22 May 2024

David Henig is Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). He has written extensively on the development of UK Trade Policy post Brexit, in the context of developments in EU and global trade policy on which he also researches and writes. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and former Director of the UKTPO.

One of the most heralded claims for Brexit was taking back control of UK international trade policy. Four years later, this is not widely seen as having been a success. Trade growth has been disappointing, the UK has become less open, exporting is still heavily concentrated in the Southeast of England, and there is little trust in Government pronouncements on trade. And yet there is almost no coherent discussion of trade policy and no evident strategy guiding future policy objectives or the signature of new trade agreements.

Part of the issue is that thinking about trade policy is trapped in the remnants of the Brexit debate and substantially seen in party political terms; it is consequently lacking any broadly accepted understanding. This is unsatisfactory and as part of the solution we propose to return the UK Board of Trade to its former status as a centre of excellence offering advice to the government and a source of impartial public information on international trade policy. Our paper is not the first to suggest that the Board of Trade be revived from its current somnolence, but it is the first to propose some details and a road map for that revival.

Our restructured Board of Trade would be a non-departmental public body – a well-established form for similar functions offering public service where there is a significant advantage of operational independence. It would be largely independent of government but nonetheless, work alongside government and all stakeholders to significantly elevate the UK’s trade policy debate and trade performance.

What would a restructured Board of Trade do?

The Board’s most prominent task would be to produce an annual report on UK trade performance and assess major new trade-related policies including trade agreements. This would be produced after extensive consultation with stakeholders and would be made public in an accessible form and debated in Parliament.

The Board would provide two impact evaluations of major prospective free trade agreements (FTAs), one at the stage of conception to see if it was worth pursuing and what the negotiating mandate should be (as the government currently does), and one close to completion of the negotiations, which would provide public information and sufficiently detailed analysis to allow Parliament to have an informed debate about whether to ratify the agreement. (Improved Parliamentary scrutiny of FTAs would be a second element of our improvement plan.) The Board would also conduct ex post evaluations of previous agreements in order to optimise them and learn lessons for the future.

Many modern trade problems concern regulation and trade, particularly in services. For example, there is a growing body of trade and climate change regulation, where there will be impacts both on trade and wider policy objectives. The Board would be required to consider major interfaces between trade and regulation, explaining them to the public and policymakers and helping with solutions.

Finally, we envisage a series of reports on specific trade and trade policy developments. These may include both detailed exercises to underpin future policy and simple explainers for the interested public.

Underpinning the Board’s work, there should be substantial and substantive engagement with Parliamentarians, stakeholders and the public. This would be partly aimed at improving policy and policymaking by encouraging a broad range of inputs, but also at building confidence that the UK had a satisfactory and inclusive approach to trade.

A model for a restructured Board of Trade

The challenge in designing a new Board of Trade is to create a balance between expertise/experience, independence from government, stability in the long-term policy vision and the fact that government, and to a lesser extent Parliament, must have a material role in the composition of a body with which they are intended to work closely. We suggest one model but recognise that others are possible.

Maintaining good relations between the Board and the government will be necessary for the former’s success. Hence, in our model, the relevant Secretary of State would continue to be termed the President of the Board of Trade and should appoint the members of a small politically balanced Board. These would have input to the Annual Report and formally receive it.

The main leadership of the Board’s work, however, would come from a Trade Council, with broad representation and expertise/experience in trade (not just exporting!). The Secretary of State would appoint the Council Chair in consultation with the relevant Parliamentary Committees and also a few members of a Trade Council. The majority of the Council would be nominated by the Chair and the whole Council approved by the small formal Board. The Chair would also appoint a Chief Executive Officer to lead the day-to-day work having consulted the Chairs of the relevant Parliamentary Committees.

The reconfigured Board of Trade should be established in legislation and have a guaranteed role in informing Parliament. It could, however, be created in shadow form virtually as soon as a government desired it, with formal statutory establishment following later.

By looking at similar UK institutions and the Swedish National Board of Trade, we estimate that the Board might require a staff of around 90 and an annual budget of about £10 million. At least some of these would come from the transfer of existing functions and staff from inside government. Lest this seems like a lot in our current straitened circumstances, recall that around one-third of UK consumption and investment comes from imports and around one-third of output is exported.

Getting trade right is important! Our proposal fills what is an obvious gap in current arrangements, with a view to building the broad consensus that is essential to a successful trade policy.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher May 22nd, 2024

Posted In: UK- EU

23 April 2024

23 April 2024

Adriana Brenis is a Research Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory (UKTPO) at the University of Sussex Business School. She holds an MSc in Business, Finance and Economics and a PhD in Economics from the University of Sheffield. Adriana’s research focuses on international trade, economic policy analysis and innovation.

The UK government recently announced its plan to implement common user charges for imports coming into the country. This has generated some controversy and, just this week, rumours that the government may again suspend the introduction of elements of the new Border Target Operating Model (BTOM).

