Liam Berriman, Lecturer in Digital Humanities/Social Science

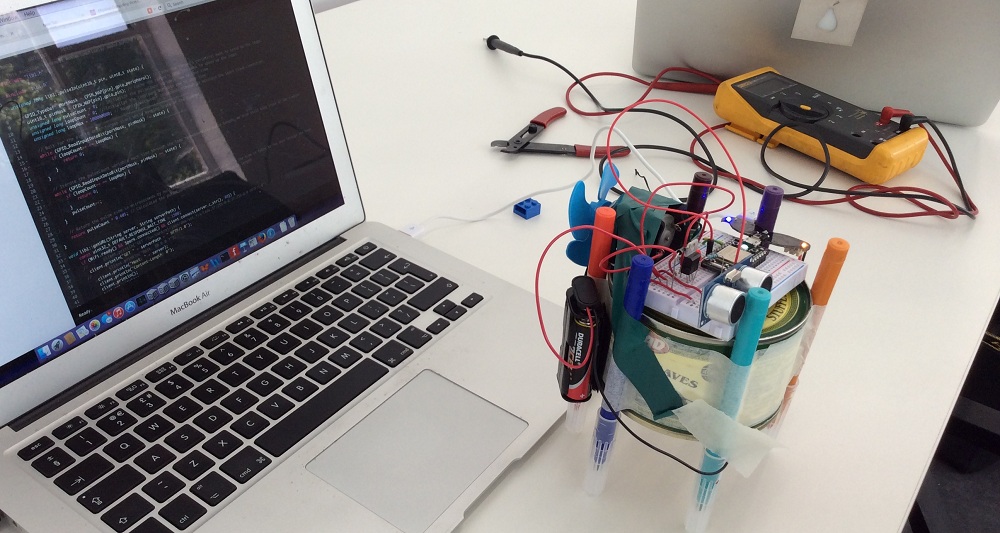

Over the last couple of months I’ve been involved in the development of a project with colleagues at the Sussex Humanities Lab that will look at how we conduct participatory research with children and young people using digital devices. As part of the project we will explore new ways of using different computational methods to ‘hack’ digital devices in order to make participation in research more accessible to different groups of young people. One aspect of this study will look at how we might experiment with the affordances of digital devices as ‘research tools’ in order to re-configure how they are used and the kinds of data they generate.

During the last decade, digital devices have become popular research tools for participatory and ethnographic research with young people. A great deal of participatory youth research now involves researchers and/or participants taking photographs or recording sounds using readily available digital devices, such as mobile phones. Whilst these digital devices have been used to produce a lot of fascinating research on young people’s lives, they often leave open a number of unanswered methodological and ethical questions around the mediatory role of digital devices in research. Here, I want to briefly reflect on three important ways that we need to re-think the role of digital devices in participatory research with young people:

1. Digital devices as ‘black boxes’ – A key challenge of digital devices in research are the way they ‘black box’ the processes of data collection, storage and circulation. Bruno Latour has described how ‘black boxing’ occurs “whenever a piece of machinery or set of commands is too complex” and we (as users) “need to know nothing but its inputs and ouputs” (2000: 681). For the most part, our understanding of how digital devices work, and what they are capable of, is mediated by simplified visual interfaces of menus and settings. Consequently much of the computational complexity of digital devices remains hidden from view, leaving large gaps in our knowledge as to precisely what data are collected (e.g. metadata such as GPS location), how that data is being stored (e.g. local memory or cloud services), and how that data is handled and circulated (e.g. via encrypted or unencrypted channels). These gaps in our knowledge pose significant issues for what role we allow digital devices to play in capturing data that may be ethically sensitive.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/SussexHumanitiesLab/

2. Digital devices as commercial products – Related to the first point, digital devices are commercially manufactured products that have not been designed for use as research tools. As researchers we ‘appropriate’ these devices, drawing on existing affordances of devices (e.g. portability, camera functionality) to facilitate specific research activities. In recent years there have been a number of innovative studies that have creatively appropriated digital devices into research – stretching and subverting their affordances. Nonetheless, the potential uses of these devices for research are by-and-large limited to the parameters set by their consumer-driven design. Consequently, the possibilities for what kinds of data can be generated are often pre-determined and closed down by their design specifications.

