Briefing Paper 81 – June 2024

Michael Gasiorek, Justyna A. Robinson, Rhys Sandow

Results of responses to the LPF questions

Policy formulation is complex. To some extent this is because most policy options are complicated, but also because politicians need to consider how the policies will land with their voters. Increasingly, too, there is pressure in the making of policies to ensure that there is ‘appropriate consultation’ particularly with those who may be affected by the policy. In turn, how to do and use consultative processes is not straightforward. To put it simply: hypothetically you could ask 100 people their views on a topic, get 100 different responses, choose the responses you wanted in the first place, and then claim that you undertook appropriate consultation. You could also get five very long detailed responses, and 95 short one-sentence responses, so there needs to be a way to balance such variety.

In this Briefing Paper we assess the views expressed by those who responded to the Labour Party’s 2023 national consultation on UK trade policy. Given the forthcoming general election such an analysis is very timely. To date, and with the general election just over four weeks away, there has been a disappointing amount of discussion by the main political parties on international trade and trade policy. In fact, there has been no discussion other than in the recently released manifestos, and this is interesting. Focussing on the two main parties, clearly both the Conservative and the Labour party have a range of views on trade. This can be seen in their current manifestos[1] and in those from the 2019 election campaign. In 2019, the Conservatives talked about negotiating a free trade agreement with the EU, freeports, and the aim for 80% of UK trade to be covered by free trade agreements within three years. Labour talked about a better Brexit deal and closer alignment with the EU, and the importance of trade deals upholding standards regarding the climate, environment, food and agriculture, as well as labour standards. In the Labour Party recently released manifesto we again see discussion of a closer relationship with the EU, a desire for ‘targeted’ new free trade agreements, and stand-alone sectoral deals, a role for multilateral cooperation and the promotion of high food standards.

In 2023 the Labour Party engaged in a National Policy Forum consultation on a range of themes which were open both to Labour party members and the general public[2]. The aim of the Forum was to collate views to inform the formation of Labour Party policy. One of the themes focused on “Britain in the World”, and within that, there were specifically seven questions concerning international trade. These were:

In this Briefing Paper, we analyse the responses to the Labour Party’s 2023 National Policy Forum consultation on what was called ‘progressive trade policy’. In addition to the difficulties outlined earlier regarding the use of consultative processes, it is also necessary to decide how to undertake the analysis of the responses received. Advances in computational techniques increasingly allow for more sophisticated analyses of texts than was previously possible. In this briefing paper, we use corpus linguistic techniques (McEnery & Hardie 2011; Kilgarriff et al. 2014) together with close reading to analyse the responses. There were 302 written responses to the Labour Policy Forum (hereafter, LPF), split between Labour Party members and non-members, such as businesses or charities, totalling 244,894 words. We identify the key themes within the responses both overall and in relation to each of the seven questions that the respondents were asked.

First, in Section 2, we present the overview of the themes that stand out across the entire set of responses; before outlining the key issues respondents raised in relation to each of the seven questions in Section 2. In the final section we reflect on the interface between these responses and the Labour Party 2024 manifesto.

In this section we provide an overview of the key themes captured across all of the responses to the LPF. First, and to assess what the respondents thought regarding overall priorities, we identify which activities/outcomes they think should be either promoted or reduced. In practise, we contrast the types of grammatical objects the verbs to promote and to reduce take. Figure 1 presents objects of verbs to promote and to reduce according to the typicality score[3]of each collocation.[4] The further a word is to the left of the figure, the stronger its collocation with to reduce, while greater proximity to the right demonstrates a stronger collocation with to promote. Hence, we see that respondents feel principally that trade policy should aim to reduce inequality, poverty and emissions, while it should promote economic growth, rights, and values.

Figure 1: Objects of verbs to promote and to reduce in LPF responses.

The analysis also includes less frequent terms that did not meet the frequency threshold for the figure, but nonetheless speak to themes in the responses. In the lists below we consider other emerging issues. One the one hand, respondents wish trade policy to promote the following areas, i.e.

On the other hand, respondents wish trade policy to reduce problems associated with the following areas, i.e.

Another approach to identifying key concerns, is to compare the frequency of words/terms used in the responses relative to a baseline measure.[5] Hence, in Table 1 we see that environmental appears top of the list – this is because that word (including variants) appeared more significantly in the consultation responses than would be expected from its use in the baseline. We identified 300 most distinctive words and phrases (measured by something called the LogDice score), relative to the baseline. We then order the results on the Average Reduced Frequency (ARF). The ARF is a measure which essentially rebalances the frequency by considering how many documents the term appears in, and how often it may appear in a single document[6]. This ensures the data is not skewed by a small number of responses that frequently use particular words/phrases. For completeness, we also present the data for the raw frequency and the frequency of documents in which the word/phrase occurs (DOCF).

Tables 1 and 2 present the top 20 words and phrases, respectively, that are used both frequently and widely in the responses to the LPF, and which help us identify the most salient themes in the data[7].

Table 1: The top 20 most common words in the 2023 Labour Policy Forum responses, in relation to a baseline

|

Rank |

Item |

Frequency |

DOCF |

ARF |

|

1 |

environmental |

452 |

97 |

175.4 |

|

2 |

EU |

494 |

118 |

175.0 |

|

3 |

chain |

445 |

84 |

162.8 |

|

4 |

climate |

406 |

81 |

143.7 |

|

5 |

sustainable |

224 |

66 |

96.0 |

|

6 |

consultation |

132 |

72 |

66.4 |

|

7 |

poverty |

153 |

46 |

54.6 |

|

8 |

rights |

138 |

32 |

42.1 |

|

9 |

Brexit |

99 |

58 |

41.8 |

|

10 |

transparency |

91 |

38 |

39.9 |

|

11 |

inequality |

106 |

37 |

38.6 |

|

12 |

resilience |

103 |

38 |

38.3 |

|

13 |

devolve |

88 |

34 |

31.5 |

|

14 |

diligence |

144 |

17 |

28.7 |

|

15 |

ftas |

92 |

24 |

28.1 |

|

16 |

wto |

85 |

25 |

27.5 |

|

17 |

multilateral |

56 |

28 |

27.4 |

|

18 |

scrutiny |

61 |

27 |

24.8 |

|

19 |

fossil |

111 |

21 |

23.8 |

|

20 |

Equitable |

37 |

20 |

16.9 |

Table 2: The top 20 most common phrases in the 2023 Labour Policy Forum responses, in relation to a baseline