The common user charges, set at a flat rate of £10 or £29 per commodity line, are capped at 5 charges per consignment, resulting in a maximum fee of £145. These charges will be applied to low-risk products of animal products (POAO), medium and high-risk animal products, along with plants and plant products. Initially, they will only be collected at border controls in Dover and Eurotunnel starting April 30th. This is part of the new BTOM system, aimed at improving border procedures. The goal is to cover the expenses of running these border facilities while protecting the UK’s food supply, farmers and the environment from diseases that could come in through these routes.

This blog explores the significance of these ports in facilitating the importation of goods into the UK and examines the extent to which the announced charges may affect incoming shipments.

Our calculations suggest that the animal and plant products that could face common charges represent about £38 billion of imports into the UK, making up 6% of all UK imports. Among these, 5.8% represent animal products and 0.2% plant products. Table 1 shows that 78% of these ‘at risk’ imports come from the EU, while 22% are from other parts of the world.

| Products at risk | EU | Non – EU | Total |

| Animal | 28.68 | 8.18 | 36.86 |

| Plants | 1.22 | 0.24 | 1.46 |

| Total | 29.90 | 8.41 | 38.32 |

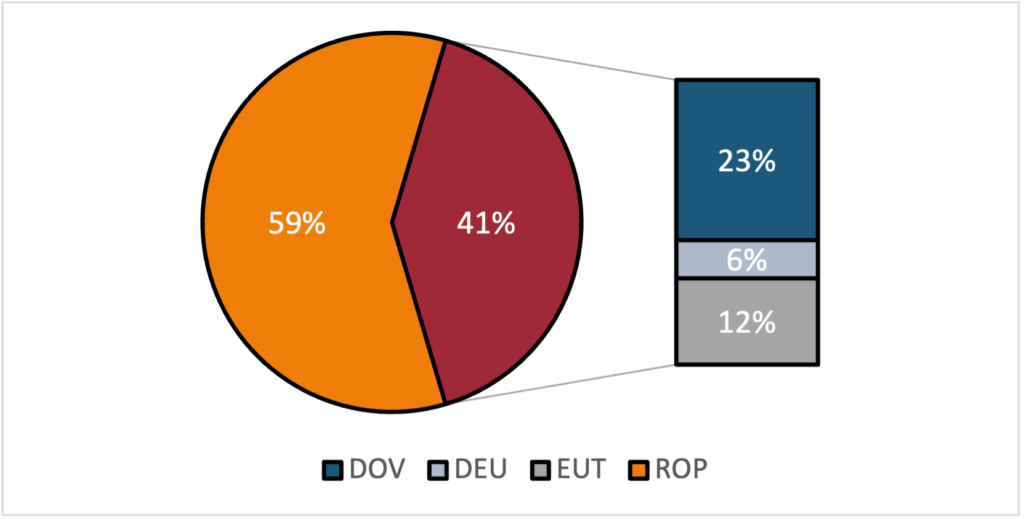

Given the substantial proportion of animal imports from the EU, we examine what share passes through the controlled borders – where the common user charges will be implemented starting April 30th. As illustrated in Figure 1, of the eligible animal products subject to charges (£28.7 billion), 41% (£11.7 billion) are imported through the controlled borders of Dover (DOV), Eurotunnel (EUT), and Dover/Eurotunnel (DEU), while the remaining 59% come through other ports in the UK (ROP). Among these, Dover stands out as the primary port for imports at 23%, followed by 12% via Eurotunnel, and 6% through Dover/Eurotunnel.

