We’re delighted to announce that our book is now published and available to read immediately!

The book has been published by Bloomsbury under a Gold Open Access agreement, and you can read it for free either online or in PDF format via this link: http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350011779

Alternatively, if you would like a physical copy of the book, the paperback version is available from most online bookshops.

On Monday 29th May we will be holding a book launch/seminar to celebrate the book’s publication. The event will be held at the University of Sussex’s ‘Digital Humanities Lab’ (Silverstone Building) from 4-7pm, and is jointly hosted by the Centre for Innovation and Research in Childhood and Youth (CIRCY) and the Sussex Humanities Lab (SHL). If you are nearby, please do come and celebrate with us with a glass of wine.

Finally, we’d like to thank all of our wonderful collaborators, colleagues and families for their support in helping us to get this book out. We would especially like to thank all of the participants and families involved in our study whose willingness to allow us into their everyday lives made this book (and the projects behind it) possible.

We’ve been very fortunate to have some colleagues read the book already. Here is what they had to say about the book:

“From its opening pages, the leading authors guide us through a nuanced engagement with key theoretical ideas about contemporary technological change and the lives of young people subtly synthesised with rich and detailed empirical case studies. This book, set apart from the rest, is tender and responsive to both the participants and the data. It is insightful in quite profound ways. This is a book from which to learn and to change one’s practice as a researcher and a social thinker.” – David Oswell, Professor of Sociology, Goldsmiths, University of London, UK

“From the very first page this compelling polyvocal book bursts with an abundance of detailed conceptual-methodological practices for understanding everyday childhoods and contemporary research. While demonstrating new commitments to the ethical labour required for care in research, it also provides an accessible guide to how we might all enact this in practice. Holding the research archive in mind from the beginning, this book is an instantiation of a transformed research practice, and I cannot wait to see the future archive of research that this text will inspire.” – Niamh Moore, Chancellor’s Fellow and Deputy Director of Research (Ethics), University of Edinburgh, UK

“A fascinating and well-researched look at how kids and teens actually use, understand, and feel about digital media that provides an important counterpoint to moralizing and panic. By listening and working with young people, the authors provide a sorely-needed empirical perspective on a topic often characterized by sensationalism.” – Alice Marwick, Assistant Professor, Media & Technology Studies, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, US

“Set to become the go-to text in how to do qualitative longitudinal research with children and young people. Impeccably written by some of the most prolific scholars in childhood and youth studies, the book offers inspiring, passionate as well as instructive and informative insights into contemporary childhood.” – Sian Lincoln, Reader in Communication, Media and Youth Culture, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

Liam Berriman January 24th, 2018

Posted In: Uncategorized

Leave a Comment

We’re very excited to announce that on 25th January 2018, our new book Researching Everyday Childhoods: Time, Technology and Documentation in a Digital Age will be published with Bloomsbury! (Available to pre-order here.) The book has been co-authored by Rachel Thomson, Liam Berriman and Sara Bragg, and includes contributions from the wider project team and project advisory group.

As well as being published in PB and HB, it will also be available as a gold open access ebook that you can download for free from OAPEN and Bloomsbury Collections.

As a sneak preview, here is the book’s cover and contents page:

Foreword – David Buckingham.

Ch1. Everyday childhoods: Time, technology and documentation – Thomson, Berriman & Bragg.

Ch2. Recipes for documenting everyday lives and times – Thomson with Arnott, Hadfield, Kehily & Sharpe.

Ch3. Protection, participation and ethical labour – Thomson with McGeeney.

Ch4. Spectacles of intimacy: The moral landscape of teenage social media – Berriman & Thomson

Ch5. Materialising time: Toys, memory and Nostalgia – Berriman.

Ch6. The work of gender for children: Now you see it now you don’t – Thomson, Bragg & Kehily.

Ch7. Tracing the affects of contemporary schooling – Bragg.

Ch8. Recipes for co-production with children and young people – Berriman & Howland with Courage.

Ch9. A fellow traveller: The opening of an archive for secondary analysis – Kofoed.

Ch10. Researching as popular and professional practice – Thomson.

Around the book’s release we will be posting a series of blogs that discuss the process of transforming the project from an archive of research materials into a book. These blog posts will provide a ‘making of’ the book, and will aim to provide insight into how our ideas developed in the process of writing and collaboratively theorising the book, as well as exploring the different forms of academic labour entailed in moving from research to publication.