|

Rank |

Item |

Frequency |

DOCF |

ARF |

|

1 |

human right |

605 |

84 |

184.8 |

|

2 |

supply chain |

357 |

80 |

132.4 |

|

3 |

trade agreement |

236 |

58 |

87.2 |

|

4 |

trade deal |

185 |

58 |

69.1 |

|

5 |

economic growth |

84 |

47 |

41.3 |

|

6 |

international development |

91 |

33 |

34.8 |

|

7 |

due diligence |

142 |

17 |

28.4 |

|

8 |

workers” right |

61 |

30 |

27.9 |

|

9 |

developing country |

68 |

27 |

27.5 |

|

10 |

environmental standard |

64 |

30 |

24.8 |

|

11 |

net zero |

51 |

30 |

24.5 |

|

12 |

global supply chain |

40 |

24 |

23.1 |

|

13 |

fossil fuel |

108 |

19 |

21.6 |

|

14 |

value chain |

64 |

18 |

20.8 |

|

15 |

development goal |

40 |

22 |

19.3 |

|

16 |

environmental protection |

36 |

26 |

18.6 |

|

17 |

free trade |

40 |

20 |

18.4 |

|

18 |

trade strategy |

43 |

16 |

15.7 |

|

19 |

animal welfare |

54 |

18 |

15.2 |

|

20 |

impact assessment |

40 |

15 |

15.1 |

Clearly, some of the terms in Tables 1 and 2 are a function of the wording of the seven questions in the LPF (e.g. resilience and to devolve), others speak to the key issues that the respondents raise in their responses. There are five key themes which emerge. These are concerned with the following areas WELFARE AND RIGHTS, THE ENVIRONMENT, SUPPLY CHAINS, (FREE) TRADE AGREEMENTS, and the PROCESSES underpinning the negotiation of trade deals. The theme of WELFARE AND RIGHTS is evident through human rights, animal welfare, workers’ right, and rights. Terms environmental standard, net zero, environmental protection, environmental, climate, and fossil illustrate the ENVIRONMENT theme. The theme of SUPPLY CHAINS is evident through terms global supply chain, value chains, chain, sustainable, and resilience. The theme of (FREE) TRADE AGREEMENTS is exemplified by terms trade agreement, trade deal, free trade, EU, Brexit, and ftas [free trade agreements]. Lastly, the terms impact assessment, consultation, transparency, to devolve, and scrutiny speak to the theme of processes of trade deals.

We discuss SUPPLY CHAINS in the overview of Question 3, which addresses this topic specifically. Likewise, we consider WELFARE AND RIGHTS specifically in our analysis of Question 4. We also discuss PROCESSES of trade deals with reference to Questions 2 and 7. In the current section, we consider the way in which LPF respondents conceptualise the issues of (FREE) TRADE AGREEMENTS and the ENVIRONMENT.

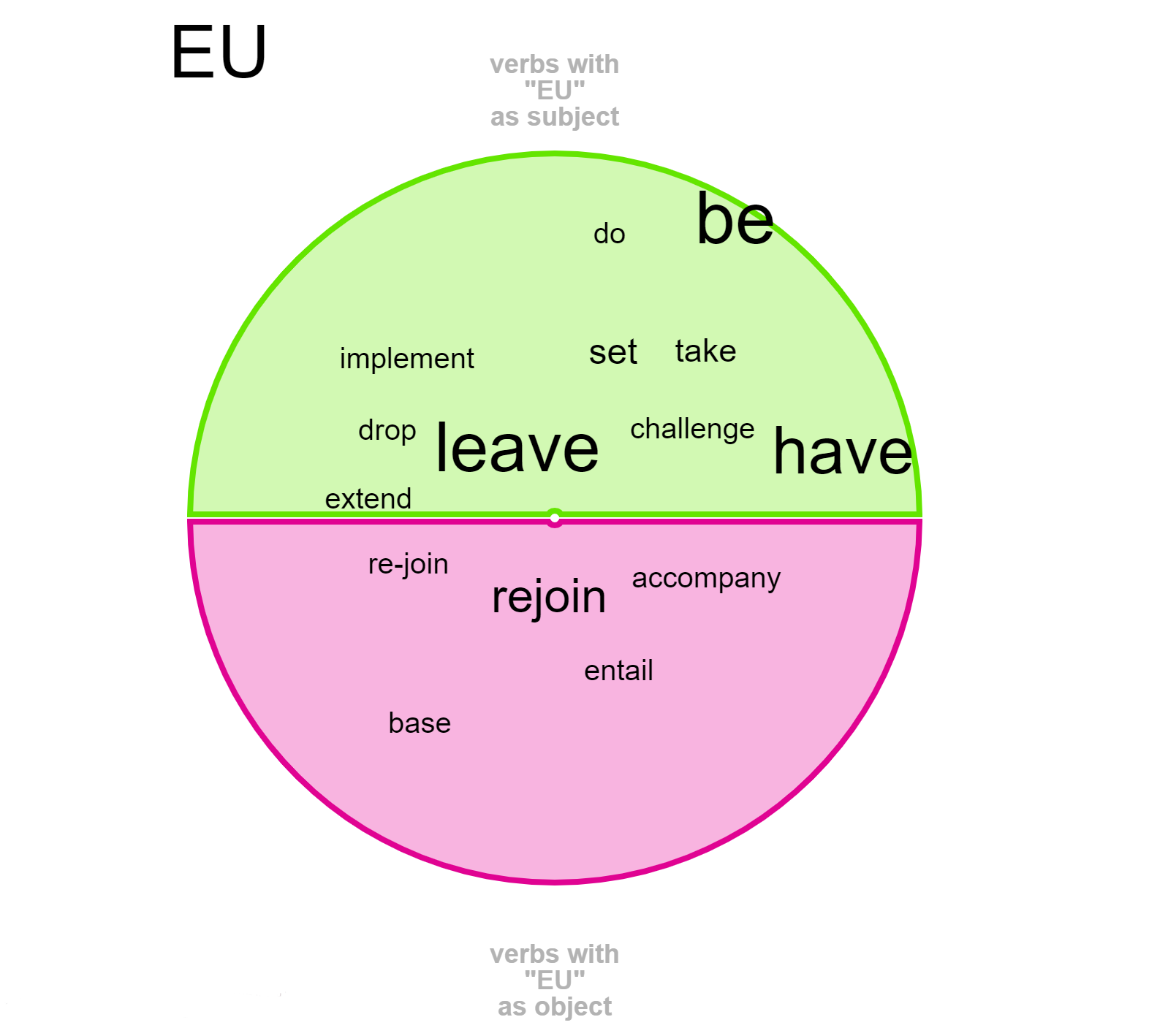

The attitudes to the theme of (FREE) TRADE AGREEMENTS are identifiable by analysing the words which co-occur with words in that theme, such as EU, which is the UK’s most significant free trade agreement. Consistent with the dictum of John Firth, ‘you shall know a word by the company it keeps’, an analysis of the words that co-occur with EU can provide an insight into respondents’ conceptualisation of the EU and, in this context, and its relevance to recommendations for the direction of Labour’s trade policy. Figure 32 presents actions associated with the EU (top of Figure 2) and actions done towards the EU (bottom of Figure 2). This is achieved through extracting verbs that co-occur with the term EU functioning as a subject (e.g. ‘The value of food exports to the EU reportedly dropped by £2.4bn in the first 15 months after Brexit) and an object (e.g. Rejoining the EU is the only way to drag ourselves out of this mess).