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

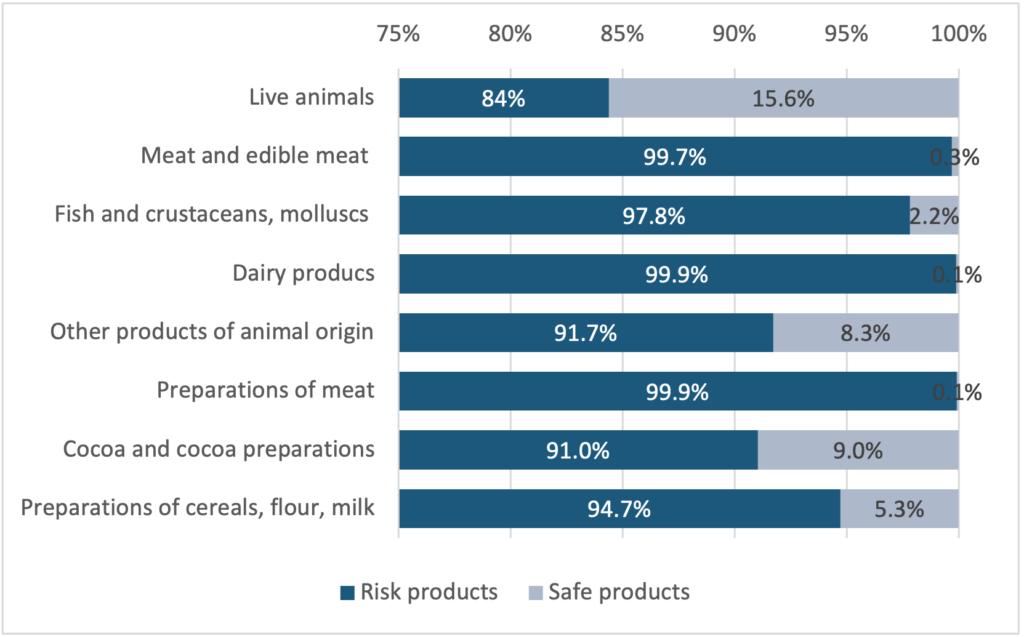

Among the different types of animal products classified under the Harmonized System (HS) at the 2-digit level, 31 out of the total number of 97 HS chapters have a percentage of animal products that could be subject to charges. Figure 2 highlights the HS classification at a 2-digit level, with the highest percentage of imported animal products at risk. Particularly, almost all imported products in HS 02 “Meat and edible meat”, HS 04 “Dairy products”, and HS 16 “Preparations of meat” are at risk. Other sections with more than half of their imported products at risk include HS 21 “miscellaneous edible preparations” (73%), and HS 23 “Residues and waste from the food industry” (75%). In addition, 91% of imported products in HS 18 “Cocoa and cocoa preparations” and 95% in HS 19 “Preparations of cereals, flour, starch or milk” could face charges, depending on whether they contain products of animal origin (POAO).

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

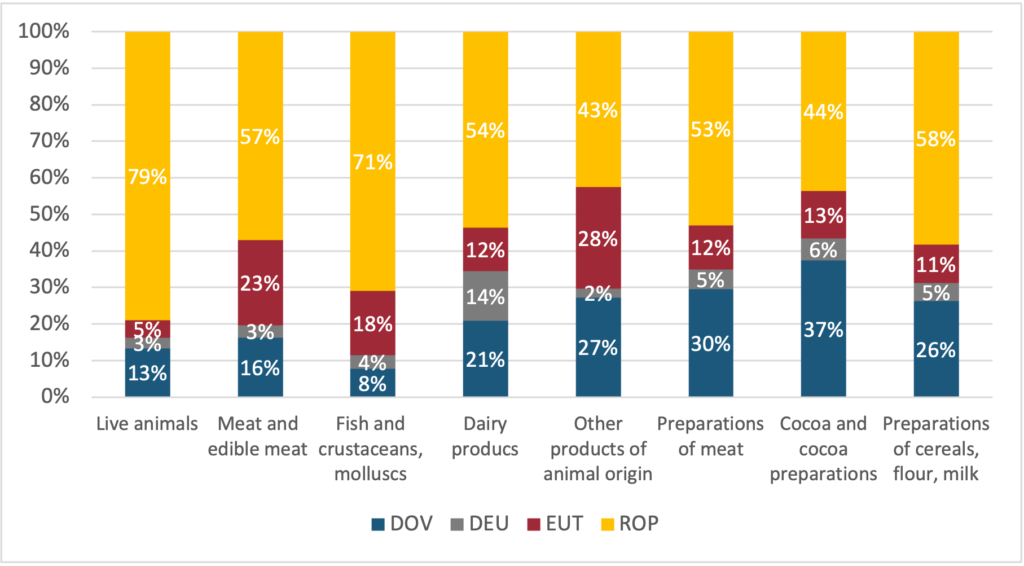

Focusing on the eight sections where most imports face potential fees, Figure 3 illustrates the share of the imports coming through the ports where charges apply. Live animals and fish, crustaceans and molluscs mainly come through other ports (79% and 71% respectively). In contrast, other products of animal origin primarily come through fee-charging ports, with Eurotunnel (EUT) at 28%, and Dover (DOV) at 27%. Similarly, cocoa and cocoa preparations products mostly enter through ports with charges, with 37% through Dover. Moreover, a large proportion of meat and edible meat (43%), dairy products (46%), preparations of meat (47%), and preparation of cereals, flour, and milk (42%) are brought in through these controlled borders with fees.