3. Digital devices as ‘democratising’ research? – The growing ubiquity and availability of digital devices in everyday life has paved the way for growing numbers of studies that invite participants to capture data about their lives (see for example Wendy Luttrell’s Children Framing Childhoods and Wilson & Milne’s Young People Creating Belonging). In the ‘Face 2 Face’ and ‘Curating Childhood’ studies, we invited young people to record a ‘day in their life’ using either their own digital devices or ones supplied by us. A lingering question from these studies was the extent to which such activities might be seen as ‘democratising’ research and enabling participants to share their lives on their own terms. In particular, the extent to which the parameters of research participation are foreclosed by a particular digital device. In part, this requires a more honest assessment of what forms of research participation digital devices both ‘open up’ and ‘close down’, and how this might vary for different groups of young people taking part in research (e.g. with physical disabilities).

Our study currently under development will explore new ways of ‘opening up’ digital devices within participatory youth research. In order to challenge digital devices as closed data ‘black boxes’, we will seek to explore new participatory research methodologies that involve young people ‘hacking’ research tools and specifying their affordances (such as sensory inputs) for themselves.

Liam Berriman April 23rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: digital data, digital devices, hacking, Liam Berriman, participatory research, Sussex Humanities Lab, youth research

Leave a Comment

In the second of a series of blog posts, Suzanne Rose and Anthony McCoubrey from the Mass Observation Archive reflect on their participation in the ESRC Festival of Social Science event: the ‘My Object Stories’ Hackathon and the significance of ‘object stories’ for the Archive.

This was the third year in a row that the Mass Observation Archive (MOA) has taken part in the ESRC Festival of Social Science, which takes place nationally to promote social science research to non-academic communities and the wider public. The MOA hosted two events, which were part of a programme of over 200 events taking place across the country celebrating the social sciences.

‘Mo’, the Mass Observation Archive’s teddy bear mascot, volunteers to pilot the fiducial tracker.

This year our events we focused on engaging young people with the MOA and considered how archives relate to the digital age. One event was a day long workshop for pupils from Ratton School at the MOA at The Keep and the other was the My Object Stories Hackathon. This was designed to be a public event targeting young people, which would provide an opportunity for them to develop their understanding of the MOA and experiment with digital technology.

Working in partnership with CIRCY, the Department of Social Work and UoS Humanities Lab, provided a fantastic opportunity to engage the young people with the latest technologies and to invite them to share their objects and their stories with the archive in unique and interesting ways.

The young people who took part in the Hackathon were asked to bring an object with them, which had a particular significance to them and to share their story with the team. They brought a range of objects with them, from a One Direction flag, favourite bo

oks, plastic animals and a guitar and even a pair of Dr Martens boots and all had a personal story to share. These object stories were captured through discussion with the young people, before being presented to be photographed and interviewed and recorded, before being transformed into a digital installation by colleagues much techier than myself.

I really enjoyed working with the young people to find out about their objects and explore their stories. So much of what we hold in the Mass Observation Archive is peoples’ stories and so it was really exciting to be working with  young people who were eager to share their stories with us.

young people who were eager to share their stories with us.

The objects they chose were also very interesting and of their time with particular personal significance attached and the young people spoke very thoughtfully about why they had chosen their object and what it meant to them.

Some objects such as the One Direction flag were especially timely, given the bands recent loss of member Zayn Malik and decision to take time out from performing. This marks a significant event in the lives of many Directioners and something which should be captured in the archive.