When interpreting visualisations such as in Figure 2, the different colours correspond to the different grammatical relations with the target word, the size of the text represents the raw frequency of the times the word co-occurs with the target word, and the closer the position to the centre of the circle, the stronger the association between that word and the target word.[8] Some words, such as have and be in Figure 2, are very frequent and thus occur within the context of EU often, but as they occur with EU little more than they occur with any given noun, the strength of association is low, hence they appear towards the perimeter of Figure 2.

Close reading of data from Figure 2 data reveals conceptualisation of the EU held by LPF respondents. Contexts of the word drop refer to the value of exports to the EU decreasing, and the uses of implement refer to recommendations for the Labour party to adopt existing EU legislation. Some uses of rejoin/re-join advocate for rejoining the EU, while others stop short of full membership but do argue for closer alignment.

Figure 2: Verbs used with the term EU.

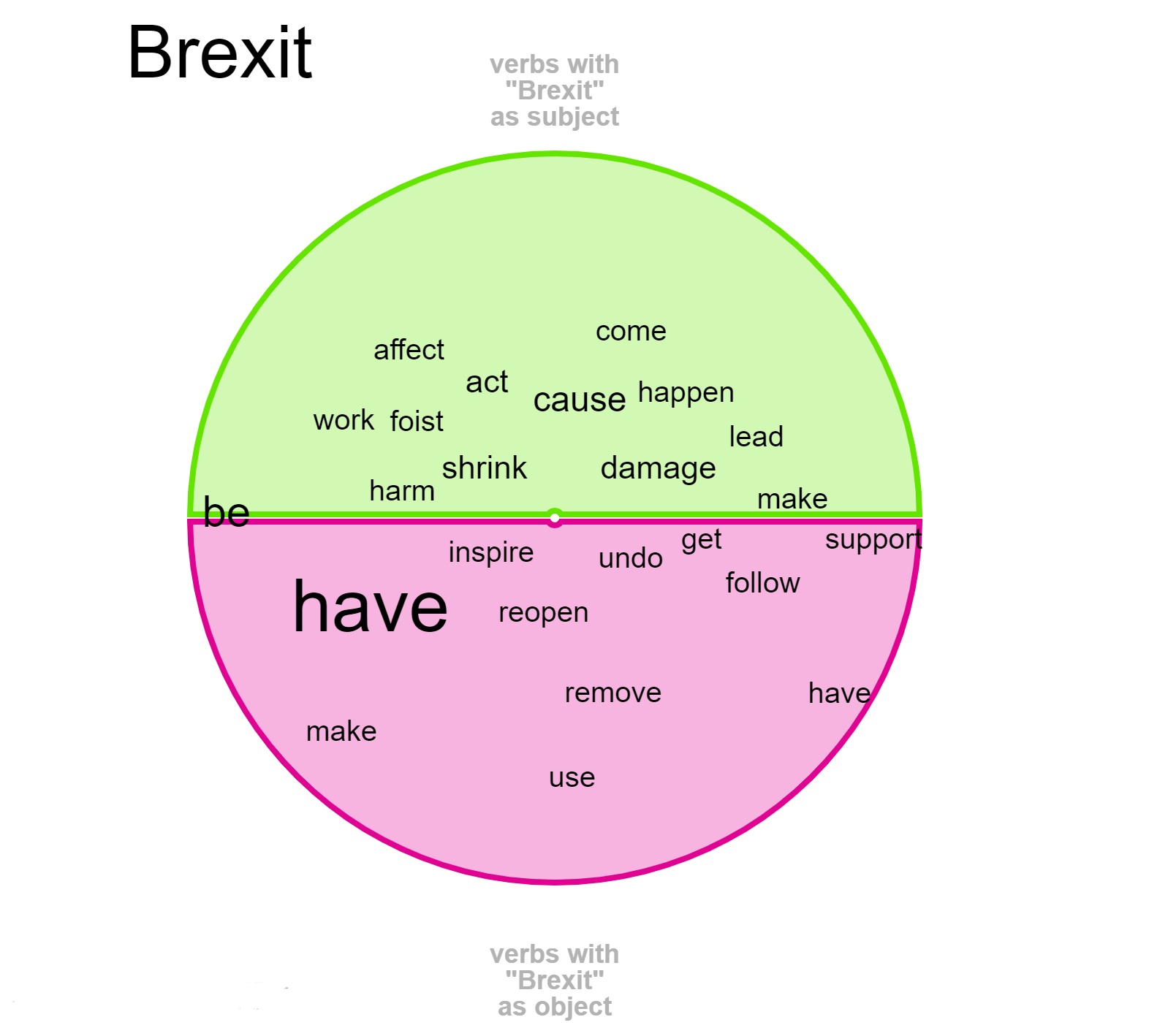

Clearer attitudes towards Britain’s exit from the EU are evident through verbs used alongside Brexit (see Figure 3). LPF respondents conceptualise Brexit as damaging, harming, and shrinking. These examples highlight a belief that the economic effects of Brexit are adverse. A desire to align more closely with the EU is also clear through verbs to undo, to reopen, and to remove. While the use of the verb to support may seem to suggest a positive framing of Brexit, close reading of the examples such as ‘young people did not support Brexit’ adds to the general negative sentiment regarding Brexit. Within the LPF responses, Brexit is also described as a bonfire and a barrier.

Figure 3: Verbs used with the term Brexit.