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

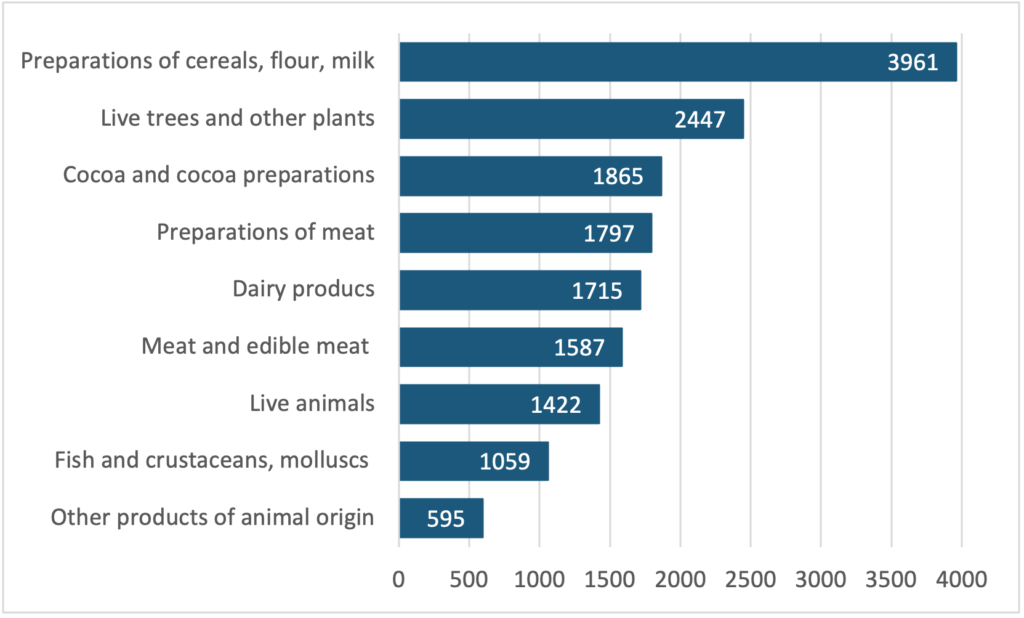

In 2023, out of the total Great Britain firms importing products globally (248,445 firms), those importing goods at risk from both EU and non-EU countries accounted for 16%, totalling 40,619 firms. Figure 4 provides the number of firms primarily importing within these eight categories, along with plant products from both EU and non-EU countries. The figure shows a significant number of firms fall within preparations of cereals, flour, and milk, followed by live trees and cocoa and cocoa preparations. As seen in Figure 3, these two categories – cocoa and cocoa preparations, as well as preparations of cereals – show a considerable percentage of imports arriving through the charged ports of Eurotunnel and Dover. Consequently, many of these firms could be affected by the upcoming common user charges starting on April 30th.

Table 2 provides a detailed view of the number of firms importing large amounts of animal and plant products within these categories. Considering the sections with high percentages of animal imports arriving through charged ports, like other products of animal origin and cocoa preparations, along with those with substantial imports (such as meat, dairy, and cereal preparations) are also, products like animal products n.e.s, including fresh cheese, pizzas, chocolate and other cocoa preparations, and sausages, which could be among the most affected.

Source: HMRC and Animal & Plant Health Agency (2023)

| 8-digi level | Name | Number of Firms |

| 01012100 | Pure-bred breeding horses | 859 |

| 02013000 | Fresh or chilled bovine meat, boneless | 390 |

| 03047190 | Frozen fillets of cod “Gadus morhua, Gadus ogac” | 101 |

| 04061050 | Fresh cheese “unripened or uncured cheese”, incl. whey cheese and curd | 258 |

| 05119985 | Animal products, n.e.s.; dead animals, unfit for human consumption | 351 |

| 06029050 | Live outdoor plants, incl. their roots | 761 |

| 16010099 | Sausages and similar products of meat | 609 |

| 18063100 | Chocolate and other preparations containing cocoa | 368 |

| 19059080 | Pizzas, quiches and other bakers’ wares | 1370 |

The introduction of common user charges for imports (especially for firms dealing with products subject to these fees) could have significant implications for both businesses and consumers. For firms, particularly those importing goods through charged ports, there may be a notable increase in operational costs due to the additional charges incurred. This could potentially impact their profitability and competitiveness. Additionally, firms may need to reevaluate their supply chain strategies, potentially exploring alternative ports or sourcing options to mitigate the impact of fees. Furthermore, the rise in costs could prompt changes in consumer behaviour, with some individuals opting for alternative imported products not subject to fees. Overall, the implementation of common user charges has the potential to reshape import dynamics, affecting both firms and consumers alike.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher April 23rd, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

4 January 2024

Guest author David Henig is Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE). He has written extensively on the development of UK Trade Policy post Brexit, in the context of developments in EU and global trade policy on which he also researches and writes.

There was relief for Europe’s automotive sector at the start of December when the UK and EU agreed to maintain current product specific rules of origin for electric vehicles within the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) until the end of 2026. A scheduled intermediate stage of tightening on the way to even more stringent final rules to take effect from January 2027 was abandoned. Industry in both the UK and EU had been warning of potential 10% tariffs without an agreement and welcomed the move.

At the most basic level, this extension demonstrated that the UK and EU can find ways to improve their trading relationship. This had previously been shown with the agreement of the Windsor Framework to supplement the Northern Ireland Protocol to the Withdrawal Agreement, reached in February 2023, as well as full UK accession to the Horizon science research programme, scheduled to take effect at the start of 2024. Many commentators on both sides had doubted such progress would be possible at the start of the 2023.

With the TCA being the most valuable preferential trade arrangement to both the UK and EU, any indications of a better relationship should come as a relief. According to a November European Commission report “on the Implementation and Enforcement of EU Trade Policy”, in terms of EU preferential trade deals 22.5% of their value in goods is with the UK, rising to 46% for services. Meanwhile, despite the UK government’s aspirations for Global Britain, over 40% of its total trade remains with the EU.

Details of the negotiation and agreement over electric vehicles suggest however that it would be premature to expect plain sailing from this point onwards. There were suggestions in October that the broad principles of an extension for electric vehicles had been agreed, yet there were concerns on the EU side about whether this should be done legally inside the TCA or through a separate instrument. Final text which includes a prohibition of further extension showed a certain sensitivity in Brussels. In time this restriction could itself by renegotiated, but a marker not to do so has been laid.