Other objects were more timeless, such as the Dr Martens boots, which marked the connection between the present day and generations of people who have loved and worn them over time. The young person spoke about how her mum had also collected DM boots in her youth and so this object also had significance for her and her family and traditions within it.

Objects are often held onto for very personal reasons and we were very privileged that the young people felt able to share their stories with us and that these stories and their significance will be captured for the archive collection.

Within the next few months we look forward to presenting the a roundup of the Hackathon’s events in an installation and inviting the young people back to see their amazing contribution as well as depositing some of the photographs and recordings in the Everyday Childhood Collection at archive collections at The Keep.

Liam Berriman January 12th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: Anthony McCoubrey, archive, everyday, Favourite things, hackathon, Mass Observation, object stories, Sussex Humanities Lab, Suzanne Rose

Leave a Comment

In the first of a series of blogs, researchers Rachel Thomson and Liam Berriman reflect on how hackathons might be used as a participatory methodology that span the digital humanities, social science, design and computing.

Talk to me.

Rachel Thomson

On Saturday 14th November I had the pleasure of taking part in an event billed as a ‘Hackathon’ hosted by the Sussex Humanities Lab, CIRCY and the Mass Observation Archive. Hackathons are ‘events in which computer programmers and others involved in software development and hardware development, including graphic designers, interface designers and project managers, collaborate intensively on software projects’.

The day was called ‘my object stories’ and the shared project was to explore ways in which we could bring to life young people’s stories about favourite everyday objects – building on work that we have been doing as part of the Curating Childhoods project which is creating a new multi-media collection within Mass Observation called ’Everyday Childhoods’. The shared task was to invent strategies through which everyday objects – cherished by young people – might talk to an audience and enrich the archive. This might be a pair of Dr Martens boots, a book, a guitar, plastic animals….

Often projects are done in separate stages, with people responsible for their ‘bit’. The hackathon model brought together all the different actors involved in the lifecycle of a research and development project to see what we could get done in a day. In this way, the event created a live interface between processes of data collection, archiving and animation.

The day started and ended with the archive. Young people brought in cherished objects to share as windows into their everyday lives. Researchers and archive outreach officers worked with them to brainstorm what they might want to say about their objects. Photographer Crispin Hughes then collaborated with them to design still images that captured their object, and film maker Susi Arnott recorded them talking about their object’s value and personal meaning.

The digital data was then sent downstairs into the lab where they were used as raw materials for three different data animation strategies. Ben Jackson and Cathy Grundy brought images and sound together within a augmented reality environment – creating short animated films. Manuel Cruz used Unity game design software to make simple games through which a player could encounter objects and stories as part of game pl ay. Chris Kiefer and Thanos Liontiris used motion tracking technology (cameras trained on a fiducial) hooked up to two different platforms: supercollider, through which sound could be triggered by movement, and a second platform which managed visual data projected onto a table acting as a screen. This meant that the object could be moved through a space – with the movements used to reveal images and sound. Young people came down and worked on shaping the three different versions of their object stories.

ay. Chris Kiefer and Thanos Liontiris used motion tracking technology (cameras trained on a fiducial) hooked up to two different platforms: supercollider, through which sound could be triggered by movement, and a second platform which managed visual data projected onto a table acting as a screen. This meant that the object could be moved through a space – with the movements used to reveal images and sound. Young people came down and worked on shaping the three different versions of their object stories.

What I liked most about the day was the way in which all the different ‘experts’ involved got to check out what each other do. I was probably very annoying, looking over shoulders, interrupting and asking questions and no doubt slowed things down. In a day we managed to get a lot done, though nothing ‘finished’. However we did manage to imagine three different ways in which the ‘show and tell’ of research might be achieved in collaboration with digital design. Each of the strategies could provide an interface through which archived data could be accessed and mediated.

The archivists had a think about how the audio and visual data might be cataloged in the archive and spoke with the developers and the researchers about how their different approaches to organising the material might relate. We also gained insight into the kind of work that might be involved in each of the strategies for animation, providing insights for costing future projects.