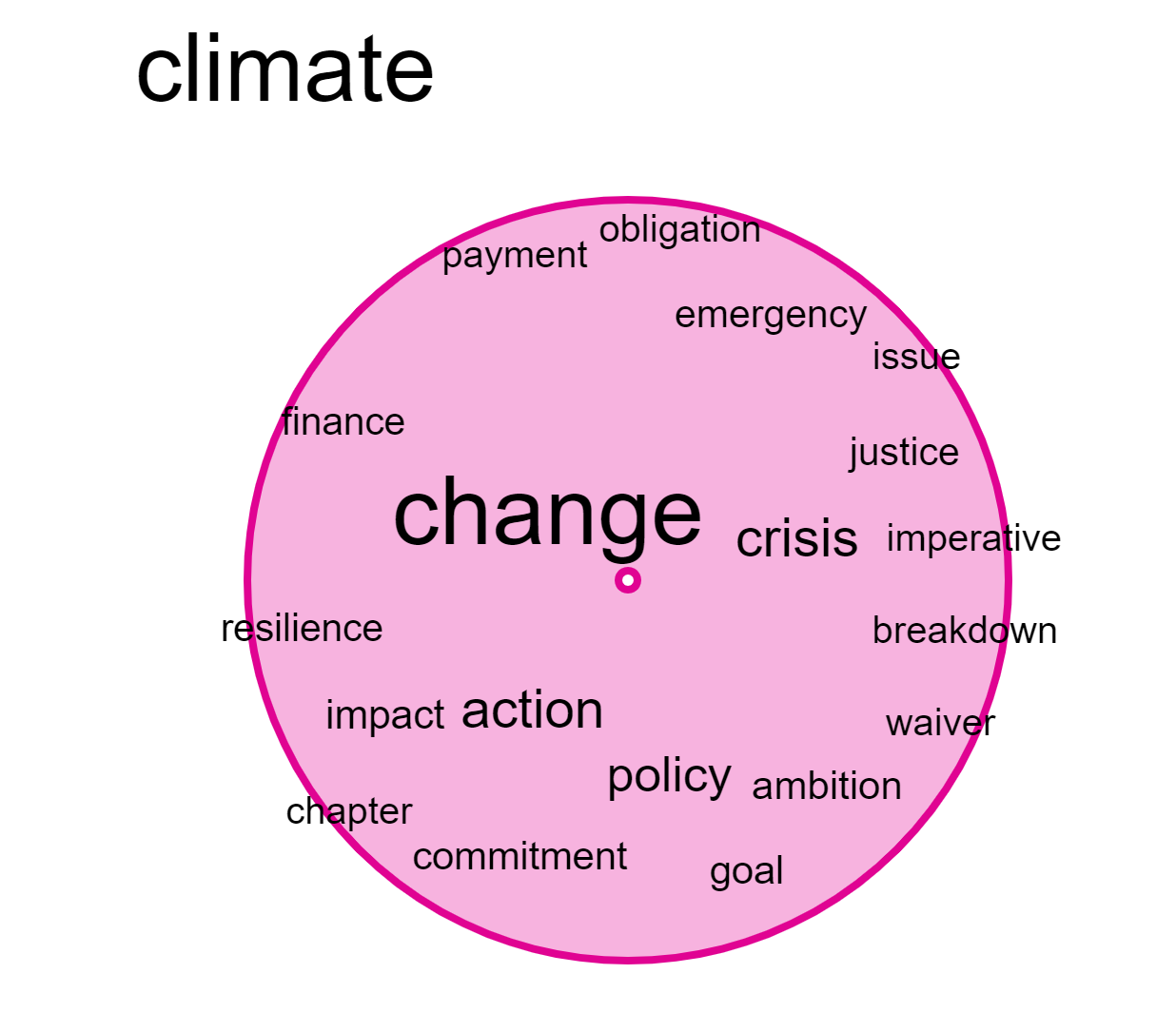

While environmental protection and net zero are foregrounded in the wording of Question 5 to the LPF, the theme of the ENVIRONMENT is discussed well beyond the specific answers to this question (for example, see the analysis of Questions 1, 2 and 3 and see Figures 5-7). The key message regarding the ENVIRONMENT is the desire for trade deals to facilitate sustainability by minimising climate change. In particular, the term climate is used 406 times in the data across 81 documents (see Table 1). Respondents’ sentiment towards climate emerges from the of the typical nouns which are modified by the term climate, see Figure 4. Climate change is considered an urgent and pressing issue. This is evident through the co-occurrences with crisis, emergency, disaster, breakdown, and imperative. Ambition, obligation, commitment, goal, and objective also speak to the ways in which trade deals are considered a mechanism through which to initiate climate action.

Figure 4: Nouns modified by the term climate.

In this section we present findings the specific responses to the seven questions posed by the 2023 Labour Policy Forum on progressive trade policy. Note that only relatively small percentages of the 302 submissions responded in such a way that made clear distinctions between the questions. For example, some did not address some or all of the questions in any way. Others collated their general thoughts relating to some or all the questions into a singular narrative.

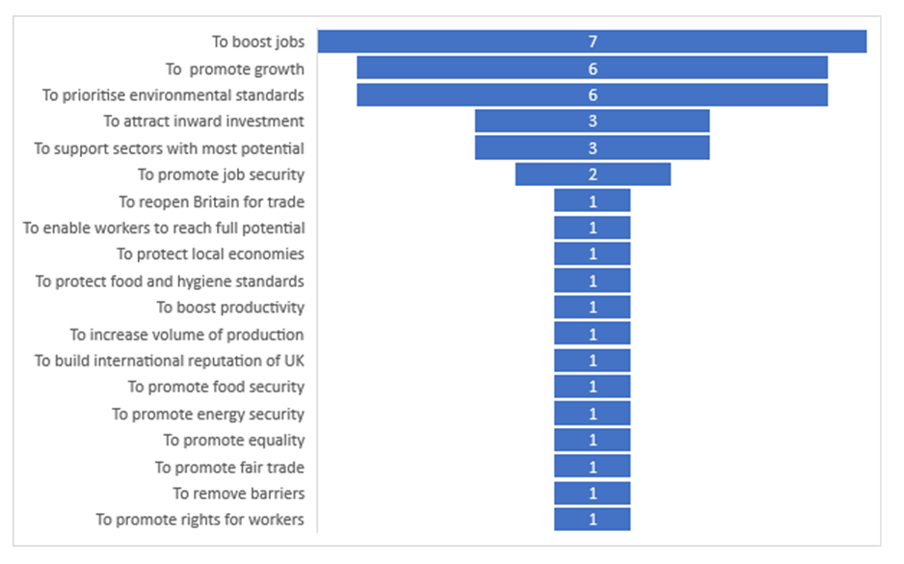

26 submissions directly answered the question. The responses to this question are categorised into the response types shown in Figure 5. Note that some submissions contained multiple suggestions. Figure 5 shows that as well as the role of trade deals in the context of boosting jobs and promoting growth, the importance of environmental standards is regularly mentioned, as well as a range of other qualifications, such as job security, food standard, economic security, that appear in fewer responses. This suggests that while jobs and growth seem important, respondents would like other factors to be considered.

Figure 5: The suggestions provided in relation to Question 1.

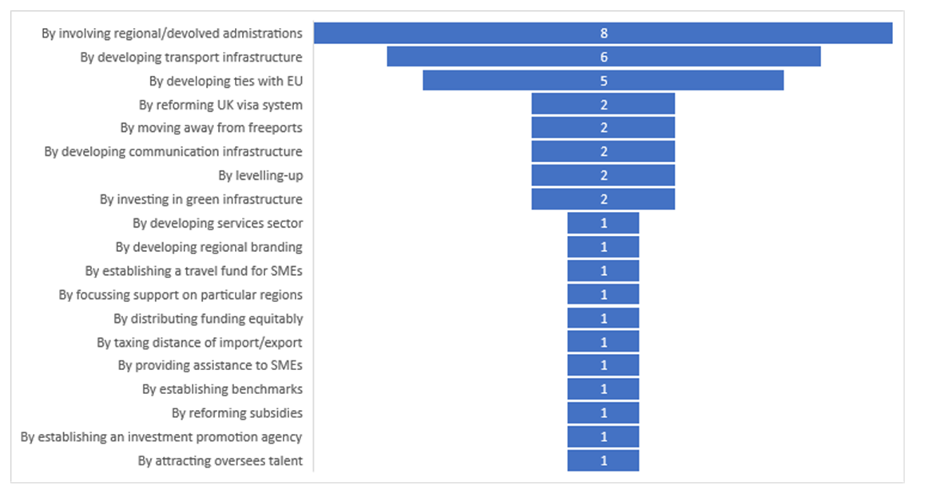

30 documents responded directly to this question. An overview of the responses can be seen in Figure 6. The clear message emerging from this is that regional and devolved government should be involved in the making of trade policy to a greater extent, that transport infrastructure should be strengthened, and that ties with the EU should be developed. There is also a range of specific suggestions including the role of communications or green infrastructure, investment assistance or regional support for SMEs.