For the EU, sensitivity is almost certainly based on their continued fears of a Brexit UK still expecting the market access of a Member State, in particular in areas of its specific interest. Experience was further that this attitude came with petulance and aggression from UK negotiators when not granted, in public and possibly to a degree inside negotiating rooms. These fears and memories should be of particular concern to a Labour Party committed to seeking TCA enhancements, particularly in terms of mutual recognition through agreements on food and drink, and professional qualifications. While the EU has shown a willingness to talk and does have its own interests, it should be obvious that no deal will be straightforward particularly if the EU is concerned about protection against future UK governments.

Meanwhile UK and EU automotive sectors face the challenge of being some way behind their Chinese competitors. For the time being, with this extension, and with the EU’s investigation into subsidies that may lead to countervailing duties, the industry is being given some time to catch up. There is clearly the expectation of this happening in the next three years, something which industry experts are already suggesting to be optimistic.

Extending and changing preferential trade agreements is never an easy matter, even between the friendliest trade partners. Particular circumstances of the UK-EU relationship make this even more difficult. Given such a background, one should probably see progress this year including on electric vehicles as being as good as it could get. That can perhaps be the foundation for a new approach, in a new year, and possibly even a new UK government, but they would do well to take nothing for granted.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher January 4th, 2024

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 13 December 2023

13 December 2023

James Harrison is Professor in the School of Law at the University of Warwick. Emily Lydgate is Professor in Environmental Law at the University of Sussex and Deputy Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory (UKTPO). Ioannis Papadakis is a researcher at the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Research Fellow in Economics. Sunayana Sasmal currently serves as a Research Fellow in International Trade Law at the UKTPO. Mattia di Ubaldo is Fellow of the UKTPO and Research Fellow in Economics of European Trade Policies. L. Alan Winters is Founding Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex.

In answering this important question, different disciplinary approaches have emerged as have a range of different and sometimes contradictory findings. At the moment, scholars from the different disciplines are not talking to each other about the implications of this. The authors of this blog suggest it is vitally important that they begin to do so.

Trade agreements around the world increasingly include environmental and labour provisions. Their presence attests to policymakers’ recognition that trade agreements cannot simply focus on economic issues. They should also address environmental and social concerns. But the existence of these provisions on paper is not itself a cause for celebration. Such provisions are only meaningful if they have positive outcomes in reality – if they, for instance, lead to decreased carbon emissions or enhanced conditions for workers.

Different methodological approaches to researching this issue have come to different conclusions about their real-world impact. First, quantitative studies, largely undertaken by economists, have tended to identify significant and generalised positive impacts for at least some provisions.

On the environmental side, one early influential study found that EU FTAs with environmental provisions improve environmental conditions in countries with strong civil societies. It also concluded that US FTAs are effective during the negotiation period in improving the environmental policy environment of partner countries. Another, covering 680 PTAs with environmental provisions, found that environmental provisions can help reduce dirty exports and increase green exports from developing countries.

In relation to labour provisions, one study found that the likelihood of a state fully protecting workers’ rights rises by 10% once it has signed an FTA with the EU which contains labour provisions. Another study found that labour provisions had a positive impact on (particularly female) labour force participation rates (although not on other labour rights).

On the other hand, more recent work, carried out with more advanced statistical techniques and more granular data on both the content of FTAs and the environmental outcomes, tends to find only mixed evidence: some specific provisions on greenhouse gases appear to be effective, but results are not consistent across models. No significant effects are found for labour provisions. Some recent work has also focused on specific outcomes produced by environmental provisions. Thus, one study, focused on deforestation, found that environmental provisions are effective in limiting deforestation following the entry into force of FTAs, but only because FTAs without such provisions increase deforestation and the provisions offset this.

There is also some indirect evidence of the effects of FTAs. One study suggests a positive relationship between domestic environmental legislation (not environmental outcomes) and preferential trade agreements with environmental provisions, while another finds that FDI is deterred if FTA labour and environmental provisions have a higher degree of legalization. However, others suggest that such provisions might increase the costs of trade and production.

To sum up this first side of the literature, quantitative studies tend to suggest that some generalisable, although often limited, effects can be ascribed to labour and environmental provisions in FTAs. Across a wide range of different agreements, these studies suggest that some changes will happen as a result of the presence of some types of provisions – for instance that deforestation will be limited or domestic environmental legislation will be signed.

Legal scholars are often puzzled by these results. Environmental and labour provisions take multiple forms in different FTAs and are often not the kind of binding and enforceable provisions that are expected to produce significant results. In high-level summary, trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters (as found in EU FTAs) and equivalent provisions in other FTAs often consist of ‘best endeavours’ clauses that commit parties to work towards high standards; cooperation on thematic issues, including through upholding agreements such as conventions of the International Labour Organization or the Paris Agreement; and obligations not to reduce levels of protection, often described as non-regression clauses.

Much debate has focused on whether these non-regression clauses should be tied to sanctions, as the US has done, and more recently the UK, Australia and New Zealand. In contrast, EU FTA commitments emphasize implementation through stakeholder dialogue of bespoke committees, such as a Civil Society Forum and Domestic Advisory Group. The EU has unveiled a plan for a limited increase in the use of sanctions in TSD chapter enforcement, and the USMCA has introduced new and innovative forms of labour rights enforcement.

