Customs and Trade Facilitation

Mutual Recognition of Testing and Certification

The Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the UK and the EU has now been agreed and came into force on the 1st January 2021. The TCA is over 1200 pages long, 800 of which are comprised of annexes to the main body of the agreement. It covers a wide range of issues including institutional arrangements, trade in goods and services, travel, transport, fisheries, social security coordination, law enforcement and judicial cooperation, union programmes and dispute settlement.

Following the Agreement, we have produced three companion Briefing Papers in parallel. This Briefing Paper, No 52, focusses on the provisions on trade in goods. The second in this mini-series, Briefing Paper No.53, assesses the TCA with regard to trade in services; and the third, Briefing Paper no.54, focuses on Governance, subsidies and the level playing field provisions. In each case, we identify what has (or has not) been agreed, assess the significance of the respective elements of the agreement, and point to some of the possible future implications. Needless to say, that this is a preliminary assessment and more work on some of the details will be needed.

The good news is that the TCA allows for the elimination of all tariffs and quotas between the UK and the EU – providing that firms can prove they meet the underlying rules of origin, and providing that neither party subsequently levies any anti-dumping duties, or countervailing duties, or any ‘rebalancing’ measures.[1] See below for a more detailed discussion of some of the bureaucracy and complexities associated with rules of origin. For many goods, this will mean that there should be no tariffs levied on bilateral trade, although they will be subject to customs declarations and inspections. This is an important outcome which will certainly help to reduce the losses from leaving the EU. Note that special provisions, under the Northern Ireland Protocol of the Withdrawal Agreement apply to trade between the EU and Northern Ireland, and between Northern Ireland and Great Britain.

With regard to tariffs, therefore, and providing the rules of origin can be met, the UK maintains the same level of tariff-free access for goods into the EU market as it did before and vice versa. However, there is one further difference: on a large number of goods the UK’s Most Favoured Nation (MFN) tariff, which came into force on January 1st, is lower than the tariff that was levied up to that date (the EU’s common external tariff). For just over 2000 tariff lines, the UK has eliminated the tariffs, for which the simple average was 3.6%. For 4747 tariff lines the UK has marginally lowered the import tariff in a process of simplification, such that for these products the simple average tariff has been reduced from 6.8% to 6%.[2] Under the Global Tariff, around 70% of the UK’s imports from ‘MFN countries’ would be duty-free compared with around 52% under the EU’s common external tariff. The MFN tariff is levied on those countries that are not eligible for any preferential tariffs such as the US, China, or Australia. All these countries will now have improved access into the UK and will, therefore, put more competitive pressure both on UK domestic firms and on EU firms selling to the UK.

While tariffs have been removed (subject to the provisos given above), other costs of accessing the EU market come from an increase in non-tariff barriers and rules of origin. We now turn to these two issues.

Trade deals typically have a limited impact on border procedures: they do not remove border and customs formalities. This is true of the TCA, which does not include any simplifications for border formalities that could help minimise delays, congestion and bottlenecks. Indeed, it is important to recognise that leaving the EU creates extra barriers between the UK and the EU, which the TCA does not address. Estimates of the costs of completing customs declarations for the UK economy are estimated to be of the order of £15 billion.[3]

Like most modern trade deals, the TCA includes a chapter on Customs and Trade Facilitation. It is comprehensive and covers standard provisions as well as commitments under the World Trade Organization (WTO) Trade Facilitation Agreement (TFA), which in any case should be applied on an MFN basis. The chapter serves as a good basis for further cooperation and encourages parties to exchange customs-related data, promote transparency and enforcement as well as introduce potential further initiatives. However, these provisions are quite broad and the tangible impact on border procedures remains limited, especially since part of the chapter repeats the parties’ TFA commitments. The parties have also signed the Protocol on Mutual Administrative Assistance in Customs Matters and the Protocol on Administrative Cooperation and Combating Fraud in the Field of Value Added Tax and on Mutual Assistance for the recovery of Claims Relating to Taxes and Duties, which encourage cooperation in these areas.

One example of future initiatives mentioned in the TCA is a pilot for developing a mechanism to avoid duplication of customs information. This is similar to the UK’s earlier proposal for a three-year pilot[4]. Both parties seem keen to introduce such a pilot in 2021. Once completed it could lead to eliminating the duplication of customs procedures similar to what has been achieved between Norway (not in the EU) and Sweden (an EU member).

