Does CPTPP threaten UK food standards?

Access to the regulatory/risk assessment process

Differences between the CPTPP SPS Chapter and existing UK FTAs

Does CPTPP accession prevent the UK from agreeing to continued regulatory alignment with the EU?

While it might at first glance appear somewhat technical, the influence of trade agreements in shaping UK food safety and standards has become almost existential in defining the UK’s post-EU identity. Indicating the extent of concern from MPs and interest groups, the UK Government established a specialised Trade and Agriculture Commission in July 2020 to ensure that animal welfare and environmental standards in food production are not undermined and scrutinise the impact of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) on UK food standards.[1]

There has also been controversy about how to manage the consequences of EU regulatory divergence between Great Britain and Northern Ireland arising from the Northern Ireland Protocol. One option is to align temporarily with EU agri-food regulation through a veterinary agreement. In refusing this option, Lord Frost stated that: “The reason isn’t ideological, it’s because to do trade agreements with other countries you need to have control of your own agri-food and SPS [Sanitary and Phytosanitary] rules”.[2] He has argued that joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) would prevent this alignment between the UK and the EU.[3]

In this politically charged context, acceding to the CPTPP is far from ideology-free. It symbolises the UK’s desire for regulatory independence from the EU and sets out a new post-Brexit direction. But this is also the starting point for more questions, for which an understanding of the technical ins-and-outs of the relevant Free Trade Agreement (FTA) provisions, as well as the particular export interests of CPTPP countries, is crucial. In this Briefing Paper, we look at two of these questions: first, does CPTPP accession seem likely to lower UK food standards? Second, does CPTPP accession prevent the UK from agreeing to continued regulatory alignment with the EU?

The CPTPP provides for broad and deep tariff elimination: up to 99.9% of tariff lines for UK exports will be duty-free once fully implemented.[4] CPTPP parties (Table 1) have maintained tariff-rate quotas (TRQs), an incomplete form of tariff liberalisation, in sensitive agricultural areas, and set out thresholds at which they will introduce very high agricultural tariffs that respond to market shocks, known as safeguard measures.[5] Theoretically, the UK Government can replicate this when, as part of its accession process, it agrees its tariff concessions with CPTPP parties. However, the UK’s strategy in the Australia-UK FTA Agreement in Principle (AIP) indicates the possibility that the UK may agree to liberalise completely. The UK-Australia AIP commits to staged tariff phase-out for all agricultural products barring long grain rice. This marks a shift from the UK’s previous approach to agricultural trade in its EU-derived FTAs (the continuity agreements), which maintain some TRQs.

| CPTPP Party | Agricultural products covered by TRQ |

| Canada | Dairy (Milk, cream, butter, cheese, etc)

Chicken Turkey Eggs |

| Japan | Wheat flour

Udon Barley Dairy (Milk, cheese) Coffee, tea mixes and dough Peas, beans and legumes Candies Chocolate/cocoa Sugar/sucrose + Country-specific TRQs for products including rice |

| Malaysia | Poultry

Swine Milk Eggs |

| Mexico | Milk

Butter Cheese Palm Oil + Country-specific TRQs for sugar |

| Viet Nam | Tobacco |

The table shows that not all CPTPP parties have TRQs and that those that have them have focused mainly on the areas of dairy and meat. The UK currently has relatively high tariffs across these areas, in the region of 30-60%.[6] Thus, if the UK removed all tariffs and quotas it would be doing so on a non-reciprocal basis, in other words, offering tariff-free access to UK markets whilst trade partners maintain TRQs on UK products. It is thus crucial to understand what reciprocal tariff concessions have been undertaken as part of the UK’s bilateral FTAs with CPTPP Partners through both EU continuity agreements and negotiations with Japan, Australia and (forthcoming) New Zealand. This will aid in assessing the potential impact of full duty-free quota-free trade: which UK sectors are likely to be most exposed to increased imports, given existing trade flows and the relatively high tariffs the UK has imposed. The UK’s CPTPP tariff strategy is unknown and the recent Strategic Approach to the CPTPP document does not address this issue in detail.[7]

Increased competitive pressure on the UK farm sector from tariff removal is also linked to concerns about a reduction in UK animal welfare and environmental standards. Tariff removal adds to this concern because, for a number of animal welfare standards, producers outside the UK are not required to meet UK standards in order to access UK markets. These include the prohibition of battery cages, sow stalls, hot branding, and the use of preventative antibiotics.[8] When UK producers are required to adhere to higher standards, it drives up production costs. Tariffs help level the playing field for UK producers in these areas.