Liam Berriman September 29th, 2017

Posted In: Uncategorized

Leave a Comment

Liam Berriman, Lecturer in Digital Humanities/Social Science

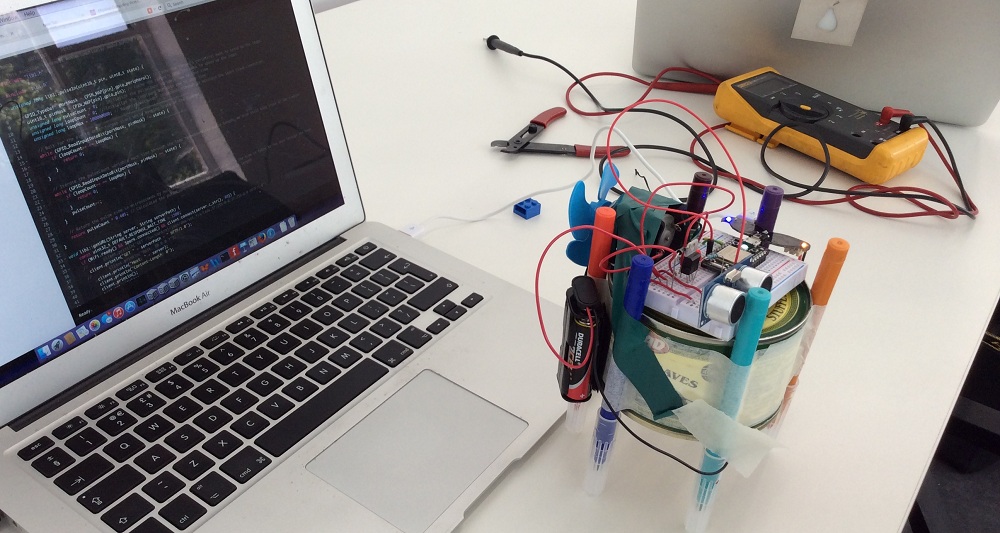

Over the last couple of months I’ve been involved in the development of a project with colleagues at the Sussex Humanities Lab that will look at how we conduct participatory research with children and young people using digital devices. As part of the project we will explore new ways of using different computational methods to ‘hack’ digital devices in order to make participation in research more accessible to different groups of young people. One aspect of this study will look at how we might experiment with the affordances of digital devices as ‘research tools’ in order to re-configure how they are used and the kinds of data they generate.

During the last decade, digital devices have become popular research tools for participatory and ethnographic research with young people. A great deal of participatory youth research now involves researchers and/or participants taking photographs or recording sounds using readily available digital devices, such as mobile phones. Whilst these digital devices have been used to produce a lot of fascinating research on young people’s lives, they often leave open a number of unanswered methodological and ethical questions around the mediatory role of digital devices in research. Here, I want to briefly reflect on three important ways that we need to re-think the role of digital devices in participatory research with young people:

1. Digital devices as ‘black boxes’ – A key challenge of digital devices in research are the way they ‘black box’ the processes of data collection, storage and circulation. Bruno Latour has described how ‘black boxing’ occurs “whenever a piece of machinery or set of commands is too complex” and we (as users) “need to know nothing but its inputs and ouputs” (2000: 681). For the most part, our understanding of how digital devices work, and what they are capable of, is mediated by simplified visual interfaces of menus and settings. Consequently much of the computational complexity of digital devices remains hidden from view, leaving large gaps in our knowledge as to precisely what data are collected (e.g. metadata such as GPS location), how that data is being stored (e.g. local memory or cloud services), and how that data is handled and circulated (e.g. via encrypted or unencrypted channels). These gaps in our knowledge pose significant issues for what role we allow digital devices to play in capturing data that may be ethically sensitive.

Source: https://www.facebook.com/SussexHumanitiesLab/

2. Digital devices as commercial products – Related to the first point, digital devices are commercially manufactured products that have not been designed for use as research tools. As researchers we ‘appropriate’ these devices, drawing on existing affordances of devices (e.g. portability, camera functionality) to facilitate specific research activities. In recent years there have been a number of innovative studies that have creatively appropriated digital devices into research – stretching and subverting their affordances. Nonetheless, the potential uses of these devices for research are by-and-large limited to the parameters set by their consumer-driven design. Consequently, the possibilities for what kinds of data can be generated are often pre-determined and closed down by their design specifications.

