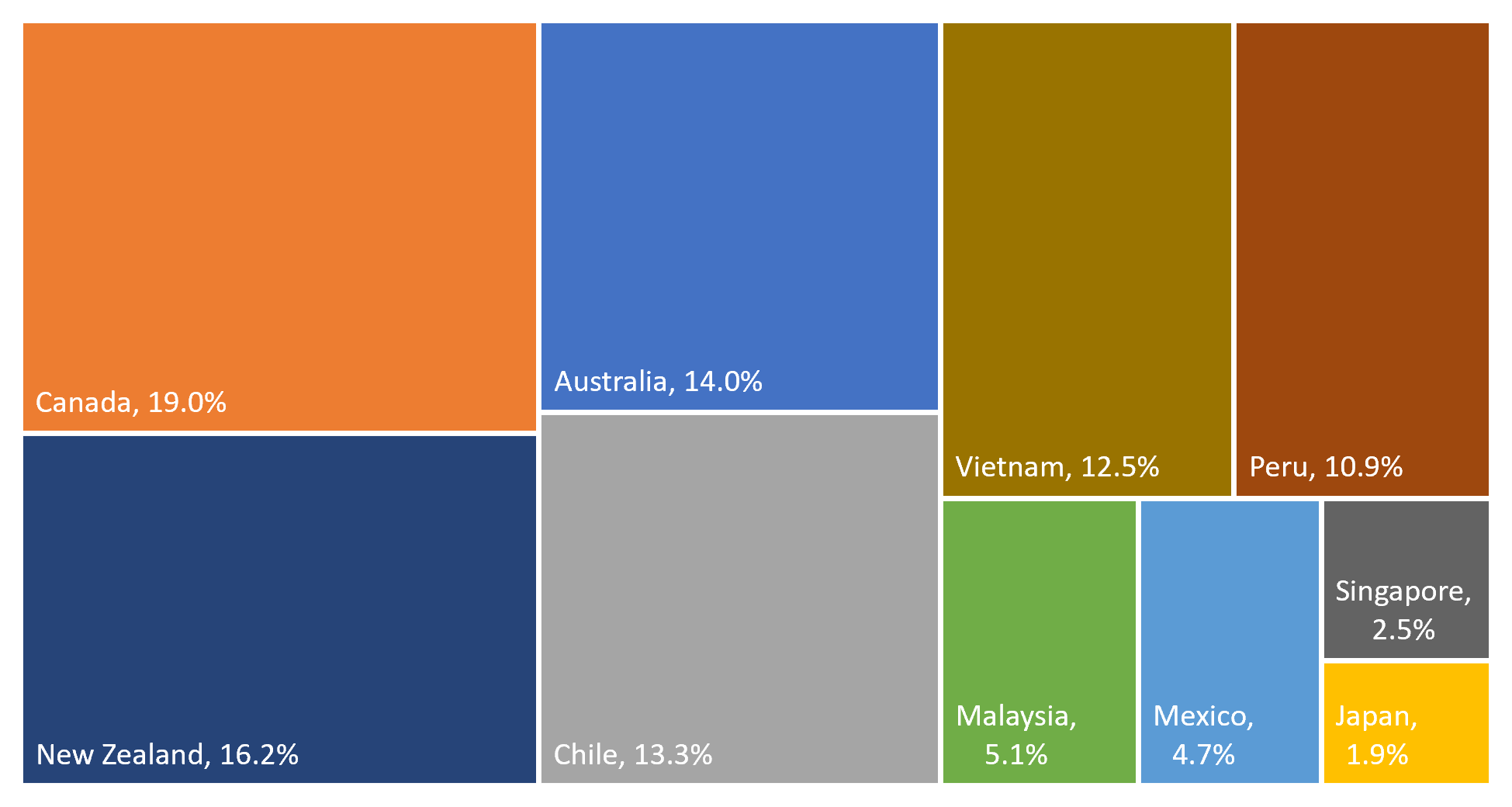

Take first the UK’s agricultural market access concessions. The CPTPP has its own schedules of market access commitments which in principle apply to all members, hence the UK cannot differentiate its commitments by country. Canada is the largest CPTPP agricultural exporter to the UK (Fig.1). A critical issue is whether the UK grants the same levels of market access as it already has for Australia and New Zealand under its bilateral FTAs to all CPTPP members. Depending on the arrangements, an increase in imports of some products (e.g. beef, sheep meat and dairy products) may impact on UK agriculture. [9]

Figure 1: Agriculture & Agri-food exports from the CPTPP members to the UK (£) -2021

Data source: HMRC Overseas Trade Statistics, 2021.

Note: Shares are out of CPTPP total exports of agriculture and agri-food products to the UK. Agriculture and agri-food products are defined as those under HS Chapters 01-24.

Second, consider regulatory policy constraints. The UK has different regulatory regimes and norms in comparison to Indo-Pacific countries, however, accession requires acceptance of existing CPTPP rules. UK stakeholders have expressed concerns that some provisions may create economic, legal, societal and technical problems both at the domestic level and for the UK’s relationship with the EU.[10] Examples include free cross-border data flow (CPTPP Art. 14.18) and its potential impacts on data privacy and the EU’s data adequacy decision;[11] incompatibility between the CPTPP intellectual property provisions (CPTPP Art. 18.83) and the UK’s membership of the European Patent Convention; the UK’s ability to maintain the precautionary principle for agriculture and food standards (CPTPP Art. 7.9 (2))[12] and animal welfare standards; and Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) mechanisms (CPTPP Chapter 9: Section 9B) and its regulatory chilling effects in the areas of environment, labour and health.[13]

In the medium to longer term, the economic and political trade-offs will also depend on the future evolution of the CPTPP, notably regarding China’s possible accession, and the evolution of other fora such as RCEP and IPEF, and the UK’s response to these.[14]

[1] Wilkins, T. and Kim, J. (2022) ‘Adoption, accommodation or opposition? – regional powers respond to American-led Indo-Pacific strategy’, Pacific review, 35(3), pp. 415–445. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2020.1825516

[2] RCEP members are: ASEAN members (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam) plus Australia, China, Japan, New Zealand and South Korea.

[3] Hamanaka, S. (2016). TPP versus RCEP: Control of membership and agenda setting, Journal of East Asian Economic Integration Vol. 18, No. 2 (June 2014) 163-186.

[4] The current IPEF members are: Australia, Brunei, Fiji, India, Indonesia, Japan, South Korea, Malaysia, New Zealand, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

[5] HM Government (2023). Integrated Review Refresh 2023. Responding to a more contested and volatile world; Integrated Review Refresh 2023: Responding to a more contested and volatile world – GOV.UK (www.gov.uk)

[6] DIT (2021). UK Accession to CPTPP: The UK’s Strategic Approach. UK Accession to CPTPP: The UK’s Strategic Approach (publishing.service.gov.uk).

[7] Note that the UK does not have a bilateral FTA with Brunei and Malaysia. The UK-Australia FTA and the UK-NZ FTA have not entered into force.

[8] Trade with these four countries accounts for 81% in goods exports, 66% goods imports, 86% services exports, 90% services imports. See the Written evidence from the UKTPO for the International Trade Committee Inquiry for the CPTPP. https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/111176/pdf/

[9] The UK agricultural sector expressed concerns on tariff-free arrangements under tariff-related quotas in these products and the safeguard system under the UK-Australia FTA and the UK-NZ FTAs. See (https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/106220/html/) and https://committees.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/23830/pdf/.

[10] Debates in detail are available at the House of Commons, International Trade Committee website: UK trade negotiations: CPTPP accession – Committees – UK Parliament and House of Lords, International Agreements Committee website: Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) – Committees – UK Parliament.

[11] Morita-Jaeger, M. (2021). Accessing CPTPP without a national digital regulatory strategy? Hard policy challenges for the UK, UKTPO Briefing Paper 6:; Accessing CPTPP without a national digital regulatory strategy? Hard policy challenges for the UK « UK Trade Policy Observatory (sussex.ac.uk).

[12] Lydgate, E. (2021). CPTPP and agri-food regulation: Crossing the EU-exit rubicon?, UKTPO Briefing Paper 60: CPTPP and agri-food regulation: Crossing the EU-exit rubicon? « UK Trade Policy Observatory (sussex.ac.uk).

[13] ‘Regulatory chill’ means that ISDS may have adverse effects on governments’ willingness to regulate in the public interests as governments fear potential liability. There are many studies, such as Tienhaara, K. (2018). Regulatory Chill in a Warming World: The Threat to Climate Policy Posed by Investor-State Dispute Settlement. Transnational Environmental Law, 7(2), 229-250. Doi:10.1017/S2047102517000309.

[14] Morita-Jaeger, M. and Larbalestier, G. (2021). The economics and politics of China’s accession to the CPTPP, UKTPO blog: CPTPP china « Search Results « UK Trade Policy Observatory (sussex.ac.uk). Also see a coming UKTPO Briefing Paper on the future evolution of the CPTPP and the UK.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

America may rejoin CPTPP!!

CAPX wrote an article about how the UK membership of CPTPP is worth alot more than 0.08% of GDP.

http://www.chattamhouse.org article Why Joining The CPTPP is A Smart Move For The UK.