Table 2[9] reports some summary statistics for each of the product categories covered by the CPTPP countries’ TRQs.[10] The first column of the table gives the share of the TRQ covered products in that country’s total exports; the second column gives the number of HS 6-digit codes included in these categories; the third column indicates how many of those 6-digit codes are not exported by the country; the fourth column gives the share of the product codes for which the country has a negative revealed comparative advantage indicating a lack of competitiveness in world markets[11]. The final two columns provide information for the UK. The first of these gives the share of the covered products in UK exports, and the second gives the number of these products for which the UK has a positive revealed comparative advantage which suggests it is competitive in world markets.

| Export Share | Number | No exports | Neg RCA | UK Exp share | Pos UK RCA | |

| Canada | 1.02% | 56 | 0 | 82% | 1.49% | 20 |

| Japan | 0.21% | 50 | 5 | 100% | 1.27% | 22 |

| Malaysia | 0.13% | 16 | 2 | 82% | 0.22% | 4 |

| Mexico | 0.03% | 19 | 8 | 100% | 0.47% | 6 |

| Vietnam | 0.01% | 3 | 1 | 100% | 0.00% | 0 |

Several messages emerge from this table:

(a) and (b) together make it clear that the objective is to protect domestic producers and markets from imports, and not because of any strategic offensive export interest. They establish the principle within the CPTPP of protecting certain products / sectors, unlike the UK’s approach in its negotiations with Australia. Hence, while the UK is not likely to be exposed to increased imports in these sectors from these countries, it may be exposed in other sectors which may be of importance from a political economy perspective in the UK, and may be important from the perspective of the maintenance of food standards. In sum, (1) some CPTPP parties have not been shy about using TRQs to protect sensitive agricultural industries, an approach which the UK could clearly emulate; and (2) to understand more fully the export interests of CPTPP parties, it is also important to ascertain export interests and UK shares for CPTPP parties without TRQs, and for agricultural products that aren’t covered by TRQs.

Sanitary and Phytosanitary (SPS) regulations cover the areas of human, animal and plant life and health. SPS chapters of FTAs address border controls and regulatory risk assessment to ensure that agri-food products moving between Parties are safe with respect to these goals. They also address how countries can reduce regulatory barriers and the need for border checks. The Obama Administration’s objective in joining the CPTPP (then TPP) was to export US influence to the Pacific region.[12] Thus, even though the Trump Administration pulled out of the agreement, CPTPP obligations reflect what Wagner described as a ‘blueprint for future SPS governance’ which the US wished to export globally.[13]

The UK, like the EU, is somewhat of an international outlier in its ‘precautionary’ approach to risk assessment. The precautionary principle allows regulatory action even in the absence of conclusive scientific evidence. It takes into account that evidence of harms may not yet have emerged, or that scientific evidence may conflict.[14] The US has rejected the use of the precautionary principle and relied more upon international standards and a ‘science-based’ approach.[15]

In practice, this means that the UK is on the verge of agreeing to an FTA forged from the same negotiating objectives that caused controversy with respect to the US and its ‘chlorinated chicken’. It should be noted that the US Trade Representative recently described the CPTPP as ‘outdated’,[16] and the Biden Administration has promised a new US FTA strategy when (and if) the US pursues an FTA with the UK. However, US negotiating objectives in this area derive from Congressional objectives enshrined in legislation, and likely still by and large hold.[17]

Comparing Trump Administration UK negotiating objectives and CPTPP SPS obligations reveals strong similarities:

Establish rules that further encourage the adoption of international standards and strengthen implementation of the obligation to base SPS measures on science if the measure is more restrictive than the applicable international standard.