Figure 6: The suggestions provided in response to Question 2.

The key themes in these responses (29 in total) are expressed in Figure 7. Specifically, the most common suggestions are to ensure the security of essential supply chains by more closely aligning with the EU, through protecting the environment, and by increasing domestic production.

Figure 7: The suggestions provided in response to Question 3.

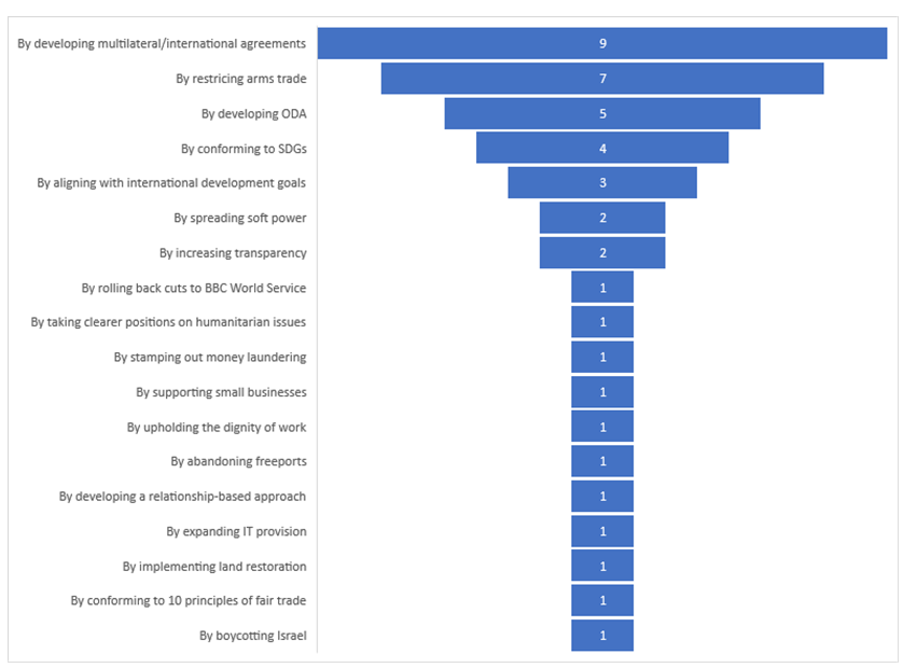

Figure 8 provides an overview of the 30 responses. The most common suggestions are that the promotion of the four areas mentioned in the question can be best addressed by engaging with multilateral/international organisations, restricting the UK’s involvement in the arms trade, and developing Overseas Development Aid.

Figure 8: The suggestions provided in response to Question 4.

Beyond the specific answers to Question 4, one of the ways in which the relative salience of the four topics mentioned in the question can be determined is by identifying the frequency of documents containing these terms (when the use of these words in the questions has been removed from the data, see Table 3).