3. Digital devices as ‘democratising’ research? – The growing ubiquity and availability of digital devices in everyday life has paved the way for growing numbers of studies that invite participants to capture data about their lives (see for example Wendy Luttrell’s Children Framing Childhoods and Wilson & Milne’s Young People Creating Belonging). In the ‘Face 2 Face’ and ‘Curating Childhood’ studies, we invited young people to record a ‘day in their life’ using either their own digital devices or ones supplied by us. A lingering question from these studies was the extent to which such activities might be seen as ‘democratising’ research and enabling participants to share their lives on their own terms. In particular, the extent to which the parameters of research participation are foreclosed by a particular digital device. In part, this requires a more honest assessment of what forms of research participation digital devices both ‘open up’ and ‘close down’, and how this might vary for different groups of young people taking part in research (e.g. with physical disabilities).

Our study currently under development will explore new ways of ‘opening up’ digital devices within participatory youth research. In order to challenge digital devices as closed data ‘black boxes’, we will seek to explore new participatory research methodologies that involve young people ‘hacking’ research tools and specifying their affordances (such as sensory inputs) for themselves.

Liam Berriman April 23rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: digital data, digital devices, hacking, Liam Berriman, participatory research, Sussex Humanities Lab, youth research

Leave a Comment

Rachel Thomson reflects on her visit to a ‘Toys in the Community’ workshop at the Brighton Toy and Model Museum.

I very much enjoyed a study day at the Brighton Toy & Model Museum showcasing the work of their Heritage Lottery Funded project Toys in the Community which has lots in common with our approach to using ‘favourite things’ as a way of finding out about children’s lives. The overall aim of this project was to encourage community engagement in the toy museum, using a methodology of inviting adults to talk about the toys that they cherished as children – with a focus on teddy bears, dolls and construction toys. These testimonies were filmed and edited and a wonderful website has been developed to showcase the material: http://toysinthecommunity.org/about/

At the study day I met Annebella Pollen who lectures in History of Art and Design at Brighton and was one of the interviewees for the project, where she reflects on her childhood collection of ‘gollys’, black-faced dolls and other memorabilia. Her interview is fascinating, and her presentation pulled out key themes including how ‘unstable’ her memories are of her collection (she can’t actually remember playing with them, just having them). What ‘difficult objects’ they are and were, and how as a child she came to piece together an understanding of the racist discourses that shaped the figure of the golly that she was so attached to. And then the ‘complicated feelings’ that this produced along the way and continues to produce for her today as she reflect on her toys.

A customised Barbie on display at the Brighton Toy Museum

Although this project works with adults, inviting them to reminisce about their childhood through toys, it nevertheless echoes some of the insights that we gained from exploring how children and young people connect with material objects but also how they start feeling nostalgic about them almost from the word ‘go’. For example 7 year old Lucien showed me old toys that captured the kind of boy he used to be (toy cars and a Lego camper van), and teenage Aliyah shared a memory box of memorabilia that she is curating to remember her childhood.

We also saw some of the ways in which toys can be a serious business for children, a way of working out their relationship to a broader culture or simply their place within a household – as wonderfully illustrated by Tempest’s wild doll play.

The study day also confirmed our finding that working with objects can raise powerful emotions and meaning – that we talk about things we have not put into words before as well as recounting well-worn stories. This demands the highest ethical standards for the oral history work, giving people a chance to see their transcripts, to edit material before it goes public and to decide what kinds of formats they want it to be published in. The Toys in the Community project also demonstrated what a popular and participatory methodology this could be, working with a diverse range of groups and ages and involving and training volunteers as interviewers, filmmakers and editors. I especially love the interview between two friends where the creation of an audience allows the couple to find out things about each other that they did not know before.

Liam Berriman April 12th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: archive, everyday, Favourite things, memories, museums, object stories, objects, Rachel Thomson, toys

Leave a Comment

Rachel Thomson, Professor of Childhood and Youth Studies, University of Sussex

I spent a really interesting day at a University of Sussex event in the ESRC funded Digital Bubbles series exploring interdisciplinary perspectives on autism and technology enhanced learning. I was invited as a sociologist to say something about how research into young people’s digital culture can shed light on the wider question and I presented a draft version from our forthcoming book based on the Face to Face and Curating Childhoods project looking at how ‘research’ itself has become an integral part of  young people’s digital cultures: be that obsessing, stalking and fan-girling a band or showing off skills in homework projects. I was given the final slot of the programme which is always a bit gruelling but meant that I had the pleasure of listening to the other contributions of the day.

young people’s digital cultures: be that obsessing, stalking and fan-girling a band or showing off skills in homework projects. I was given the final slot of the programme which is always a bit gruelling but meant that I had the pleasure of listening to the other contributions of the day.