Similarly, the CPTPP requires that:

Each Party shall ensure that its sanitary and phytosanitary measures either conform to the relevant international standards, guidelines or recommendations or, if its sanitary and phytosanitary measures do not conform to international standards, guidelines or recommendations, that they are based on documented and objective scientific evidence that is rationally related to the measures…. (CPTPP Article 7.9(2))

This language reduces the scope for CPTPP Parties to rely upon a WTO exemption that allows regulation when scientific evidence is uncertain subject to certain conditions – a limited application of the precautionary principle (SPS Agreement Article 5.7).[18] The rejection of precaution forms the basis for the US argument that a number of existing UK product bans or restrictions, including on the use of hormones in cattle, pathogen reduction treatments, GMO foods and pesticides, should be overturned. They also encourage use of international standards. International standards, established in Codex Alimentarius, allow for use of, or higher tolerances of, some of these substances than permitted in the UK, including pesticide residues and hormones/beta antagonists. [19] Unlike the animal welfare standards described above, these are regulatory areas where imported products are subject to bans where they do not conform with UK requirements, thus constituting a trade barrier that CPTPP Parties may wish to overturn.

The obligation in the CPTPP is exempted from binding dispute settlement, which means that countries could not challenge the UK to a CPTPP dispute on the basis that it wasn’t adhering to international standards or objective scientific evidence. However, the language provides the basis for a diplomatic challenge. In other words, if the UK has signed up to basing its regulations on ‘objective scientific evidence’ alone, CPTPP parties can strongly challenge the UK’s decision not to abide by this requirement. The question is how much pressure the UK will experience, and at what point in the process – during accession or afterwards. It is unclear whether this is a high priority for existing CPTPP Members. The agreement is fairly new, and it doesn’t have a Secretariat that provides a centralised repository of documents and meeting minutes. Because the UK can’t change central CPTPP obligations, it must use negotiations as an opportunity to determine the extent to which CPTPP parties see UK SPS regulations as a trade barrier. If it does not, this will likely suggest that maintaining its precautionary approach to food regulation is not a high priority for the UK.

Another key requirement has to do with access to the regulatory process. The US negotiating objectives for the UK state:

Include strong provisions on transparency and public consultation that require the UK to publish drafts of regulations, allow stakeholders in other countries to provide comments on those drafts, and require authorities to address significant issues raised by stakeholders and explain how the final measure achieves the stated objectives.

In CPTPP:

Each Party shall…conduct its risk analysis in a manner that is documented and that provides interested persons and other Parties an opportunity to comment, in a manner to be determined by that Party (Article 7.9(4)b)

The ability for interested persons to comment on risk assessment contributes to regulatory transparency and accountability. However, it also introduces a direct channel of communication between foreign corporate lobbyists, as ‘interested persons’, and UK regulators.

The CPTPP SPS chapter also provides additional avenues for Parties to request the removal of regulation that obstructs exports. A Committee oversees the implementation of the chapter, and there are regular meetings where Parties can raise concerns about other parties’ regulation. Parties are encouraged to acknowledge that their regulations are equivalent, and required, upon request, to explain the objective and rationale of their regulations (Article 7.8(2). None of these requirements bind the UK to a particular course of action. However, cumulatively, they will likely expose UK regulators and officials to new pressures. This again points to the importance of using CPTPP accession negotiations to identify the strategic interests of CPTPP Members in relation to UK SPS regulations.

The first stage of CPTPP accession involves determining whether any UK regulation must be changed to accommodate the Agreement. This is an opportunity for the UK to make clear that it does not consider that the above provisions constitute grounds to change the UK’s regulatory approach. This is in keeping with its CPTPP Strategy, which states that ‘the government remains firmly committed to upholding our high food safety and animal welfare standards….the UK will ensure that accession negotiations with CPTPP are consistent with our domestic interests and the government’s policies and priorities’.[20] If any CPTPP Parties object to this interpretation of the SPS obligations, the CPTPP allows Parties to opt-out of certain elements of the Agreement through the use of so-called ‘side-letters’. If other CPTPP Parties consider that the UK doesn’t currently conform with the CPTPP approach to SPS regulation, one way for the UK to maintain its existing approach to SPS regulation and risk assessment, for this and future FTA negotiations, would be to use side letters to opt-out of elements that reduce its ability to regulate on a precautionary basis, such as Article 7.9(4).

The CPTPP marks a move away from the approach to food standards that the UK has maintained in the FTAs that it has ‘rolled over’ from the EU. [21] The EU FTAs that the UK has adopted encourage international SPS standards, but also allow countries to set higher standards (see WTO SPS Agreement, Article 3.1). In the SPS chapters in its FTAs, the EU references the WTO as setting out the basis of its risk assessment approach.

This question may be academic, given that the UK Government has expressed no interest in continuing to align its regulation with the EU’s. Nonetheless, the claim that there is a direct clash between FTAs, such as CPTPP, and EU veterinary agreements is significant in revealing that FTA SPS chapters play a role in UK domestic politics and regulation. In this spirit, the logic behind Frost’s assertion that a veterinary agreement with the EU would conflict with UK FTA strategy should also be examined. Currently, UK agri-food regulations largely de facto conform with the EU’s. The UK maintains the right to change, but significant substantive revision has not occurred.[22] If complete alignment with EU regulations through a Swiss-style agreement clashes with CPTPP SPS obligations, this suggests that current UK regulations also clash with these objectives. This again raises the question: irrespective of a Swiss-style agreement, are current UK (aka EU regulations) consistent with CPTPP-style obligations? Frost’s own logic suggests that this is questionable. If that is the case, then the logic of the position taken by Frost is that in joining the CPTPP the UK would have to change its regulatory approach.