Table 3: The frequency of documents containing the four topics in Question 4

|

Term |

DOCF |

|

human rights |

92 |

|

workers’ rights[9] |

40 |

|

fair trade |

19 |

|

global peace and security |

10 |

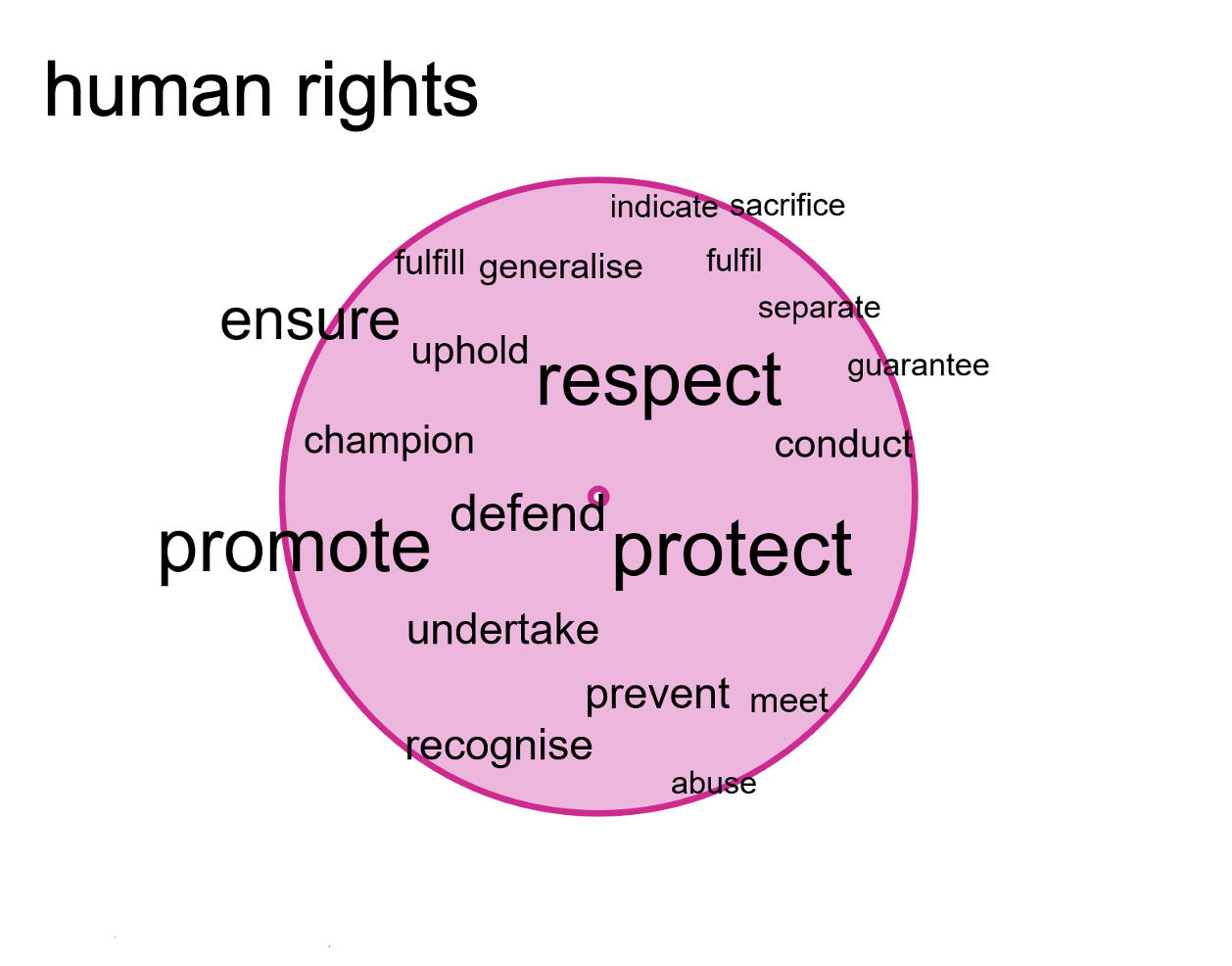

Table 3 shows that human rights is the most pressing of the four issues mentioned in Question 4. We identify the role that human rights play for LPF respondents, through the verbs that are used before the phrase (see Figure 9). The importance of human rights broadly speaks to the need for trade deals to promote them. This is highlighted through the co-occurrence of human rights with the verbs to respect, to defend, to prioritise, to address, to promote, to champion, to enhance, and to protect. Another role of trade deals lies in managing human rights, such as to mandate, to ensure, to monitor, and to assess.

Figure 9: Verbs used with the term human rights.

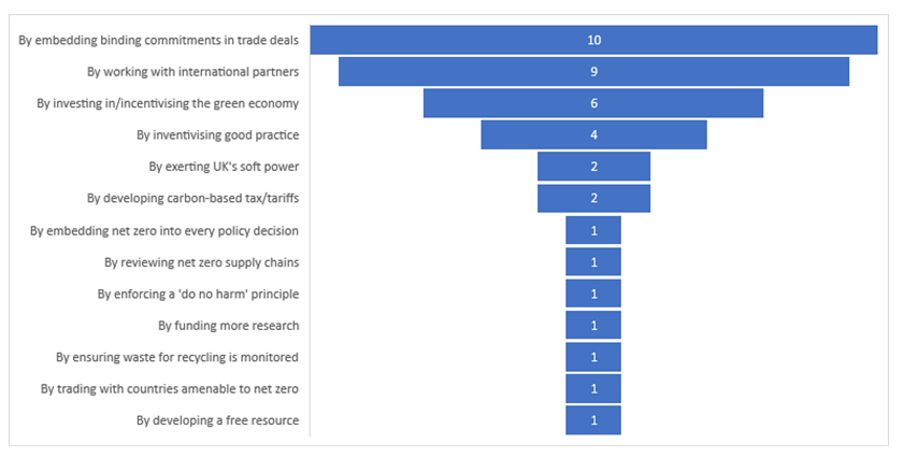

An overview of the 27 responses can be found in Figure 10. LPF respondents suggest that binding commitments to the environment should be embedded in trade deals, that international cooperation is imperative, and that the green economy should be further incentivised.

Figure 10: The suggestions provided in response to Question 5.

This question was directly engaged with by the fewest (7) respondents. Within these responses, three suggested that commitments to inclusivity be enshrined in trade agreements. Only one response provided a clear suggestion for how to better support groups protected by the 2010 Equality Act. They suggest cultivating an environment that supports business founders from groups with protected characteristics.

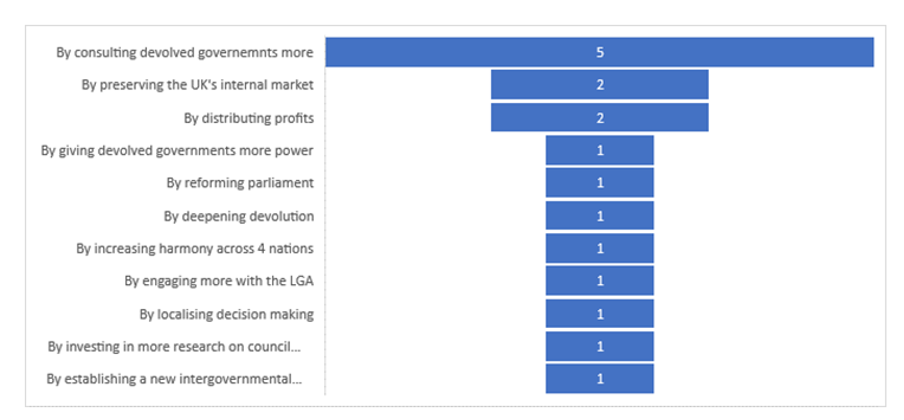

This question was directly answered by 17 submissions. An overview of the response to Question 7 is presented in Figure 11. As a result of the low response rate for this question, there are fewer clear themes. Most notably, it is suggested that devolved governments should be consulted more.

Figure 11: The suggestions provided in response to Question 7.

The Labour Party’s 2023 National Policy Forum on progressive trade generated a range of recommendations for the direction of Labour’s trade policy. There are views on broad policy stances, such as aligning more closely with the EU; overlapping with procedural and administrative recommendations, such as working more closely with the devolved administrations, as well as with international partners and multilateral fora. There are also economic considerations put forward, centring around economic growth, and job boosting and reducing poverty and inequality. In addition to these broader objectives there are also a variety of ‘trade and…’ recommendations that speak to the ways in which trade deals can be a mechanism by which further goals can be met. For example, these relate to the role of trade with regard to the climate, environmental and food standards, supply chain resilience and economic security, job security and workers’ rights, and human rights, as well as support for international development. It is worth noting that in these responses there is little sense of the trade-offs that may by involved across the policy choices. For example, raising food standards is likely to increase costs and prices, which may impact on poverty and inequality.

Given these responses it is interesting to see the extent to which they are reflected in the Labour Party election manifesto recently released (13th June 2024). From the manifesto we see that international trade is explicitly mentioned 16 times in the document. Analogously to the analysis in Tables 1 and 2, the frequency with which trade appears is four times higher than would be expected in normal usage, i.e.in comparison to the baseline data set. Similarly,[10] the use of free trade agreements and the EU appears in the manifesto with a higher relative frequency than the baseline. The explicit discussion of trade is to be welcomed, but overall, the space devoted to trade is not very extensive.

It is clear from the manifesto that some of the key issues identified in the consultation documents do form part of the proposed policy agenda should the Labour Party be successful in the general election. We can see this regarding the commitments to greater representation and involvement of the devolved administrations in trade negotiations, in the desire for closer relations with the EU, and in the recognition of the overall importance of trade for UK economic growth, and regarding maintaining food standards. However, we note that there is no explicit discussion or linkage of trade and trade policy to the range of additional ‘trade and…’ recommendations that were in the consultation process – be this, for example, regarding environmental standards, human rights or economic security. This is not to say that concerns about the environment, rights, security are absent from the rest of manifesto. Indeed, the reverse is the case. It is the link with trade and trade policy which is absent.