First up was Yvonne Rogers, Professor of Human Computer Interaction at UCL. Whose research involves making things that might disrupt or change the individualising attention economy which she illustrated with a picture of a line of teenagers all staring into smart phones. These are the ‘digital bubbles’ that Yvonne wants to disrupt, encouraging us to ‘look up and out’ from our devices and pay attention to co-presence and face to face interaction. Her amazing projects include wiring up a forest and creating collaborative devices that incite pair collaboration in order to probe and measure the environment, collecting data that can be aggregated and reflect on by the group, revealing new ways of thinking about spaces. Her latest invention are smart cubes that can be coded to respond to movement, heat, moisture and to express sound and colour and to do so relationally via blue tooth. So for example, children could use the cubes as different instruments creating music in real time.

I loved her focus on attention (we are working with Alice Marwick’s idea of the attention economy) and her commitment to use technology deliberately to intervene, enhance and I’d say ‘re-enchant’ face to face interactions. But I did worry about the insularity of the metaphor of the digital bubble. In our research we have become interested in the ways in which technology can enable young people to access new kinds of ‘public’ which may be mediated and ephemeral but can also be networked (boyd) and live (for more see Nolas 2015). Think for example of the groups of friends playing online games together in real time aided by Skype, practicing their wit and repartee.

The intersection of fans, celebrities and ‘professional fans’ in the form of YouTubers (who begin as ordinary fan and turn into celebrities themselves) can be seen as a dynamic cultural circuit that depends on practices of search as well as the production and circulation of content and value by users. It is clearly a great deal of fun, as well as providing opportunities to travel (camping out with fellow fans to see the celebrity and to get a selfie) and to make friends with those beyond your neighbourhood. The question of whether such practices are ‘progressive or reactionary has come to dominate much academic discussion of the phenomena. Some like Jodi Dean suggest that ‘communicative capitalism’ relies on fantasies of participation, contribution and circulation. For Dean these networks are apolitical in that they are contained and literally privatised and their economic value is harvested by advertisers and corporations. Yet there is another tradition of seeing fandom in much more positive terms as a set of social practices, that may well change the world in subtle but profound ways. Synchronicity seems to be an important part of the picture (doing things in unison and in real time) as does co-presence, although whether we need to be in the same room to be co-present is another matter. One of the ideas that we have been playing with is that of ‘sonic bridges’ – the notion that sound has a privileged relationship with togetherness and with synchronicity. Building on Kate Lacey’s ideas of ‘listening’ in and ‘listening out’ perhaps we can play with musical metaphors to think through some of the affordances of the digital for live communications.

To find out more about the seminar and series see http://digitalbubbles.org.uk/?page_id=24

Our book: Researching Everyday Childhoods: Time, Technology and Documentation is forthcoming from Bloomsbury in 2017.

Liam Berriman March 21st, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: autism, digital bubbles, fans, learning, Rachel Thomson, research

Leave a Comment

Dr Liam Berriman, Lecturer in Digital Humanities/Social Science, University of Sussex

In 2007, Savage and Burrows predicted a ‘coming crises of empirical sociology’ as mainstream sociological methods were muscled out by new commercial data analytics techniques. Reflecting on their paper nearly a decade later, they admit that the scale of disruption caused by ‘big data’ (as it is now known) was unimaginable, even at that moment in time (Burrows & Savage 2014).

Our conceptualisation of ‘data’, and the language we use to describe it, have been irreversibly changed by the arrival of big data. For a new breed of data analysts, any dataset that is less than ‘total’ or ‘complete’ has become ‘small data’. The very language of data has been transformed by a new lexicon of analytics, real-time, tracking and scraping etc. However, remaining relatively unchanged is our language for talking about the ethics of ‘big data’.

This short piece focuses on one particular aspect of big data’s methodology – ‘data scraping’ – and the ethical questions it raises for researching young people’s lives through digital data.

According to Marres and Weltevrede (2013), scraping is an ‘automated’ method of capturing online data. It involves a piece of software being programmed (e.g. given instructions) to extract data from a particular source and creating a ‘big’ dataset that would be too onerous to capture manually.

Over the last few years, ‘scraping’ has been much lauded as a means by which data capture can be ‘scaled up’ to new analytical heights, particularly in relation to one of the most popular sources for big data capture – social media. Whilst ‘scraping’ techniques have advanced, a much slower trend has been the discussion of what ethical frameworks and language we need for robustly interrogating these techniques.