The chapter also includes special provisions for roll-on roll-off (ro-ro) ports. They are however limited to both sides allowing procedures for pre-lodgement and the use of various documents to process goods prior to arrival. The final version of the agreement includes looser commitments in this area than the proposal submitted by the UK earlier in 2020.

Finally, the agreement provides for mutual recognition of Authorised Economic Operator (AEO) programmes. This means that AEO holders from both parties will be granted similar benefits when it comes to customs clearance. These benefits are currently limited to taking the AEO status favourably into account when it comes to risk assessment, reducing the number of checks and controls or granting priority if inspections are required. In exchange for mutual recognition, the UK has committed to keeping its AEO programme compatible with that of the EU’s (the current version of the programme). While the agreement stresses that SMEs should be able to qualify, the current AEO criteria make it very difficult for SMEs and newly established companies to obtain such status.

In order to obtain tariff-free access to the EU market a UK firm has to show that the good was produced or ‘originated’ in the UK, and vice versa, and to do so it needs to meet the underlying ‘rules of origin’ (ROOs). The TCA includes bespoke rules of origin and full bilateral cumulation. The UK Government’s position is that these rules are ‘modern and appropriate’[5]. In evaluating the rules of origin typically there are three broad areas to consider: what are the underlying rules themselves; what are the provisions concerning cumulation and what are the administrative arrangements.

With regard to the first of these issues, there is no standard ‘international’ benchmark against which to assess the ROOs – because they tend to be specific to any given agreement. However, the first point to make here is that prior to January 1st 2020 the UK did not need to prove origin for goods exported to the EU. So, both in terms of the administrative requirement and in terms of the ability of firms to obtain preferential access, the current situation is worse. There have already been numerous reports in the press regarding firms not being able to meet origin requirements.[6] Another point of comparison could be the PEM rules – a common set of ROOs which the EU has agreed with 25 non-EU countries.

Rules of origin are normally based on one of four criteria:

These rules can also be used in combination such that for a given product, for example, there may be a choice of a VA rule or a CTC rule; or, for example, that both a VA rule and a CTC rule has to be met.

Two additional rules are used in the TCA much more than in previous EU agreements. The first is, rather than specifying a minimum percentage of domestic value added which a product must contain, is to specify the minimum weight of originating materials. This rule has been applied in the agri-food sector. Hence in the PEM rules of origin, the WO rule is used as the sole rule in agri-foods 65% of the time. In the TCA the WO rule is used solely 54% of the time, and for 12% of the goods the WO rule is combined with a minimum weight requirement. The CTC rule is also combined with a weight requirement in 7% of cases. The requirement to meet both rules, potentially makes it more difficult for firms to obtain originating status for their goods in comparison to the PEM.

The second rule which is used more widely in the TCA is an ‘any heading’ (AH) rule. This rule states that obtaining originating status requires ‘production from non-originating materials of any heading’. In the raw materials industries (see Table below) this rule is never used in the PEM, whereas it is used in 10% of cases in the TCA. This rule allows for the use of non-originating materials, even if the materials are from the same heading (eg. coal dust being used to produce coal briquettes), providing the working or processing involved exceeds the definitions of insufficient working or processing. This is a less restrictive rule, than one which requires a change in heading or a change in chapter.

Table 1 provides a comparison between the use of the different rules in the PEM system, and in the TCA.[7] Agri-foods are excluded from the table for expositional purposes, as the table becomes unwieldy, but the main differences between the TCA and the PEM have been outlined above. In the summary table we have grouped the use of the different rules by broad industry aggregate categories. The first four columns identify those cases where only one rule is used.

| CTC | VA | SP | AH | CTC or VA | CTC or SP | CTC & VA | CTC & VA, or VA | SP or VA & SP | More than 2 rules | |

| TCA Rules of Origin | ||||||||||

| Materials | 40% | 0% | 1% | 10% | 46% | 1% | 2% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Chemicals | 2% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 15% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 82% |

| Textiles | 11% | 0% | 72% | 2% | 4% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 9% | 0% |

| Adv. Manuf & Mach. | 0% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 95% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Automotive | 0% | 56% | 0% | 0% | 44% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Manuf. & Electronics | 1% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 93% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 1% |