Enforcement mechanisms remain an important focus for legal scholarship, as does the influence of FTA negotiations in changing domestic environmental and labour laws. However, focusing solely on treaty texts and the strength of the bodies that potentially enforce them, doesn’t provide a full account of the impacts of particular provisions.

Qualitative studies have been used by political scientists, geographers, business and socio-legal scholars to attempt to understand how obligations contained in treaty texts have translated into changes in labour and environmental outcomes. Such studies have generally involved case study methodologies and techniques such as in-depth interviews, focus groups and participant observation that allow deep exploration of the causal effects of certain sustainability provisions.

Most of the detailed studies have focused on EU trade and sustainable development (TSD) chapters and the labour standards provisions therein – although as environmental provisions are implemented and enforced in the same way, there are some learnings from these studies on the environmental side. Case studies on impacts in the EU’s FTAs with the CARIFORUM countries, Colombia, Korea, Moldova and Peru have found little or no evidence that the existence of TSD chapters led to improvements in labour standards governance, nor that there were significant prospects for longer-term change. Less robust studies of labour standards provisions in individual US agreements have led to similar conclusions. Positive impacts have been found to occur only in very limited scenarios when accompanied by specific actions by key actors (government officials, civil society actors, trade unions etc.), in relation to specific trade agreements where those issues became politically contentious, such as prior to the ratification of the EU-Vietnam FTA.

Overall, the findings of the studies presented here are very different. But their methodological strengths and weaknesses can also be contrasted. Quantitative studies are able to consider labour and environmental provisions across a wide range of agreements, thereby providing information about general tendencies. But these studies, particularly the earlier ones, are less compelling on the issue of causality. While sustainability provisions are posited as a likely cause of improvements in environmental and labour protection, there are generally weak attempts to substantiate causal links. The few studies that do make serious efforts to identify causal (and unbiased) links, tend to come up with many fewer positive effects. Most importantly, however, they all lack a convincing narrative about the mechanisms leading from FTA provisions to impacts on the ground.

Qualitative studies take causality seriously and can give detailed answers on the direct causal questions of how and why sustainability provisions have or do not have effects. On the other hand, they are weaker when it comes to generalisability; reliance on individual case studies leaves qualitative studies open to accusations that they have missed the ‘bigger picture’.

Scholars who have adopted these different approaches should come together to try to understand the rationale for these different findings and to promote better understanding of their respective research methods. Drafting this blog challenged some of our assumptions about how different disciplines tackle research questions, and facilitated our understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of our research approaches.

But this is not only an academic question. Understanding these methodological strengths and weaknesses has implications for policy making, as correct and full facts are essential to make good policy. For instance, there are policies with unintended consequences that can be identified by talking to people. When these are not considered, empirical analysis may lead to misleading policy prescriptions, even if the effects it estimates are precise, causal and generalisable.

Policymakers need to understand the effects of labour and environmental provisions if they are to take the right kinds of actions to promote better social and environmental outcomes through trade agreements. The authors of this blog all agree that there is a big difference between (1) telling policymakers they can achieve meaningful change through inserting environmental or labour provisions into trade agreements and (2) that to be effective, they must think very carefully about both the design of those provisions and how they will be taken up and utilised by key actors thereafter.

A broad account of how the disciplines can work together might go something like this: Economic studies identify FTAs where the correlation between environmental or labour provisions and positive outcomes appears to be high. Legal scholars bring a detailed understanding of the typology of FTA environmental and social provisions within these FTAs, using this to further refine economists’ findings about causal mechanisms. Political scientists, geographers, business, and socio-legal scholars interrogate how issues such as relationships, power asymmetries, access to information and access to resources shape the effectiveness of the environmental and social provisions in practice.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher December 13th, 2023

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Environment, environmental law, EU, FTAs, labour standards, Trade agreements, trade policy

20 October 2023

Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. She was the Special Adviser to the House of Lords Internal Market Sub-Committee in respect of its inquiry into Brexit: competition and state aid, and has previously acted as a consultant to the European Commission. She specialises in EU economic law. She is currently working with the European Judicial Training Network on developing training courses for national judges in EU competition law.

Erika Szyszczak is a Professor Emerita and a Fellow of the UKTPO. She was the Special Adviser to the House of Lords Internal Market Sub-Committee in respect of its inquiry into Brexit: competition and state aid, and has previously acted as a consultant to the European Commission. She specialises in EU economic law. She is currently working with the European Judicial Training Network on developing training courses for national judges in EU competition law.

On 3 October 2023 the Council and the European Parliament reached provisional political agreement on an Anti-Coercion Instrument (ACI).[1] It is the latest legal trade measure contributing to the developing economic statecraft of the EU as part of the Open Strategic Autonomy. The tipping point for the EU to consider an extra method to address trade distortion occurred when China imposed trade restrictions on Lithuania after Lithuania improved trade relations with Taiwan. Lithuanian companies found that they could not renew or conclude contracts with Chinese firms, shipments were not being cleared and customs paperwork was held up. The ACI is portrayed as a deterrent device, discouraging third states from targeting the EU and its Member States with economic coercion through measures affecting trade or investment. It is another example of how the EU is forging a leadership role in developing new economic trade rules in a fragmented global trading world, by stealing a lead in the narrative on what is, and what is not, acceptable trade policy.