As one of the largest constituent users of social media, young people are a particularly relevant group within these debates. Data scraped from social media inevitably captures the conversations, thoughts and expressions of young people’s lives, even if as an ‘inadvertent’ by-product of research.

In 2010, Michael Zimmer reported on a study that had captured the profile data of a whole cohort of American college students on Facebook. The data had been taken without permission and a failure to appropriately anonymise the data had seen the identities of the students revealed. Zimmer’s article provided a robust critique of a growing data capture trend where all data not hidden by privacy settings was seen as consensually ‘public’, and available for analysis.

The ethical lessons learnt from incidents such as these have tended to focus more on greater care for data anonymization and security, and less on issues of consent and intrusion. Again, Zimmer (2010) has been particularly vocal in refuting claims that techniques such as anonymization through aggregation are ‘enough’[1].

How do these debates connect with young people’s social media data? Television programmes such as Teens and The Secret Life of Students[2] have played a significant role in perpetuating the idea that young people are less concerned than adults about having their data made public. However, studies have repeatedly shown that young people are highly concerned about privacy online (boyd, 2014; Berriman & Thomson, 2015), and the disclosure of their digital data (Bryce & Fraser, 2014).

A little while ago, I became aware that ‘scraping’ has a colloquial meaning in some UK secondary schools. According to Urban Dictionary (think Wikipedia for slang terms and phrases), the term ‘scrape’ is used to describe:

a person intruding on something. To say that one has come out of nowhere and intruded on a conversation.

[E.g.] ‘two people have a conversation’, ‘another person listens in’

one person out the original two people says “scrape out” to the other person.

This colloquial definition makes reference to ‘scraping’ as an unwelcome form of eavesdropping and intrusion on a private conversation. In the context of these ethical discussions, this definition seems particularly apt. It emphasises that privacy is a concern for young people, and that unsolicited ‘scraping’ of private conversations is ethically and morally contentious.

At present, there is a lack of serious ethical debate about the scraping of young people’s digital data. The presumption of public-as-consent doesn’t cut it. We need a new ethical language for talking about these issues, and young people’s voices need to be represented in these debates.

[1] Indeed, how ‘successful’ these techniques are remains debateable – see Ars Technica, 2009

[2] Two documentary series by production company Raw for Channel 4 that followed young people’s social media lives by harvesting their Tweets, texts, and Facebook updates.

Liam Berriman February 23rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: automation, big data, crises, digital data, ethics, Liam Berriman, scraping

Leave a Comment

In the second of a series of blog posts, Suzanne Rose and Anthony McCoubrey from the Mass Observation Archive reflect on their participation in the ESRC Festival of Social Science event: the ‘My Object Stories’ Hackathon and the significance of ‘object stories’ for the Archive.

This was the third year in a row that the Mass Observation Archive (MOA) has taken part in the ESRC Festival of Social Science, which takes place nationally to promote social science research to non-academic communities and the wider public. The MOA hosted two events, which were part of a programme of over 200 events taking place across the country celebrating the social sciences.

‘Mo’, the Mass Observation Archive’s teddy bear mascot, volunteers to pilot the fiducial tracker.

This year our events we focused on engaging young people with the MOA and considered how archives relate to the digital age. One event was a day long workshop for pupils from Ratton School at the MOA at The Keep and the other was the My Object Stories Hackathon. This was designed to be a public event targeting young people, which would provide an opportunity for them to develop their understanding of the MOA and experiment with digital technology.

Working in partnership with CIRCY, the Department of Social Work and UoS Humanities Lab, provided a fantastic opportunity to engage the young people with the latest technologies and to invite them to share their objects and their stories with the archive in unique and interesting ways.

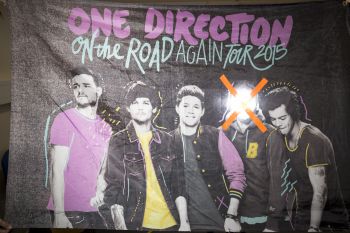

The young people who took part in the Hackathon were asked to bring an object with them, which had a particular significance to them and to share their story with the team. They brought a range of objects with them, from a One Direction flag, favourite bo

oks, plastic animals and a guitar and even a pair of Dr Martens boots and all had a personal story to share. These object stories were captured through discussion with the young people, before being presented to be photographed and interviewed and recorded, before being transformed into a digital installation by colleagues much techier than myself.