| Pan-European Med Rules of Origin | ||||||||||

| Materials | 60% | 4% | 22% | 0% | 0% | 3% | 10% | 0% | 0% | 2% |

| Chemicals | 10% | 20% | 1% | 0% | 64% | 1% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Textiles | 12% | 1% | 65% | 2% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 18% | 0% |

| Adv. Manuf & Mach. | 0% | 43% | 0% | 0% | 8% | 0% | 0% | 49% | 0% | 0% |

| Automotive | 0% | 78% | 0% | 0% | 1% | 0% | 0% | 20% | 0% | 0% |

| Manuf. * Electronics | 10% | 47% | 1% | 0% | 4% | 0% | 1% | 37% | 0% | 1% |

| CTC = change in tariff classification; VA = value added rule; SP = specific production processes; AH = any heading; Other = where more than two rules in some combination are used. | ||||||||||

There are several messages from this table. First, the table reveals how complex and varied are the underlying rules of origin. Except for in textiles the use of one rule only applies to 50% or less of the products. Second, the distribution of the rules in the TCA is very different from those in the PEM, which will make any future diagonal cumulation very hard to achieve. Third, for some important sectors the rules in the TCA would appear to make it easier for UK firms to obtain originating status in comparison to the PEM. For example, in the automotive sector there is a much higher share of products for which the rule is either a VA rule or a CTC rule (44% in the TCA v 1% in the PEM), as opposed to just a VA rule (56% v 78%). The situation is similar in advanced manufacturing. Having a choice of rules applies in a higher proportion of cases in the TCA than under the PEM. Generally, having the possibility of more than one rule of origin is preferred by companies, and given that supply chains vary considerably even within the same industry, having a choice can be beneficial. In these sectors we also see that where the value added rule is used, the maximum value added share of non-originating materials appears to be higher.[8]

However, in other broad sectors it is less clear that the rules are more generous than the PEM. We have already discussed this with regard to the use of the weight and any heading rules in agrifoods and materials. But we also see that in Chemicals over 80% of cases the rules are a combination of more than three different rules in the TCA. Where this is the case, the rule is a combination of a change in tariff classification (at a more disaggregated level than in the PEM) and a specific production process, or a value added rule (which is more generous than in the PEM).

In summary, in comparison to the PEM, the rules of origin agreed between the UK and the EU in some cases appear to make it easier for firms to obtain originating status for their exports, but this is by no means always the case. Nevertheless, the TCA rules still involve higher barriers to trade and make bilateral trade more difficult in comparison to the UK being a member of the EU. One of the issues of concern in the automobile industry (where the value added rule is applied) was the high costs of the imported batteries incorporated in UK made electric vehicles. On this, the agreement allows for initially higher levels of third country content reducing over time to 35%, and this is likely to prove challenging for the industry.

However, the extent of this will also depend on the cumulation arrangements. The TCA allows for ‘full bilateral cumulation’, which means that both inputs as well as processing taking place in any one of the parties will count towards the origin of the final product. Hence, even if an EU intermediate product sent from the EU to the UK is not itself deemed as originating from the EU, UK firms can count the EU value-added in that product when using the input in a final good being exported back to the EU. With integrated supply chains this makes it easier to obtain tariff-free access, and once again will help to facilitate bilateral UK-EU trade.

However, no regional, diagonal or extended cumulation is agreed. Diagonal cumulation would allow inputs from third countries (ie non-EU or non-UK) to be counted as originating, but requires an FTA between all parties with identical rules of origin. The UK has agreed extended cumulation in many of its ‘continuity’ free trade agreements with third countries.[9] For example, in the UK-Japan free trade agreement, both parties agreed that EU inputs could count for originating purposes. The EU has agreed diagonal cumulation (which requires identical rules of origin) with the 25 non-EU PEM countries, as well as in some other agreements. However, since the UK-EU rules differ from the modernised PEM rules of origin, the EU would not agree to regional cumulation under the PEM system. It is worth noting that the Partnership Council may amend the rules of origin applicable under the TCA. The lack of diagonal cumulation will have an impact on those firms/sectors who rely more extensively on non-EU imported intermediate inputs and on suppliers of those goods. In the first instance, this is likely to mean that such goods will face tariffs on EU-UK trade, and in the long run it may result in a re-configuration of supply chains. This could result in more investment in bilateral UK-EU supply chains, or it could result in less investment in the UK as more production switches to the EU.