The European Commission proposed the ACI in the form of a Regulation on 8 December 2021 at the request of the Council and the European Parliament. The European Parliament Committee on International Trade adopted amendments to the proposal on 10 October 2022, and in the plenary session confirmed the Parliament’s negotiating mandate on 19 October 2022. The Council agreed its negotiating position on 16 November 2022.

The tipping point for the EU to consider an extra method to address trade distortion occurred when China imposed trade restrictions on Lithuania after Lithuania improved trade relations with Taiwan. Lithuanian companies found that they could not renew or conclude contracts with Chinese firms, shipments were not being cleared and customs paperwork was held up.

The Legal Base for the ACI is Article 207(2) TFEU:

“The European Parliament and the Council, acting by means of regulations in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, shall adopt the measures defining the framework for implementing the common commercial policy.”

This is trade legal base for a measure designed to enhance EU economic and political resilience. The European Parliament Committee on International Trade adopted amendments to the proposal on 10 October 2022, and in the plenary session confirmed the Parliament’s negotiating mandate on 19 October 2022. The Council agreed its negotiating position on 16 November 2022.

The ACI defines economic coercion as when a non-EU country attempts to pressure the EU or a Member State into making a specific choice by applying, or threatening to apply, trade or investment measures. In the European Parliament Briefing ‘Proposed anti-coercion instrument’ different types of economic coercion are identified:

Once notified of an alleged act of economic coercion the European Commission must investigate within 4 months. The European Commission report will be sent to the Council which then has between 8 to 10 weeks to decide, by a qualified majority vote, whether the complaint of economic coercion exists. The first response will be to engage in dialogue to persuade the authorities of the non-EU country to stop the acts of economic coercion. If diplomacy fails, the EU has a range of countermeasures it can apply with the consent of its Member States. These include restrictions in trade of goods and services, intellectual property rights and foreign direct investment, imposing constraints on access to the EU public procurement market, capital market, and authorisation of products under chemical and sanitary rules. The European Commission has 6 months to set out the appropriate responses, whilst keeping the European Parliament and the Council informed at all stages.

The ACI is a new legal development in international trade law. It has been developed in response to activities deployed by China and the US which threaten EU security. The ACI is another example of how the UK, post-Brexit, may be the target of EU trade defence instruments.

Why does the EU need the ACI? The European Commission justifies the measure by arguing that new forms of economic coercion are not addressed by the existing conventional trade defence measures of the EU (for e.g. anti-dumping).

The concept of economic coercion set out in the ACI is not caught by current WTO rules. Even if the threatening behaviour could be brought within the existing WTO agreement, the stymied appellate process makes enforcement difficult.

However, the ACI is not a rapid defence trade mechanism. In fact, an EU firm or sector could suffer irreparable damage in the time it takes to activate and use the ACI. It may also encourage third countries to develop their own trade defence tools which are more effective than the ACI in responding to escalating situations.

[1] The European Commission proposed the ACI in the form of a Regulation on 8 December 2021 at the request of the Council and the European Parliament. EUR-Lex – 52021PC0775 – EN – EUR-Lex (europa.eu). The European Parliament Committee on International Trade adopted amendments to the proposal on 10 October 2022, and in the plenary session confirmed the Parliament’s negotiating mandate on 19 October 2022. Procedure File: 2021/0406(COD) | Legislative Observatory | European Parliament (europa.eu). The Council agreed its negotiating position on 16 November 2022. pdf (europa.eu). The Legal Base for the ACI is Article 207(2) TFEU: The European Parliament and the Council, acting by means of regulations in accordance with the ordinary legislative procedure, shall adopt the measures defining the framework for implementing the common commercial policy.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher October 20th, 2023

Posted In: Uncategorised

22 September 2023.

L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP), Professor of Economics at University of Sussex Business School and Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

When UK Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, spoke on climate policy on 20th September and talked the following day to the BBC’s Today programme, he did much more than delay the UK’s policies for achieving net zero. He said he was changing the terms of political debate. He spoke of honesty, pragmatism, transparency, and ‘getting opinions and advice from anybody’. Nothing could be more welcome to anybody who has engaged with UK policy over the last eight years, during which the greatest failing has been the lack of these characteristics at the highest political levels.

I would like to celebrate the change in practice immediately, so let me pose a few straightforward questions to Mr Sunak to which a pragmatic government must surely have answers already.

Let me start with the climate policy announcements themselves:

What are the estimates of how much his new climate policies will increase the UK’s total carbon dioxide emissions between now and 2050?

What are the estimates of how much the new measures will reduce the expenditure by the average household over the period 2023 to 2035?

Nearly all experts believe that the more rapid a country’s adjustment towards net zero, the greater the costs it faces. Does Mr Sunak agree? What estimates does he have of the increased adjustment costs of reaching net zero in 2050 arising from the new delays?