The day formed part of an ESRC festival of social science, showcasing to the public the relevance and potential of social research. Our aim was to open up the process through which researchers may co-produce ‘data’ with young participants and to explore the way in which this might be re-used and brought to life in different ways. Building on our earlier work with Mass Observation we wanted to show that an archive need not be seen as a dusty and distant place, but rather the starting point for a range of creative engagements. What is brilliant about the Mass Observation Archive is that it celebrates the mundane and the everyday, believing that in ten, fifty, one-hundred years time people will be as fascinated by hearing about a pair of Dr Marten boots – as we are now excited to know about what people had in their wardrobes in 1945. But the hackathon helped us glimpse how we might use this material right here and now as a starting point in creative experiments with ‘data’.

Hackathons as participatory methodology?

Liam Berriman

Hackathons have become an increasingly commonplace methodology for exploring and experimenting with data. Recent examples of this trend have included calls from archives for programmers and software developers to come and ‘hack’ their collections, and the growth of competitions where young people are invited to play with open-access datasets. Bridging these events is a growing sense of hackathons as a space for playing with archives and data.

The ‘My Object Stories’ workshop was my first experience of organising (and taking part in!) a hackathon. Over the past year, I’ve become interested in hackathons as a methodology for engaging young people with their own research data – providing a creative space for playing with the re-animation (or ‘hacking’) of data (McGeeney, 2014). Hackathons are often billed as collaborative events that draw on the participation and collective skills of all involved, and i’ve been curious about how hackathons might be used to engage young people in research beyond the data collection process.

The ‘My Object Stories’ workshop was my first experience of organising (and taking part in!) a hackathon. Over the past year, I’ve become interested in hackathons as a methodology for engaging young people with their own research data – providing a creative space for playing with the re-animation (or ‘hacking’) of data (McGeeney, 2014). Hackathons are often billed as collaborative events that draw on the participation and collective skills of all involved, and i’ve been curious about how hackathons might be used to engage young people in research beyond the data collection process.

Though excited by the creative possibilities that hackathons open up, I’ve remained cautious about overstating their potential as ‘participatory’ methods. In past research I’ve voiced scepticism about co-design practices with young people that claim to be participatory. My main concern being that researchers and designers have become very good at speaking the discourse of participation, but are often uncritical about participation’s potential ‘unevenness’ in practice (Berriman, 2014). As such, I approached this event as an experiment in data collection and re-animation, but also as an event in need of critical reflection.

In many ways our hackathon was atypical in format, with the young people creating the data to be ‘hacked’. This created an intensely personal connection between the young people and the hackathon data, with each participant principally concerned with hacking their own data. One of the main challenges this raised was in terms of equipping each young person with the skills and resources to ‘make something’ of their data. Our adult hacker team were on hand to help guide participants through possible data re-animation techniques of varying complexity (ranging from free app tools to game design engines.) The hackathon’s collective expertise and interests therefore played a significant role in defining the potential scope of data animation activities.

The hackathon is therefore a highly situated event that is contingent upon the collaborative pooling of expertise around a common project. Participation is characterised less by unbridled creativity, and more by a curiosity to explore what was possible in a space of assorted interests and expertise. In this respect, the hackathon provides us with a method for engineering collaborative spaces where people with different skills and expertise can come together to experiment with new ways of playing with data.

To find out more about the My Object Stories Hackathon, contact Liam Berriman (l.j.berriman@sussex.ac.uk)

The My Object Stories Hackathon was co-hosted by the Sussex Humanities Lab, the Mass Observation Archive, and the Centre for Innovation and Research in Childhood and Youth. It was funded with support from the ESRC Festival of Social Science and the EPSRC Cultures and Communities Network +.

Liam Berriman December 11th, 2015

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: archive, everyday, Favourite things, hackathon, Liam Berriman, Mass Observation, object stories, Rachel Thomson, Sussex Humanities Lab

One Comment