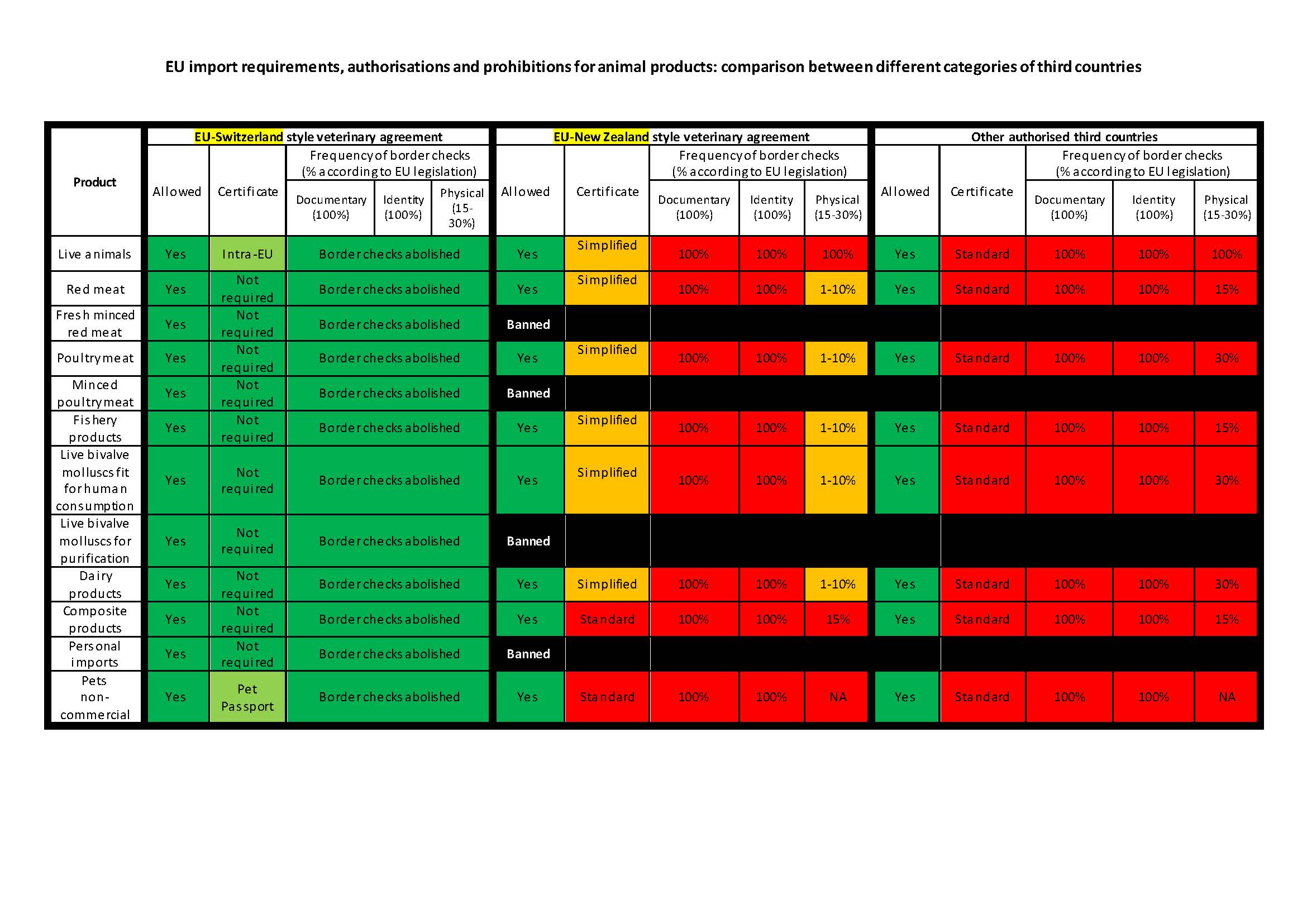

It’s not entirely accurate that an EU veterinary agreement is incompatible with the CPTPP. New Zealand, for example, has a veterinary agreement with the EU and is a Party to the CPTPP. However, as the graphic below, prepared by the European Commission, demonstrates, this style of agreement would do little to offset the increased occurrence of border checks. Whether complete alignment with EU regulation through a ‘Swiss style’ veterinary agreement clashes with CPTPP SPS obligations, like many areas of trade law, is open to interpretation. Rather than prescribing particular regulatory changes, for instance, the automatic lowering of pesticides Maximum Residue Levels upon ratifying the CPTPP, the CPTPP obligations summarised above are process-oriented and open-ended. In this example, those whose interpretations are most relevant are CPTPP Parties. This underscores the importance of the UK’s accession process in establishing the particular interests of other CPTPP Parties in overcoming UK agri-food trade barriers, including whether they might be likely to use CPTPP mechanisms in order to raise objections over the UK raising its standards higher in the future.

Certainly, having different standards and approaches in different agreements is possible: providing conformity can be established, the UK could argue that it would maintain alignment with EU regulation domestically, but develop separate export lines for the CPTPP. This would require CPTPP exporters to meet standards that were de jure, and not just de facto, those of the EU.

It is possible to interpret the UK’s positioning of FTAs as incompatible with a veterinary agreement as simply a convenient external lever to solidify its regulatory independence from the EU. Viewed differently, the UK Government’s political premium on (de jure if not de facto) abandoning the EU approach to food standards through FTAs appears to justify ongoing concerns about the weakening of UK food standards. As set out above, the difference in approach to agri-food regulation in the CPTPP and EU-model FTAs relates to the EU’s increased use of the precautionary principle to justify going beyond relevant international standards for agri-food regulation.

Source: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/20210518_coloured_table_agreements_with_third_countries_in_sps_area.pdf?utm_source=EU+Matters&utm_campaign=2f86de407e-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_BREXIT_BRIEF_21-10-20_COPY_01&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_e23b97fbd4-2f86de407e-543369982&mc_cid=2f86de407e&mc_eid=49c33ad4ff

In sum, the UK Government should be wary of adopting an uncritical approach to CPTPP accession. Failing to adequately understand or anticipate the interests of Parties could prove detrimental to upholding the UK’s strategic objectives, including maintaining current levels of protection in food standards and safety. It could do so directly through increasing pressure on UK regulators and also indirectly through increasing competitive pressure on UK farmers. This points to the need to use accession negotiations to address concerns in the agri-food area. These include clarifying the particular interest of CPTPP Members in addressing the UK’s existing SPS trade barriers, and the extent to which they are likely to object to the UK raising its standards in the future.