Will the new policy on energy infrastructure be fully costed and have a timescale that the people who have to deliver it on the ground believe is credible? When is it due and when it is announced will My Sunak commit that his government(s) will never change it?

Next, let me turn to Brexit and international trade policy – the focus of both The Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy and the UK Trade Policy Observatory. We are particularly pleased to see Mr Sunak speaking about imposing ‘costs on working people, especially those who are already struggling to make ends meet and to interfere so much in people’s way of life without a properly informed national debate’, which has been of particular concern to us.

Is Brexit working for the British economy? And, as we say in university exams, explain your reasoning.

Does Mr Sunak really believe that the additional bureaucratic costs of importing food into the UK (nearly all of which comes from the European Union) has had no effect on food prices?

Is the UK actually going to introduce customs formalities on imports from the EU or is it just going to give up controlling that border? Given that we have had multiple postponements of the introduction, a simple ‘yes’ will not suffice.

How many UK firms have stopped exporting to the EU since 2020? And how many of them have started exporting elsewhere?

What is the cause of UK business investment more or less flatlining since 2016?

What is the main reason given by British business for its lack of enthusiasm about UK regulations diverging from those of the EU?

How much will it cost the UK chemicals industry to obtain regulatory approval under UK REACH?

With the World Trade Organization’s dispute settlement system broken, why will the UK not join 26 other WTO members in the temporary alternative mechanism for resolving trade disputes – the Multi-Party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA)?

Does Mr Sunak really want independent advice on trade policy? His government proposed in March to neuter the independent Trade Remedies Authority. No action has been taken since. May we give him credit for changing his mind?

Big changes in political practice are hard to engineer, so perhaps Mr Sunak can underpin his revolution by committing that pigs will not fly between now and the next general election.

This blog was first published on the CITP website on September 22, 2023.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher September 22nd, 2023

Posted In: Uncategorised

June 21 2023

Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Guillermo Larbalestier is Research Assistant in International Trade at the University of Sussex and Fellow of the UKTPO.

This is an extract from a paper first published on The Review Of European Law journal on may 5, 2023. To read it in its entirety, click here.

In the extract below we suggest that there are few trade benefits to be had. Is there something else that enhances economic viability? Is it as “regulatory sandboxes”? The present regulations require adherence to international environmental and financial standards. So what about R&D? There are some wind turbine, carbon capture and “Green Hydrogen” projects but not much linkage to Freeports. We don’t address the recent accusations of financial irregularities, yet clearly, property speculation is the other way to profit. (more…)

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 21st, 2023

Posted In: UK- EU

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 16 June 2023

16 June 2023

Chloe Anthony, Doctoral Researcher at University of Sussex Law School and Legal Researcher for the UK Environmental Law Association’s Governance and Devolution Group.

Chloe Anthony, Doctoral Researcher at University of Sussex Law School and Legal Researcher for the UK Environmental Law Association’s Governance and Devolution Group.

The Retained EU Law (Revocation and Reform) Bill is part of the Government’s ‘Brexit opportunities’ agenda. It is currently in its final stages in Parliament, going back and forth between the Houses, in a debate on the inclusion of clauses that aim to safeguard parliamentary scrutiny and prevent the lowering of environmental protections. It returns to the Commons on 20 June. (more…)

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 16th, 2023

Posted In: UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, Environment, EU, Europe, food, Single Market, TCA, Trade and Cooperation Agreement, trade policy, UK economy

8 June 2023

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Manuel Tong Koecklin is a Research Fellow in the Economics of Trade at the UK Trade Policy Observatory and University of Sussex Business School.

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Manuel Tong Koecklin is a Research Fellow in the Economics of Trade at the UK Trade Policy Observatory and University of Sussex Business School.

Recently, there have been a series of reports in the media focussing on the challenges that electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers are likely to face, from the end of this year, in exporting electric vehicles tariff-free to the EU. The concern it because of the changes in the rules of origin (ROOs) requirements (for EVs and batteries) which will become more difficult from January 2024, and again from 2027 and 2028 onwards. (more…)

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 8th, 2023

Posted In: UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, EU, Europe, goods, Single Market, TCA, Trade and Cooperation Agreement, trade policy, UK economy

19 May 2023

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Nicolo Tamberi is Research Officer in Economics at the University of Sussex and Fellow of UKTPO.

Michael Gasiorek is Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Co-Director of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy. He is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex Business School. Nicolo Tamberi is Research Officer in Economics at the University of Sussex and Fellow of UKTPO.

Earlier this week Vauxhall announced it may withdraw from producing electric vehicles in the UK owing to difficulties from meeting ‘rules of origin’ on EU exports. The car manufacturer called for a revision to the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) between the EU and then UK, notably regarding rules of origin (ROOs). Ford and Jaguar Land-Rover have also warned of the difficulties and called for a revision to the TCA and German producers have also expressed concerns about the meeting these ROOs. (more…)

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher May 19th, 2023

Posted In: UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, EU, EU Single Market, Europe, goods, TCA, Trade and Cooperation Agreement, trade policy, UK economy