With regard to administrative processes, the agreement provides for two different types of origin certification, which do not require third-party certification:

In addition, the UK and the EU have agreed on 12 months of simplifications whereby the supporting documentation for claiming preferential origin will not be required at the time of import. While this was not part of the TCA agreement, it supports the implementation of the deal in its first year. Firms, however, may be required to subsequently provide the supporting documentation for any preferential exports/imports undertaken in this initial 12 month period. For these purposes the documentation may need to be kept for up to four years.[10]

A key issue in the debate over Brexit was the extent to which regulatory harmonization with the EU was necessary or desirable. For many in favour of Brexit, the argument was that free trade did not require regulatory harmonisation and that it was sufficient for every country to have mutually recognised conformity assessments systems. Singham et al (2018)[11] argued that the EU-UK FTA should acknowledge the right of testing authorities in both parties to confirm conformity with local production made to the other party’s mandatory standards, and went on to suggest that if the EU refused this the UK would have a strong case at the WTO that it was being discriminated against.[12]

This approach would mean countries could set their own national mandatory standards subject only to the global rules of the WTO and the TBT (technical barriers to trade) and SPS (sanitary and phyto-sanitary) agreements. But they would be obliged to accept goods made elsewhere that could claim to have been made to the importer’s standards with no need for further checks. Whether a country uses different domestic standards/regulations or not, it should be able to use its domestic regulatory system to certify that goods satisfied the importing country’s rules, so as to avoid the need for physical inspections at the border. This has long been a view expressed by the US. [13]

In its draft FTA, the UK proposed to the EU that full mutual recognition of certification should apply to industrial goods but with regard to food safety, it merely proposed technical cooperation on food regulations. Hence in its June 2020 proposal, the UK called for the continuing right of UK certification bodies who hitherto had the right to certify non-food factories and products – as complying with EU rules – to continue to do so. However, for some time the EU signalled that the UK’s demands were unacceptable, not only because such UK bodies would no longer be under the control of the EU and but also because UK certification bodies should not be given free access to the EU as suppliers of certification services.[14]

The TCA incorporates the EU view, not the UK’s. There is no chapter on mutual recognition of conformity assessment in general. This should be seen as a significant ‘loss’ for the UK and will serve to impede access to the EU market and increase firms’ costs of accessing the EU. The result of the TCA is that (with some limited sectoral exceptions) goods made in the UK for sale in the EU must not only conform to EU standards but they must provide EU-overseen paperwork to prove this conformity. For the least sensitive products, “self-certification” will be acceptable but the manufacturer will have to appoint an EU-based representative who will take legal liability if necessary. For goods which require third party certification the testing has to be carried out in the EU by an EU accredited body, which, for example, could be the Dutch branch of the British Standards Institute (BSI). It is worth noting that the BSI managed to negotiate continuing membership of European standards bodies CEN and CENELEC, for non-electrical and electrical goods respectively, but it is not clear if this will be permanent.

For products where the EU requires only self-certification the UK’s refusal to accept the CE certificates for use in the UK creates numerous complications. UK firms have to decide whether to stamp goods with UK CA labels (which will not be valid in Northern Ireland), UKNI labels (which are issued in Northern Ireland under the UK system for sale in NI or GB and must be accompanied by a CE mark), or the CE label (which can be used to certify compliance with EU regulations, where goods are made in UK to EU standards).[15] For exports in the EU from the UK, UK sellers have to create an EU subsidiary or nominate an EU based importer (agent) who accepts legal liability for conformity.

There are some sectoral exemptions, notably vehicles where UK Type Approval Certification is recognised so long as the UK sticks to the common UNECE set of rules.[16] This appears to be as good as the UK could hope for. There may still have to be inspections of paperwork.

On Chemicals, the UK has insisted on setting up its own rules regime and certification system to rival the EU’s REACH scheme.[17] The industry is deeply opposed to divergence and will have to incur the expense of duplication of registration and testing. Most third countries will insist on certification to EU standards which will have to be done by EU accredited bodies. There appears to be no mutual recognition of conformity assessment on chemicals, and the agreement calls for cooperation and information exchange.