We do see in the manifesto an explicit commitment to a statutory ‘Industrial Strategy Council’ and to the publication of a trade strategy, which is to be aligned with the industrial strategy. This is also to be welcomed because such initiatives are (hopefully) more likely to lead to greater transparency and stability in domestic policy and trade policy and thus more likely to result in productive investment and economic growth. Of course, whether or not policies consistent with the preceding are introduced will ultimately depend on the outcome of the election, and the subsequent decisions taken – by whoever is the next government.

Overall, our assessment[11] is that the recently released Labour Party manifesto is consistent with the 2023 Labour National Policy Forum consultation in some of the direct trade related commitments made, and potentially implicitly consistent regarding some of the ‘trade and…’ issues. However, the extent of this will depend on the promised trade strategy should the Labour Party be elected.

All this suggests that perhaps, consultative process can be genuinely useful and inform policy making.

[1] https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Labour-Party-manifesto-2024.pdf ; and https://public.conservatives.com/static/documents/GE2024/Conservative-Manifesto-GE2024.pdf

[2] https://policyforum.labour.org.uk/commissions

[3] Typicality score measured by LogDice, indicates the strength of the collocation. The higher the score, the stronger the collocation.

[4] Collocation is a pair of terms which co-occur more often than would be expected by chance.

[5] We use the Ententen21 corpus, which is a collection of more than 52 billion words scraped from the web between October 2021-January 2022. The corpus is available via SketchEngine.

[6] See Savický & Hlavácová (2002).

[7] We also remove self-evident words and phrases, such as UK, trade, and Labour Party which, given the nature of the LPF, do not provide insight into respondents’ beliefs or wishes regarding trade policy.

[8] The left/right and up/down dimensions (within each grammatical category) are not meaningful.

[9] This includes 31 responses with an apostrophe and nine without the apostrophe.

[10] Interestingly the relative frequency of all of these three terms is higher in the Conservative Party 2024 manifesto, than that of the Labour party. However, any detailed discussion of this finding is beyond the scope of this Briefing Paper.

[11] References used in this Briefing Paper include: Kilgarriff, Adam., Vít Baisa, Jan Bušta, Miloš Jakubíček, Vojtěch Kovář, Jan Michelfeit, Pavel Rychlý, Vít Suchomel. (2014). The Sketch Engine: Ten years on. Lexicography, 1 (1), 7-36.

Labour Party Manifesto. (2024). Available via https://labour.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/Labour-Party-manifesto-2024.pdf. Accessed 13th June 2024.

Conservative Party Manifesto. (2024). Available via https://public.conservatives.com/static/documents/GE2024/Conservative-Manifesto-GE2024.pdf. Accessed 13th June 2024.

McEnery, Tony. & Andrew Hardie. (2011). Corpus Linguistics: Method, Theory and Practice. Cambridge University Press.

Neame, Katie (2023) “Revealed: Full final policy platform set to shape next Labour manifesto”. Labourlist. Published 5th October 2023. Available via https://labourlist.org/2023/10/labour-national-policy-forum-final-document-summary-policy-manifesto-party-conference/#six

Savický, Petr. & Jaroslava Hlavácová. (2002). Measures of word commonness. Journal of Quantitative Linguistics, 9 (3), 215-231.

SketchEngine. Available via http://www.sketchengine.eu/

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher June 14th, 2024

Posted In:

30 May 2024 – I

30 May 2024 – I

ngo Borchert is Deputy Director of the UKTPO, a Member of the Leadership Group of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex. Michael Gasiorek is Co-Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex. Emily Lydgate is Co-Director of the UKTPO and Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Sussex. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the CITP and former Director of the UKTPO.

ngo Borchert is Deputy Director of the UKTPO, a Member of the Leadership Group of the Centre for Inclusive Trade Policy (CITP) and a Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex. Michael Gasiorek is Co-Director of the UKTPO, Co-Director of the CITP and Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex. Emily Lydgate is Co-Director of the UKTPO and Professor of Environmental Law at the University of Sussex. L. Alan Winters is Co-Director of the CITP and former Director of the UKTPO.

A general election is underway, and the parties are making various promises and commitments to attract voters, and both the main parties – the Conservatives and Labour – are keen to persuade the country that they have a credible plan. Now it might just be that the authors of this piece are trade nerds, but one key aspect of economic policy has not yet been clearly articulated, or even mentioned – and that is international trade policy.

In our view, this is a mistake. As a hugely successful open economy, international trade constitutes a significant share of economic activity, supports over 6 million jobs in the UK, spurs innovation, and enhances consumption choices. In short, trade and investment flows are an important element in leading to higher economic growth and welfare. In addition, trade and investment relations intertwine considerably with increasingly fraught geopolitics. Against this backdrop, the UK cannot afford to give trade policy short shrift.

Admittedly, though, trade policy is complex. It is also, more than ever, linked to other dimensions of public policy – and that does make it harder to have simple soundbites. That is no doubt part of the explanation why trade hasn’t been mentioned. The other part is that discussions of trade policy are closely intertwined with the ‘B’ (Brexit) word, and those discussions have become somewhat toxic.

Nevertheless, we argue that sound trade policy is a high priority for the UK. Listed below are some practical, feasible, and specific policy proposals that would help to ensure a better and more coherent UK trade policy, and thus lead to more equity in trade outcomes as well as higher rates of economic growth for the UK.

Process and consultation

1. Publish a Trade Strategy, which should elucidate principles as well as concrete policy objectives and intentions. Recognise the importance of both goods and services trade policy for the UK economy, nationally and across the regions.

2. Reduce executive power over trade policy, through establishing an independent Board of Trade, strengthening Parliamentary oversight over Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and improving consultative processes with devolved nations and with stakeholders in trade.

3. Ensure and commit to transparency in UK trade data, good access to data for researchers and be transparent about the analyses undertaken by government.

Policy Areas:

4. Plurilateral / Multilateral / World Trade Organization (WTO):

a. Ensure that UK trade policy remains consistent across its various partner countries and across the different free trade agreements notably with regard to regulatory approaches.

b. Ensure that trade policy supports the rules of the multilateral trading system. Work on policy areas, such as supply chain security, bilaterally and multilaterally in ways which are at a minimum consistent with this, if not designed to strengthen multilateral cooperation.

c. In the absence of an effective WTO dispute settlement mechanism, join the Multi-party Interim Appeal Arbitration Arrangement (MPIA).

5. Bilateral trade relations:

a. Do not expect too much from further, notionally comprehensive, free trade agreements with more countries. Focus more on improving the workings and utilisation of existing agreements.

b. Work to reduce costs of trade with the EU in both goods and services, e.g. by mutual recognition agreements on standards, qualifications and certification and negotiating an EU-wide youth mobility scheme. As a first step seek a veterinary agreement.

c. Seek to cooperate with the EU on environmental regulation that impacts upon trade, most immediately by linking ETS schemes with the EU and introducing a compatible CBAM.

d. Review rules of origin with the EU and seek improvements where there may be benefits to both parties (eg. Electric vehicles and car batteries).