I really enjoyed working with the young people to find out about their objects and explore their stories. So much of what we hold in the Mass Observation Archive is peoples’ stories and so it was really exciting to be working with  young people who were eager to share their stories with us.

young people who were eager to share their stories with us.

The objects they chose were also very interesting and of their time with particular personal significance attached and the young people spoke very thoughtfully about why they had chosen their object and what it meant to them.

Some objects such as the One Direction flag were especially timely, given the bands recent loss of member Zayn Malik and decision to take time out from performing. This marks a significant event in the lives of many Directioners and something which should be captured in the archive.

Other objects were more timeless, such as the Dr Martens boots, which marked the connection between the present day and generations of people who have loved and worn them over time. The young person spoke about how her mum had also collected DM boots in her youth and so this object also had significance for her and her family and traditions within it.

Objects are often held onto for very personal reasons and we were very privileged that the young people felt able to share their stories with us and that these stories and their significance will be captured for the archive collection.

Within the next few months we look forward to presenting the a roundup of the Hackathon’s events in an installation and inviting the young people back to see their amazing contribution as well as depositing some of the photographs and recordings in the Everyday Childhood Collection at archive collections at The Keep.

Liam Berriman January 12th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: Anthony McCoubrey, archive, everyday, Favourite things, hackathon, Mass Observation, object stories, Sussex Humanities Lab, Suzanne Rose

Leave a Comment

In the first of a series of blogs, researchers Rachel Thomson and Liam Berriman reflect on how hackathons might be used as a participatory methodology that span the digital humanities, social science, design and computing.

Talk to me.

Rachel Thomson

On Saturday 14th November I had the pleasure of taking part in an event billed as a ‘Hackathon’ hosted by the Sussex Humanities Lab, CIRCY and the Mass Observation Archive. Hackathons are ‘events in which computer programmers and others involved in software development and hardware development, including graphic designers, interface designers and project managers, collaborate intensively on software projects’.

The day was called ‘my object stories’ and the shared project was to explore ways in which we could bring to life young people’s stories about favourite everyday objects – building on work that we have been doing as part of the Curating Childhoods project which is creating a new multi-media collection within Mass Observation called ’Everyday Childhoods’. The shared task was to invent strategies through which everyday objects – cherished by young people – might talk to an audience and enrich the archive. This might be a pair of Dr Martens boots, a book, a guitar, plastic animals….

Often projects are done in separate stages, with people responsible for their ‘bit’. The hackathon model brought together all the different actors involved in the lifecycle of a research and development project to see what we could get done in a day. In this way, the event created a live interface between processes of data collection, archiving and animation.

The day started and ended with the archive. Young people brought in cherished objects to share as windows into their everyday lives. Researchers and archive outreach officers worked with them to brainstorm what they might want to say about their objects. Photographer Crispin Hughes then collaborated with them to design still images that captured their object, and film maker Susi Arnott recorded them talking about their object’s value and personal meaning.

The digital data was then sent downstairs into the lab where they were used as raw materials for three different data animation strategies. Ben Jackson and Cathy Grundy brought images and sound together within a augmented reality environment – creating short animated films. Manuel Cruz used Unity game design software to make simple games through which a player could encounter objects and stories as part of game pl ay. Chris Kiefer and Thanos Liontiris used motion tracking technology (cameras trained on a fiducial) hooked up to two different platforms: supercollider, through which sound could be triggered by movement, and a second platform which managed visual data projected onto a table acting as a screen. This meant that the object could be moved through a space – with the movements used to reveal images and sound. Young people came down and worked on shaping the three different versions of their object stories.

ay. Chris Kiefer and Thanos Liontiris used motion tracking technology (cameras trained on a fiducial) hooked up to two different platforms: supercollider, through which sound could be triggered by movement, and a second platform which managed visual data projected onto a table acting as a screen. This meant that the object could be moved through a space – with the movements used to reveal images and sound. Young people came down and worked on shaping the three different versions of their object stories.

What I liked most about the day was the way in which all the different ‘experts’ involved got to check out what each other do. I was probably very annoying, looking over shoulders, interrupting and asking questions and no doubt slowed things down. In a day we managed to get a lot done, though nothing ‘finished’. However we did manage to imagine three different ways in which the ‘show and tell’ of research might be achieved in collaboration with digital design. Each of the strategies could provide an interface through which archived data could be accessed and mediated.

The archivists had a think about how the audio and visual data might be cataloged in the archive and spoke with the developers and the researchers about how their different approaches to organising the material might relate. We also gained insight into the kind of work that might be involved in each of the strategies for animation, providing insights for costing future projects.

The day formed part of an ESRC festival of social science, showcasing to the public the relevance and potential of social research. Our aim was to open up the process through which researchers may co-produce ‘data’ with young participants and to explore the way in which this might be re-used and brought to life in different ways. Building on our earlier work with Mass Observation we wanted to show that an archive need not be seen as a dusty and distant place, but rather the starting point for a range of creative engagements. What is brilliant about the Mass Observation Archive is that it celebrates the mundane and the everyday, believing that in ten, fifty, one-hundred years time people will be as fascinated by hearing about a pair of Dr Marten boots – as we are now excited to know about what people had in their wardrobes in 1945. But the hackathon helped us glimpse how we might use this material right here and now as a starting point in creative experiments with ‘data’.

Hackathons as participatory methodology?

Liam Berriman

Hackathons have become an increasingly commonplace methodology for exploring and experimenting with data. Recent examples of this trend have included calls from archives for programmers and software developers to come and ‘hack’ their collections, and the growth of competitions where young people are invited to play with open-access datasets. Bridging these events is a growing sense of hackathons as a space for playing with archives and data.

The ‘My Object Stories’ workshop was my first experience of organising (and taking part in!) a hackathon. Over the past year, I’ve become interested in hackathons as a methodology for engaging young people with their own research data – providing a creative space for playing with the re-animation (or ‘hacking’) of data (McGeeney, 2014). Hackathons are often billed as collaborative events that draw on the participation and collective skills of all involved, and i’ve been curious about how hackathons might be used to engage young people in research beyond the data collection process.

The ‘My Object Stories’ workshop was my first experience of organising (and taking part in!) a hackathon. Over the past year, I’ve become interested in hackathons as a methodology for engaging young people with their own research data – providing a creative space for playing with the re-animation (or ‘hacking’) of data (McGeeney, 2014). Hackathons are often billed as collaborative events that draw on the participation and collective skills of all involved, and i’ve been curious about how hackathons might be used to engage young people in research beyond the data collection process.

Though excited by the creative possibilities that hackathons open up, I’ve remained cautious about overstating their potential as ‘participatory’ methods. In past research I’ve voiced scepticism about co-design practices with young people that claim to be participatory. My main concern being that researchers and designers have become very good at speaking the discourse of participation, but are often uncritical about participation’s potential ‘unevenness’ in practice (Berriman, 2014). As such, I approached this event as an experiment in data collection and re-animation, but also as an event in need of critical reflection.

In many ways our hackathon was atypical in format, with the young people creating the data to be ‘hacked’. This created an intensely personal connection between the young people and the hackathon data, with each participant principally concerned with hacking their own data. One of the main challenges this raised was in terms of equipping each young person with the skills and resources to ‘make something’ of their data. Our adult hacker team were on hand to help guide participants through possible data re-animation techniques of varying complexity (ranging from free app tools to game design engines.) The hackathon’s collective expertise and interests therefore played a significant role in defining the potential scope of data animation activities.

The hackathon is therefore a highly situated event that is contingent upon the collaborative pooling of expertise around a common project. Participation is characterised less by unbridled creativity, and more by a curiosity to explore what was possible in a space of assorted interests and expertise. In this respect, the hackathon provides us with a method for engineering collaborative spaces where people with different skills and expertise can come together to experiment with new ways of playing with data.

To find out more about the My Object Stories Hackathon, contact Liam Berriman (l.j.berriman@sussex.ac.uk)

The My Object Stories Hackathon was co-hosted by the Sussex Humanities Lab, the Mass Observation Archive, and the Centre for Innovation and Research in Childhood and Youth. It was funded with support from the ESRC Festival of Social Science and the EPSRC Cultures and Communities Network +.

Liam Berriman December 11th, 2015

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: archive, everyday, Favourite things, hackathon, Liam Berriman, Mass Observation, object stories, Rachel Thomson, Sussex Humanities Lab

One Comment

Prof Rachel Thomson

You notice things at festivals, at the meeting point of genres and cultural forms: music, comedy, literature, performance. One of the things I noticed this summer was how participation seems to be infusing them all. In the theatre they talk about the 4th wall, the ‘make believe’ suspension of reality that enables us to unleash our imaginations without fear of ridicule or danger. The 4th wall exists in music too. Salt-N-Pepa’s 1991 single “Let’s Talk About Sex” says “I don’t think this song’s going to be played on the radio”. John Cage’s 4 minutes and 33 seconds of silence demands we face the collaborative artifice of performance. A popular practice is to experiment along the boundaries of constructed-ness: fact, fiction, real time and the imaginative time travel. In the fabulous 12-year in-gestation ‘Boyhood’, Richard Linklater mixes up the meanings of family, friends and actors revealing the compelling and forward facing time frame within which we all exist and age, and within which culture gains audience and meaning. A space within which we build culture and community through call and response.

I am writing this on the train to London as I go to interview Lucien, whose life I have been documenting since before he was born. One of my aims today is to talk to him about what being involved in this study means, ensuring that his ‘consent’ is meaningful. His mum and I share cultural references. When I explained the nature of a longitudinal study I used the ‘7 up’ metaphor, the now-classic ongoing documentary series that seems to have become the key text of reflexive modernity: providing a vocabulary for understanding reality tv (the politics of editing), the emotional economies of public exposure (the more powerful withdrew) and the peculiar moral register of the real time voyeurism (we are implicated for good or bad). So when I asked Monica, 8-months pregnant, if she wanted to be in a longitudinal study she had this as a reference point. For Lucien things are different, especially in the early stages, but as a culture-savvy-in-no-hurry kid, he can place this experience alongside others – the homework projects that require a life story, YouTube stars who document their lives online, or just the long running tv shows like Dr Who and Top Gear where we see characters age and where real life scandal get folded into the cultural product.

But this is research…. I was tempted to write ‘research rather than entertainment’. I could also say ‘rather than documentary’ or more pertinently for Lucien ‘rather than play’, but I am not sure that research should be set up in this way. Research is defined by the presence of research questions and an interest in methodology – a plan for HOW to generate answers to these questions. But research is still part of life. It has its own fourth wall. What we are doing is ‘for research’ so, for example, we will call our interaction an ‘interview’, and this means that we do not have to follow the usual unwritten rules of conversation. Or we will call this an ‘observation’ and this means that I have license to spend the day with you, acting as a shadow, giving myself over to noticing the sounds, smells and sensations of your life.

Research ethics – as conceived through the adult subject – presume a tacit agreement to the terms of this game and the validity of the 4th wall. It is this that we ask our ‘subjects’ (the old language) or ‘participants’ (the new language) to consent to. I sign on this line to agree to take part in a conversation that is of a different order of things than usual life. This means that the researcher may have more power than is usual and I need to trust them not to hurt me or to use the knowledge that we together create as a result of our experiment in a way that might be disrespectful or damaging to me or, for that matter, others. With children who are used to slipping in and out of play mode, this ‘contract’ becomes rather ridiculous. In a healthy way it pushes us towards a different kind of gambit along the lines of ‘I am an adult who would really like to play with you. The reason for this is that I recognise that playing is a really good way of creating knowledge and understanding. Mostly you play with other kids, but also with adults, maybe parents and teachers. What is different with this is that I am going to make documents of our play together and these will be public. Which means that other people can see them. But also you can go back to them over time and they, unlike you, will not change. This might be odd. We’d like you to say yes to doing this. But given that neither of us really know what will happen in the future we are willing to negotiate over the documents. This means you can change your mind and that the records belong to both of us.’

Working with children, as actors know, has a special quality. Perhaps because the 4th wall is something that we have to be socialised into and which symbolically marks the end of an enchanted period of childhood in which the imagination is allowed full rein. The 4th wall is also a historically located phenomena – a product of a particular form of technology and associated literacies. Digital technologies change the game and new generations are taking new things for granted. Of course this poses challenges for research which relies on an analogue-ethics concerned with risk avoidance rather than participation. Working with ideas such as call and response and the power dynamics of the porous 4th wall may help us play.

Liam Berriman December 4th, 2014

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: 4th wall, consent, ethics, qualitative longitudinal, Rachel Thomson

Leave a Comment

young people’s digital cultures: be that obsessing, stalking and fan-girling a band or showing off skills in homework projects. I was given the final slot of the programme which is always a bit gruelling but meant that I had the pleasure of listening to the other contributions of the day.

young people’s digital cultures: be that obsessing, stalking and fan-girling a band or showing off skills in homework projects. I was given the final slot of the programme which is always a bit gruelling but meant that I had the pleasure of listening to the other contributions of the day.