Even if CPTPP parties have little interest in exporting agricultural products to the UK, or pressuring the UK to change its standards is not a strategic priority, it would still be useful for the UK to communicate clearly in the first phase of accession that it does not intend to lower its existing standards. This is because future trade partners may demand similar commitments in their UK SPS chapters. To some major agricultural exporters who are also prospective FTA partners, such as the US and Brazil, acceding to CPTPP may mark the UK willingness to move away from the EU approach to risk assessment. If the UK’s own interests are not to lower standards, a clear written statement of the maintenance of the precautionary approach to risk assessment through this negotiation, preferably through side letters, would help address concerns about not only current, but also future, lowering of standards.

[1] https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/trade-and-agriculture-commission-tac

[2] The UK’s new relationship with the EU, European Scrutiny Committee Evidence session, 17 May 2021. Available at: https://parliamentlive.tv/Event/Index/0da61fda-7a2a-48e4-ad74-64ff1542d39f

[3] As reported by Lisa O’Carroll, Guardian Brexit correspondent, 24 June 2021: https://twitter.com/lisaocarroll/status/1408118552750608389

[4] According to the UK Government’s projections: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/995485/cptpp-strategic-case-accessible-v1.1.pdf

[5] https://www.international.gc.ca/trade-commerce/trade-agreements-accords-commerciaux/agr-acc/tpp-ptp/text-texte/toc-tdm.aspx?lang=eng&_ga=2.216861599.882715638.1626192241-806071118.1626192241

[6] https://www.trade-tariff.service.gov.uk/sections

[7] https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/995485/cptpp-strategic-case-accessible-v1.1.pdf

[8] Concerns about these areas have been raised regarding the UK-Australia Agreement in Principle; see eg this statement from Shadow International Trade Secretary Emily Thornberry: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2021-06-17/debates/DF2CB17B-E9E3-4EEE-927F-830828622A9A/FreeTradeAgreementNegotiationsAustralia

[9] Prepared by Guillermo Larbalastier, UKTPO Fellow.

[10] For each product category we have taken all the HS 6-digit codes covered by that category even though it is possible that not all codes are covered by the TRQs.

[11] Own calculations based on the normalised Balassa index of revealed comparative advantage.

[12] https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-china-38060980

[13] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312447622_The_Future_of_SPS_Governance_SPS-Plus_or_SPS-Minus

[14] Jacqueline Peel, ‘Risk Regulation Under the WTO SPS Agreement: Science as an International Normative Yardstick?’ (2004), http://jeanmonnetprogram.org/archive/papers/04/040201.pdf

[15] https://www.dfat.gov.au/sites/default/files/7-sanitary-and-phytosanitary-measures.pdf

[16] Under the Biden Administration the US, has signalled that it will revamp its approach to environmental issues in trade agreements and characterised CPTPP as outdated: https://thehill.com/opinion/international/544044-will-new-nafta-block-bidens-progressive-regulatory-policies

[17] Executive Office of the President of the United States (2020), National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers (page 139), https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2020_National_Trade_Estimate_Report.pdf ; Government of the United States (June 2015), Public Law 114-26, https://www.congress.gov/114/plaws/publ26/PLAW-114publ26.pdf

[18] Jacqueline Peel, ‘Risk Regulation Under the WTO SPS Agreement: Science as an International Normative Yardstick?’ (2004), http://jeanmonnetprogram.org/archive/papers/04/040201.pdf

[19] National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers, 2020, US Trade Representative, pp. 185- 193: https://ustr.gov/sites/default/files/2020_National_Trade_Estimate_Report.pdf

[20] Pp. 20-21. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/995485/cptpp-strategic-case-accessible-v1.1.pdf.

[21] For an example, the UK-Canada Trade Continuity Agreement, 22 December 2020, Annexes 5-A to 5-I reveal how minor the changes made have been. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/942941/CS_Canada_1.2020_Agreement_on_Trade_Continuity_UK_Canada.pdf

[22] In a previous Briefing Paper we examine in depth procedural changes that have occurred as a result of EU-exit legislative processes: https://blogs.sussex.ac.uk/uktpo/files/2019/10/UKTPO-Briefing-Paper-37.pdf