The EU has agreed to accept UK certification of pharmaceutical plants as compliant with EU rules on “Good Manufacturing Practice” but not, for the time being, other aspects of the safety of products, which may therefore require safety tests on medicines to be carried out both in the UK and the EU. “Critically, the cooperation regime set up by Annex TBT-2 does not extend to batch release Privileged and confidential Attorney-client correspondence certification. From the EU’s perspective, this implies that each batch imported into the EU must undergo a full qualitative analysis, a quantitative analysis of at least all the active substances and all the other quality verifications”.[18]

For aerospace products, there are a complex set of rules which go some way towards mutual recognition of testing and certification allowing both sides to inspect the other’s facilities, with different regimes for design changes, minor and new, vs equipment safety. The aerospace text provides for negotiations between the EU and UK on a series of areas where mutual recognition may emerge. The UK side states “In addition, the Annex foresees the possibility of the EU extending their scope of automatic recognition of UK aeronautical products and designs once it gains confidence in the UK’s capability for overseeing design certification”. [19]

With regard to food products and animals, the TCA does not introduce any simplifications in terms of SPS checks and formalities. The TCA gives each party the right to insist that imports meet their standards. There is no mutual recognition of either product standards or testing. Great Britain will maintain an independent SPS regime while Northern Ireland will remain in the EU’s SPS area. For food products, there has to be testing potentially of all imports by the EU (including NI) from the UK. This contrasts with the EU’s treatment of New Zealand which requires that only 1% of imports need to be checked. However, the TCA encourages parties to keep the frequency of checks to a minimum, based on the level of risk. There are no provisions for a reduced level of checks or an equivalence mechanism for SPS measures under the TCA. Although strictly not part of the TCA, the UK was also granted National Listed Status by the EU meaning that live animals and products of animal origin can continue to be exported from the UK to the EU, though subject to stringent controls.

Economically, for the UK this is not a large industry as it accounts for close to 0.1% of GDP and employs around 25,000 workers in total (these figures include fish processing).[20] However, fishing has a symbolic significance which is tied up with the UK being a maritime nation. There is concern for the economic fate of fishing communities, and notably the issue of sovereignty over British waters.

The TCA provides for managing fisheries in accordance with the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982, establishes the objective that populations of harvested species should be above biomass levels that can produce the maximum sustainable yield (MSY), and identifies the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) as the main body responsible for providing scientific advice on management decisions.

The agreement provides regulatory autonomy of management decisions in each party’s waters, so the UK will not be bound to the EU’s Common Fisheries Policy (CFP) rules. Being able to deviate from the CFP and establish regulations that can be more responsive and specific to the situation in UK waters has always been an important issue for UK policymakers and for the industry.

The agreement provides for the continuation of reciprocal access to each other’s waters until 30 June 2026, as well as the continuation of the existing historical rights to fish in territorial waters between 6 and 12 nautical miles in the southern North Sea, English Channel, Bristol Channel and south-east of Ireland (ICES divisions 4c and 7d-g). This is a huge disappointment to inshore fishers in this area, who had hoped to regain exclusive access to the 6-12nm zone.

The level of access can be reduced in the future. However, the cost may be high: reciprocal access can be suspended, tariffs can be applied to fisheries products, and to other goods if it is considered necessary to compensate for the economic and societal impact suffered from loss of access to fish. Furthermore, it allows for obligations relating to trade and road transport (with the exception of the level playing field) to be suspended.[21],[22]

The agreement sets out a framework for the two parties to agree on the total allowable catches (TACs) for each stock. Setting the TAC – and subsequently dividing the TAC between the parties on the basis of agreed quota shares – is crucial for the sustainability of fisheries. A detailed process is also established for setting provisional TACs if there is no agreement for some stocks. This is an important step to sustainability and will help avoid the situation often seen for international stocks where a TAC may be agreed, but the total quota shares set by individual coastal states exceed the overall TAC.