6. Domestic:

a. Provide better resourcing and introduce more robust border checks to uphold the UK’s high food standards and prevent the introduction of pest and animal diseases.

b. Work closely with industry to make sure that the implementation of new border arrangements, including the Border Target Operating Model and the Windsor Framework/UK internal market, are understood by businesses and don’t create perverse incentives to UK internal trade, imports or exports. SMEs are likely to face particular challenges.

c. Have a clear digital strategy which deals both with the digitisation of trade transactions and processes, and the rise in digital trade. This strategy should set out the balance of objectives with regard to consumer protection, cyber security, and competitiveness.

This is by no means intended as a comprehensive list, but focusses on some key principles, and specific priorities which are feasible, would make a difference, and could be immediately focussed on. When the manifestos are published it will give an opportunity to assess the parties’ approaches to trade policy and to see whether proposals go beyond broad statements of intent by providing practical details and commitments in line with any of the above.

Disclaimer:

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author alone and do not necessarily represent the opinions of the University of Sussex or the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Republishing guidelines:

The UK Trade Policy Observatory believes in the free flow of information and encourages readers to cite our materials, providing due acknowledgement. For online use, this should be a link to the original resource on our website. We do not publish under a Creative Commons license. This means you CANNOT republish our articles online or in print for free.

Jessie Madrigal-Fletcher May 30th, 2024

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, General Election 2024, trade policy, UK Election

Subsidies granted by third states

The Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR)

The definition of a concentration

Ex ante mandatory notification: qualifying thresholds

An actual or potential distortive effect on the EU internal market

The definition of economic coercion

Compatibility with international law

Cosmo Rana-Iozzi October 12th, 2022

Posted In:

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

23 May 2022

23 May 2022

Peter Holmes is a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory and Emeritus Reader in Economics at the University of Sussex Business School

UK trade with Europe has significantly fallen off (see UKTPO BP 63 for an early assessment). UK GDP has fallen by 4%. If we cancel the Northern Ireland Protocol (NIP) – which is all the talk at the moment – the economic consequences of Brexit will get worse and let’s not even think about the political consequences. Is any of this fixable? Yes, if we look ahead to 2025 when the Brexit agreement with the EU—formally known as the EU-UK Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) —is up for its 5-yearly review. UK stakeholders, including political parties planning their manifestoes ahead of the next UK general election in 2024, should consider their Brexit positions now – but it’s not a case of leave or remain, rather a case of ‘tweak the Brexit agreement to something that better suits us’. (more…)

Cosmo Rana-Iozzi May 23rd, 2022

Posted In: UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, Frictionless trade, Irish border, Northern Ireland Protocol, TCA, Trade and Cooperation Agreement

Competition Provisions in International Trade Agreements

New Directions for the Use of State Aid in the UK

What Kind of State Aid Scheme Will the UK Implement?

A State Aid Plan for Domestic Policy

George Meredith June 19th, 2020

Posted In:

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

8 June 2020

8 June 2020

Professor Erika Szyszczak is Professor Emerita and a Fellow of UKTPO, University of Sussex.

Control over state aid is a stumbling block for the future of a EU-UK trade agreement. The EU is seeking dynamic alignment of any future UK state aid rules. This is a bold demand, especially since the EU state aid rules will be in a state of flux in the forthcoming years. But if no agreement is reached there are implications for domestic UK policy. (more…)

George Meredith June 9th, 2020

Posted In: UK- EU

Tags: State aid

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

12 December 2019

12 December 2019

Michael Gasiorek is Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex and a Fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory. Nicolo Tamberi is a Research Assistant in Economics for the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

Following Brexit, and assuming the UK is no longer part of a customs union with the EU, the UK will be able to sign free trade agreements (FTAs) with third countries. Indeed, the Conservative manifesto aims to have 80% of UK trade covered by FTAs within three years. This is clearly unrealistic, because it would require signing agreements with more than 12 countries within a time-scale which has rarely been achieved for a single agreement. The objective, however, highlights that, post-Brexit, there will be a lot of focus on trying to sign FTAs. Other than the somewhat significant matter of signing an agreement with the EU, top of the UK’s FTA wish list is an agreement with the US. (more…)

Charlotte Humma December 12th, 2019

Posted In: Uncategorised

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() 11 December 2019

11 December 2019

In the lead up to the General Election, we have analysed the manifestos of the five main political parties and what they imply for future UK trade.

Overall, we find that the manifestos in this General Election are incoherent and vague on trade and contain several unachievable targets. (more…)

George Meredith December 11th, 2019

Posted In: UK - Non EU, UK- EU

Tags: Election, Manifesto, trade policy

Share this article: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

4 December 2019

4 December 2019

L. Alan Winters CB is Professor of Economics and Director of the Observatory.

The Prime Minister seems to think that an ‘oven-ready’ Brexit deal is the best that we can choose from the menu of policy alternatives. It sounds neither appetising nor nourishing, but if it really were quick and easy, maybe it would be worth it.

But it’s not quick or easy: ‘oven-ready’ is just not true. (more…)

Charlotte Humma December 4th, 2019

Posted In: UK- EU

Tags: Brexit, oven-ready, Regulations, tariffs, withdrawal agreement

The nature of inward FDI to the UK

What are the most common source countries of investment in the UK?

Why do different firms want to invest here?

How strong is the UK’s performance in attracting FDI compared to other European countries?

The impact of the Brexit vote on inward foreign investment to the UK

Political uncertainty: timeline of Brexit

FDI in the lead-up to and after Brexit: performance of the ‘real’ and ‘synthetic’ UK

FDI cost of Brexit to date across sectors: manufacturing and services

Has the Brexit vote disrupted investment by supply chain multinational firms?

The UK continues to perform strongly in attracting inward foreign investment, and remains one of the largest recipients of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in Europe and globally. In 2017, there were close to 1,000 greenfield investment projects announced for the UK: these created approximately 60,000 new jobs and were valued at just over US$ 33 billion.

The UK’s strength lies in the services sector: the areas with the largest number of individual FDI projects include software & IT services, business services and financial services.

However, in 2017, the UK was overtaken by Germany as the largest European recipient of FDI, with France also gaining ground. The UK share of EU28 FDI has fallen from some 25 per cent in early 2015 to some 18 per cent in late 2017.

Since the EU referendum, inflows of FDI to the UK have followed a downward trend: the longest continuous decline since the beginning of the data series in 2003.

Our analysis shows that the Brexit vote may have reduced the number of foreign investment projects to the UK by some 16-20 per cent. For services FDI, the gap is even larger: investment may be some 25 per cent lower than if the UK had voted to remain in the EU.

While investments continue to flow into the UK, there is a decline in investment in sectors such as ‘software publishing’, ‘investment management’ and ‘retail banking’. These are high-value-added industries, so the threat of Brexit has put high-skilled jobs at risk. (more…)

Charlotte Humma October 31st, 2018

Posted In: