By Victoria Grace Walden, Senior Lecturer, Director of Learning Enhancement

So often online learning is discussed as a ‘deficit’ model (Darabi et al 2010, 216). It is compared to in-person, campus teaching, which it can never be identical too, therefore it is perceived as lesser. Critical digital pedagogues, Maha Bali and Bard Meier (2014), however, argue that presumptions that online learning should look like in-person learning are informed by three (incorrect) assumptions:

- ‘that text is less personal’ [than audio-visual]

- ‘that immediacy is inherently more valuable’ [than asynchronous]

- ‘and that approximating face-to-face is beneficial’.

They celebrate asynchronous learning for the ways it promotes ‘deeper reflection’, during which powerful learning is happening; it is just learning that the instructor cannot see or monitor.

In August 2021, I had the pleasure of attending the Digital Pedagogy Lab , founded by Sean Michael Morris with threads by a variety of contributors, including Bali. Morris, Bali and colleagues run the Hybrid Pedagogy open journal, which focuses on Critical Digital Pedagogy – heavily influenced by bell hooks, Paulo Freire, and Henry Giroux. Essentially, the work of the journal emphasises the humanness at the centre of (digital) learning.

Media Education Theorist, Julian McDougall, argues ‘that online learning spaces can be productive “third spaces” if they are charged with creative, productive possibilities, combined with an ethnographic turn in curriculum design’ (2021, 2). He argues against the idea of online learning spaces providing ‘supplementary’ materials to the physical classroom (2021, 3). Instead, following thinkers like Bali, he suggests a need to think about how students’ personal learning journeys might take shape across, through, and combining different spaces.

Another influence on McDougall’s work is that of Arndt et al. (2020), who argue that online higher education, just as with offline, needs to be understood as relational, which emphasises the ethics embedded in learning design. In this sense, notions of student ‘engagement’ and ‘presence’ refer to how their ‘relational energy’ is generated through their personal learning journey (McDougall 2021, 25).

As we transitioned back to on-campus teaching as the dominant form of engagement with students, I wanted to think about what I could take form my experiences of remote, online teaching during the pandemic to inform an inclusive, blended approach going forward. I was conscious that not all of our students would be able to be on campus for the entire term – how could I created a learning experience that was as accessible as possible to all students?

What I did

Design your own blended learning journey

Acknowledging that each student will create their own personal journey through the module, I decided to design each week with a ‘menu’ of learning options (some online and collaborative; some online and solo; some offline and solo; some on campus together). Each week was divided into five sections:

Challenge Yourself to Learn Something New

- Complete the readings.

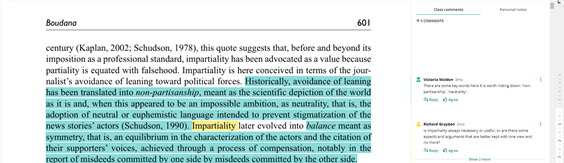

- Engage in asynchronous reading discussions using Talis Elevate through questions I tagged to certain places in the readings or download the readings and look at them independently.

- Attend the seminar, lecture and workshop this week.

Check your Learning

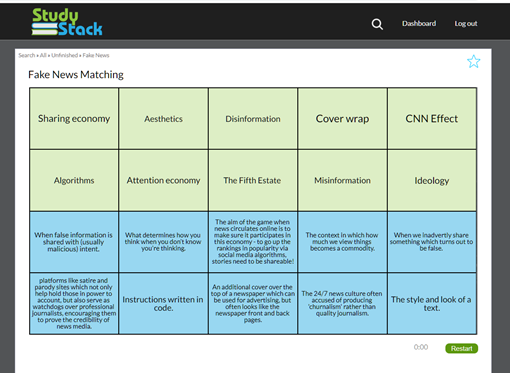

- Review or contribute to the weekly glossary.

- Test your knowledge of terminology using games on Study Stack

Practice

- Complete the weekly thematic task, such as log your engagements with news (Week 1). This gave space for quiet, offline, solo work.

Engage with your Learning Community

- Discuss readings on Talis Elevate.

- Participate in discussion forms.

- Add questions or your own case studies in advance to each seminar group’s Padlet.

- Meet with your study group online or offline to discuss your practice task(s).

Reflect on your Learning

- Reflection questions and tasks to guide students to creating and maintaining goals, such as creating their own study schedule to project manage their own learning.

In structuring support for students’ personal learning journey, I wanted to ensure that tasks were not divided into in-person or offline tasks, and online learning. I also wanted to avoid the idea that online learning is supplementary to offline. The use of headings designed to encourage challenge, assessment, practice, community, and reflection were the driving forces under which a range of online and offline activities were included.

Using the UK Professional Standards Framework (PSF) to ensure good practice and excellent student experience. This teaching practice outlined in this blog post is informed by the highlighted areas:

Areas of activity

- A1 Design and plan learning activities and/or programmes of study

- A2 Teach and/or support learning

- A3 Assess and give feedback to learners

- A4 Develop effective learning environments and approaches to student support and guidance

- A5 Engage in continuing professional development in subjects/disciplines and their pedagogy, incorporating research, scholarship and the evaluation of professional practices

Core knowledge

- K1 The subject material

- K2 Appropriate methods for teaching, learning and assessing in the subject area and at the level of the academic programme

- K3 How students learn, both generally and within their subject/ disciplinary area(s)

- K4 The use and value of appropriate learning technologies

- K5 Methods for evaluating the effectiveness of teaching

- K6 The implications of quality assurance and quality enhancement for academic and professional practice with a particular focus on teaching

Professional values

- V1 Respect individual learners and diverse learning communities

- V2 Promote participation in higher education and equality of opportunity for learners

- V3 Use evidence-informed approaches and the outcomes from research, scholarship and continuing professional development

- V4 Acknowledge the wider context in which higher education operates recognising the implications for professional practice

Leave a Reply