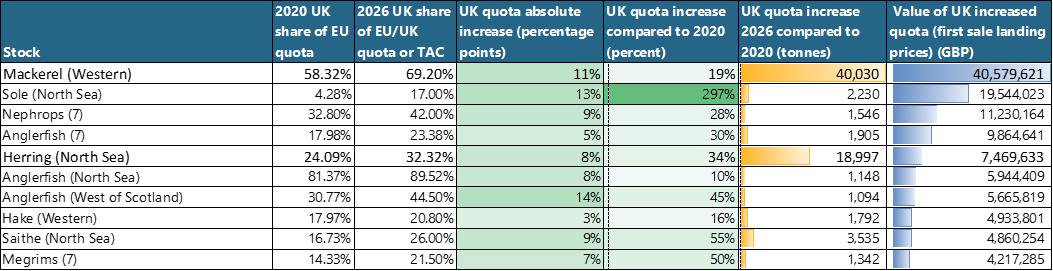

So much has been said in the UK about taking control of our waters and of the bounty of resources that we would have the rights to exploit as an independent coastal state outside of the CFP. However, the realities of the quota shares that have been set out in the agreement fall short of this. The UK will increase its share of the quotas over a five-year adjustment period, such that around 25% of the value that EU vessels previously caught in UK waters will be ‘repatriated’ to the UK. The increase in quotas is not uniform across stocks, with some stocks seeing no change, or even a reduction in quota. The ten stocks with the greatest potential increase in quota in terms of first sale value are shown in Table 2. The largest increases are for mackerel, North Sea sole, and Nephrops in the Irish Sea, Celtic Sea and English Channel (Area 7). Overall, in 2026, the additional quotas could be worth £149 million to the UK.[23]

Beyond these top ten stocks, the UK’s share of Celtic Sea haddock will double from the current 10% to 20% at the end of the adjustment period, and its share of hake in the North Sea, a species which has increased in abundance in recent years, increases from 18% to 53.5%. However, other increases are marginal – the UK’s share of sole in the Eastern Channel was 19.2% in 2020, and this increases to 20.0% in 2026 onwards. Furthermore, the iconic Eastern Channel cod, which was frequently highlighted by the industry as one of the injustices of the CFP quota shares (the UK receives just 9% and the French 84%), will have no change to quota shares. Although not a significant fishery (the overall TAC was just 858 tonnes in 2020), failure to demonstrate any change to the shares for this stock appears to be a political failure if nothing else.

There will be no tariffs applied to fish and fisheries products. This is a significant deviation from the arrangement that Norway has with the EU, in which fisheries products are excluded from tariff-free access under the European Economic Area (EEA) agreement. However, the fish quota sharing arrangements that Norway has with the EU are based on quantities of each stock that occur in each party’s zone (zonal attachment), something that the EU-UK agreement falls short of. Despite zero tariffs, there will still be non-tariff barriers that will increase friction for trade, such as the need for catch certificates and export health certificates.

Some other areas merit brief mention. A mechanism to allow for voluntary in-year quota transfers is anticipated, which will allow current EU Member States to continue quota transfers between the UK and EU, helping facilitate fishing businesses to match quota with catches. However, the mechanism by which these transfers will be effected has not yet been established, and there may be delays and difficulties in matching quota needs between industry and the responsible authorities. The role of the Specialised Committee on Fisheries will be important in determining the details of how the relationship between the two parties plays out, in areas such as data collection and sharing, enforcement, designation of landing ports and guidelines for access conditions. The agreement will be subject to a review every four years from 2030, to evaluate the arrangements such as access to waters, shares of TACs and quota transfers.

In summary, the changes are not very substantial, at least in the short term. The UK will have regulatory autonomy for fisheries. However, the pattern of fishing by EU and UK vessels will not change significantly, and access for EU vessels to the UK’s 6-12nm zone continues in southern England. The UK will receive higher quota shares for some stocks. There will be no tariffs on fish products, which will be important for businesses that export fresh and chilled fish and shellfish to the EU, as well as for EU consumers. However, there are additional trade (non-tariff) barriers, such as catch certificates and export health documents that will have to be completed, and customs processes to clear. The UK industry may find itself asking whether it was all worth it.

Trade agreements are normally concerned with liberalising trade. The TCA is highly unusual in that it is an agreement which raises barriers to trade. This will generate short- and long-run costs to the UK economy which have been well documented. Nevertheless, the costs of no-deal would have been greater still. In that context having some agreement should be viewed as a success in and of itself. To paraphrase Teresa May, ‘some deal is better than no deal’.

However, as discussed in our recent Briefing Paper on the ‘Costs of Brexit’, a deal with the EU only mitigates the costs of leaving the EU by around 20-25%.[24] This is because with regard to trade in goods, the deal is relatively shallow. There is complete elimination of tariff and quotas and this is unusual as most FTAs retain some tariff or quotas on some goods. However, the many other costs relating to trade have not been successfully minimized. There is no chapter on mutual recognition of conformity assessment, there is no diagonal cumulation of rules of origin, and in the fisheries element, the agreement is somewhat modest in comparison to the UK demands. This is disappointing. Taken together with the very low levels of ambition and agreement in services (see companion Briefing Paper, No.53); and the treatment of state aid, subsidies and the level playing field provisions (see companion Briefing Paper, No. 54) and in particular the possibility of rebalancing measures, the final agreement is much closer to the EU’s starting position than that of the UK.

