Dr Sam Power, Lecturer in Corruption Analysis at the Centre for the Study of Corruption, University of Sussex has co-authored a new report on election financing during the UK 2019 General Election. The International IDEA report was co-authored with Dr Kate Dommett, University of Sheffield; Dr Amber Macintyre, Royal Holloway; and Dr Andrew Barclay, University of Sheffield. The report finds that many types of campaign activity, especially digital campaigning, is not reflected in spending categories and that different political parties are not consistently coding the same activity under the same category.

This article was originally published on the International IDEA Blog on 15 June 2022.

While the the United Kingdom is often considered to have one of the most transparent political finance systems, it is still unclear how more than 1 in every GBP 10 was spent at the last UK general election. This is one of many findings from the International IDEA’s latest report, ‘Regulating the Business of Election Campaigns: Financial Transparency in the Influence Ecosystem in the United Kingdom‘, which investigates the companies, suppliers and individuals that political parties spend money on.

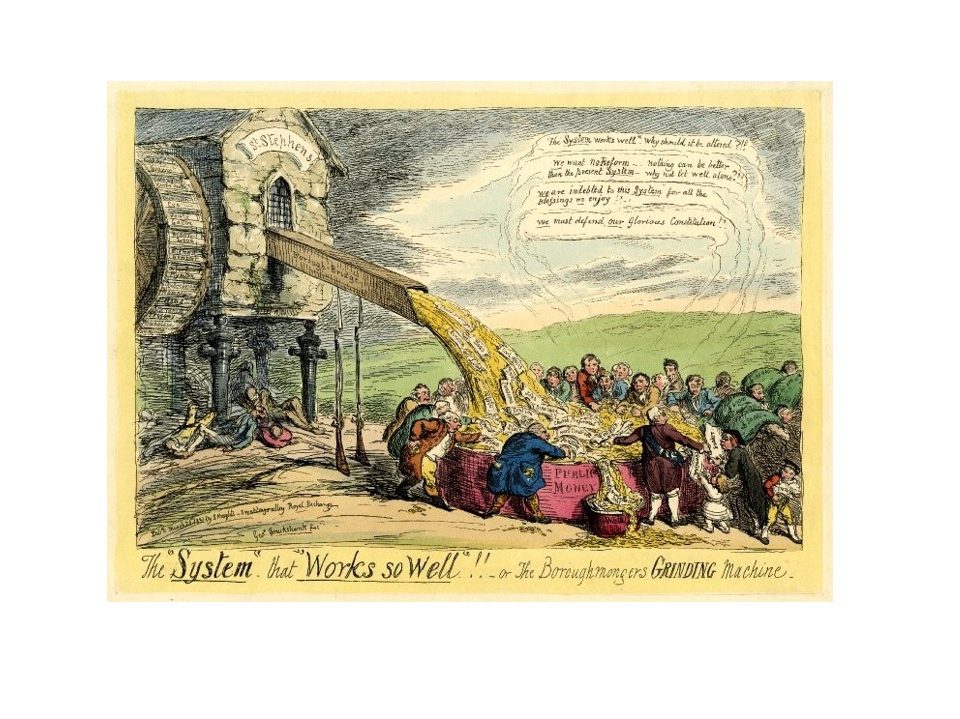

Getting to grips with the flow of money in politics is essential for understanding how the wider influence ecosystem at elections operates. Suppliers consult on election messaging and polling, provide social media tools and devise large-scale advertising campaigns. And as the Cambridge Analytica Scandal showed—such services during election campaigns matter and can be the cause of great public concern.

Mapping the influence ecosystem at elections – new trends and old realities

The new report looks at the UK as a case study to begin mapping this terrain. The country has one of the most transparent political finance regimes in the world. One of the particularly novel regulations is that if a political party spends over GBP 200 on anything at an election, they are required to provide an invoice from the supplier. These invoices are then released, with other details of election spending, on the Electoral Commission’s political finance database. By going through every invoice, and manually coding the service provided into new categories, the report confirmed much that was either assumed or found things that simply were not known about election campaigning in 2019.

For example, much has been written about digital advertising and, indeed, the democratic implications of the increased use of the online space. But the UK Electoral Commission’s political finance database is yet to capture how prevalent these trends are. There is no category for ‘online’, or ‘social media’ advertising. There is simply a catch-all ‘advertising’ designation. This means that researchers attempting to gauge the extent to which advertising occurs online had to previously rely on (very educated) guesswork, often based on keyword searches for prominent examples of companies (like Facebook and Google). This neglects that other suppliers (like consultants or advertising agencies) may—as a part of the service they provide—place online ads. The report found that of the over GBP 10 million that was spent on advertising, 73 per cent was done online. And over 50 per cent of this was on social media ads specifically. This suggests, for anyone thinking about how to regulate modern political advertising, online is key.

And yet, old realities still matter. Lost amongst some of the more alarmist perceptions of this new political world is that campaigning is still very much a ground game. The Internet is not the only fruit. In fact, by far the most prominent form of spending by parties—coming in at over GBP 21 million—was through campaign materials. This includes printing posters, leaflets and leaflet delivery which make up just over 40 per cent of all spend. That is not to say that online trends aren’t concerning. A little money can go a long way at elections as it is much cheaper to advertise online. Likewise, the GBP 50,000 spent on a campaign consultant might form the message which is then put out in a GBP 2 million leaflet drop (and targeted to certain demographics on Facebook). But the fact remains, most election spend is on incredibly functional—and much less immediately newsworthy—services.

What is unclear?

Despite all this, there is much that the report cannot fully capture. During the project, the research team placed all invoices that they couldn’t categorise into a separate ‘unclear’ heading. This might happen for several reasons. It might be that a blank invoice was submitted, or no invoice was provided at all. Some were blurry, and one even had a post-it note over the description of the service. Finally, there were some that would be so vague as to be useless—like the invoice that was for ‘persuasive and shareable content for the general elections’. Whilst some of these are, of course, more unclear than others, this remains a problem. It is impossible to tell exactly what 14 per cent of total election expenditure in 2019 was spent—that is a GBP 6.6 million black hole.

What can be done?

This matters. It is currently possible to provide very little meaningful information about services, or to deliberately abstract the information that political parties disclose. Therefore, it is impossible to make a reasonable judgement about what is, or is not, a problematic democratic practice. The report suggests a number of actionable legislative reforms that should be introduced to address these transparency deficits. The categories that are used in the Electoral Commission’s database should be updated to better reflect the realities of modern campaigns, particularly as it relates to digital advertising. More should also be done to standardise invoicing practice to reduce the possibility of genuine error or deliberate obfuscation. These are small reforms that will have a big effect. They will embed the UK’s reputation as a model of best practice. More importantly, they will allow the public to better understand how elections are changing—and map the actors that operate within the wider influence ecosystem—to more carefully diagnose any larger, perhaps more existential, democratic concerns.

Political finance transparency plays a key role in safeguarding the integrity of political processes and institutions. International IDEA is committed to supporting countries in developing digital solutions for political finance reporting and disclosure and to conduct in-depth country case studies in advancing the evidence-based global policy debate for better political finance transparency.

International IDEA’s report “Regulating the Business of Election Campaigns: Financial Transparency in the Influence Ecosystem in the United Kingdom” was drafted by a team of UK experts, led by Dr Kate Dommett (University of Sheffield) and Dr Sam Power (Centre for the Study of Corruption, University of Sussex), in collaboration with the Institute’s Money in Politics Programme. The report is available at the following link.

Recent Comments