While the agreement does allow for future renegotiation, which could in principle lead to improvement, at the present moment it is hard to have much confidence that this will be the way forward.

[1] Under the rebalancing provisions, if as a result of, for example, change in labour or environmental policies significant divergences emerge with material impacts on trade and investment, then either party can take appropriate ‘rebalancing’ measures – though these are not clearly defined. See our companion Briefing Paper no.54 for a more detailed discussion.

[2] See Gasiorek, Magntorn-Garret and Winters, https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/2020/05/20/new-tariff-on-the-block-what-is-in-the-uks-global-tariff/

[3] The UK-EU Trade Deal: what does it mean for UK Automotive? – Centre for Brexit Studies Blog (wordpress.com)

[4] Article 7.9, Draft Working Test for a Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement between the United Kingdom and the European Union, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886010/DRAFT_UK-EU_Comprehensive_Free_Trade_Agreement.pdf

[5] See: “UK-EU Trade and Cooperation Agreement”, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/948093/TCA_SUMMARY_PDF.pdf, para 19., p.8.

[6] See for example, Baffling Brexit rules threaten export chaos, Gove is warned | Brexit | The Guardian

[7] The summaries are based on identifying which rule applies for each product at the HS 6-digit level, which comprises more than 5000 products. For the purposes of the analysis the comparison is with the 2013 revision of the PEM system. See https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=OJ:L:2013:054:TOC

[8] If a product does not satisfy the VA or weight origin requirement, there are then tolerance thresholds. For Agrifoods (Chapter 2 and 4 to 24 of the HS system) a product is considered as originating if the total weight of the non-originating does not exceed 15% of the weight of the final product (except processed fishery products of Chapter 16). For all other products, the total value of non-originating materials does not exceed 10% of the ex-works price of the product (this rule excludes products classified under Chapter 50 to 63 of the HS as there are specific tolerance thresholds detailed in Notes 7 and 8 of Annex ORIG-1

[9] As a member of the EU, the UK was also party to the many free trade agreements the EU had signed with third countries. The continuity agreements are agreements between the UK and these third countries which largely replicate the previous arrangements the UK had as an EU member.

[10] There is some lack of clarity between the EU and the UK official documents as to whether documentation will need to be kept for three or four years, and the rules vary slightly depending on who is doing the self-certification.

[11] Shanker A Singham, Radomir Tylecote and Victoria Hewson IEA Discussion Paper No.91 Freedom to

Flourish: UK regulatory autonomy, recognition, and a productive economy, July 2018 IEA, pp 32-37

[12] This approach was reflected in the UK’s draft FTA unceremoniously reflected by the EU, see https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/publications/uk-eu-free-trade-agreement-please-sir-i-want-some-more/

[13] Source interviewed in Washington 2017

[14] ibid

[15] See https://www.gov.uk/guidance/using-the-ukni-marking

[17] See https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/publications/uk-eu-free-trade-agreement-please-sir-i-want-some-more/

[18]Van Bael and Bellis ; “Medicinal Products under the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement” :https://www.vbb.com/media/Insights_Articles/TCA_Medicinal_Products_04012021_003_.pdf

[19] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/948093/TCA_SUMMARY_PDF.pdf , para 104

[20] Source: The UK Fishing Industry (2017), House of Commons Library, Debate Pack no. CDP 2017/0256

[23] ABPmer, 2021. EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement – Thoughts on Fisheries from a UK Perspective. ABPmer White Paper. January 2021. Available at https://www.abpmer.co.uk/blog/white-paper-eu-uk-trade-and-cooperation-agreement-thoughts-on-fisheries-from-a-uk-perspective/.

[24] See: UKTPO Briefing Paper 51, The Costs of Brexit: https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/publications/the-cost-of-brexit/ – the authors find that the net effect of the TCA is that the UK’s GDP will be 4.4% lower than in the absence of Brexit, compared with 5.5% lower if there had been no deal.