Rachel Thomson reflects on her visit to a ‘Toys in the Community’ workshop at the Brighton Toy and Model Museum.

I very much enjoyed a study day at the Brighton Toy & Model Museum showcasing the work of their Heritage Lottery Funded project Toys in the Community which has lots in common with our approach to using ‘favourite things’ as a way of finding out about children’s lives. The overall aim of this project was to encourage community engagement in the toy museum, using a methodology of inviting adults to talk about the toys that they cherished as children – with a focus on teddy bears, dolls and construction toys. These testimonies were filmed and edited and a wonderful website has been developed to showcase the material: http://toysinthecommunity.org/about/

At the study day I met Annebella Pollen who lectures in History of Art and Design at Brighton and was one of the interviewees for the project, where she reflects on her childhood collection of ‘gollys’, black-faced dolls and other memorabilia. Her interview is fascinating, and her presentation pulled out key themes including how ‘unstable’ her memories are of her collection (she can’t actually remember playing with them, just having them). What ‘difficult objects’ they are and were, and how as a child she came to piece together an understanding of the racist discourses that shaped the figure of the golly that she was so attached to. And then the ‘complicated feelings’ that this produced along the way and continues to produce for her today as she reflect on her toys.

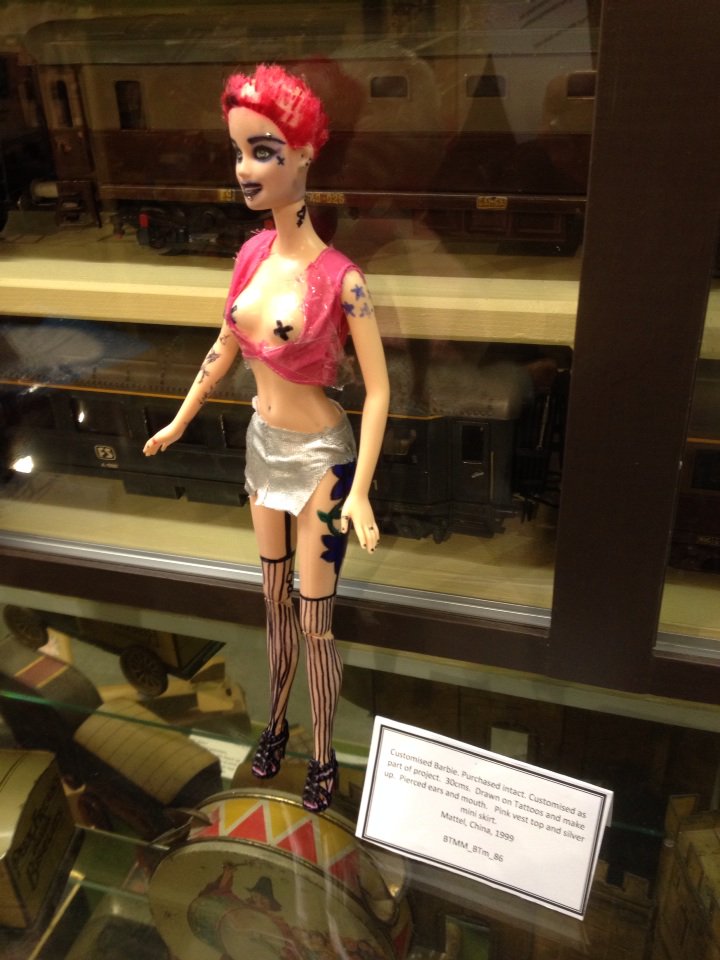

A customised Barbie on display at the Brighton Toy Museum

Although this project works with adults, inviting them to reminisce about their childhood through toys, it nevertheless echoes some of the insights that we gained from exploring how children and young people connect with material objects but also how they start feeling nostalgic about them almost from the word ‘go’. For example 7 year old Lucien showed me old toys that captured the kind of boy he used to be (toy cars and a Lego camper van), and teenage Aliyah shared a memory box of memorabilia that she is curating to remember her childhood.

We also saw some of the ways in which toys can be a serious business for children, a way of working out their relationship to a broader culture or simply their place within a household – as wonderfully illustrated by Tempest’s wild doll play.

The study day also confirmed our finding that working with objects can raise powerful emotions and meaning – that we talk about things we have not put into words before as well as recounting well-worn stories. This demands the highest ethical standards for the oral history work, giving people a chance to see their transcripts, to edit material before it goes public and to decide what kinds of formats they want it to be published in. The Toys in the Community project also demonstrated what a popular and participatory methodology this could be, working with a diverse range of groups and ages and involving and training volunteers as interviewers, filmmakers and editors. I especially love the interview between two friends where the creation of an audience allows the couple to find out things about each other that they did not know before.

Liam Berriman April 12th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: archive, everyday, Favourite things, memories, museums, object stories, objects, Rachel Thomson, toys

Leave a Comment

In the second of a series of blog posts, Suzanne Rose and Anthony McCoubrey from the Mass Observation Archive reflect on their participation in the ESRC Festival of Social Science event: the ‘My Object Stories’ Hackathon and the significance of ‘object stories’ for the Archive.

This was the third year in a row that the Mass Observation Archive (MOA) has taken part in the ESRC Festival of Social Science, which takes place nationally to promote social science research to non-academic communities and the wider public. The MOA hosted two events, which were part of a programme of over 200 events taking place across the country celebrating the social sciences.

‘Mo’, the Mass Observation Archive’s teddy bear mascot, volunteers to pilot the fiducial tracker.

This year our events we focused on engaging young people with the MOA and considered how archives relate to the digital age. One event was a day long workshop for pupils from Ratton School at the MOA at The Keep and the other was the My Object Stories Hackathon. This was designed to be a public event targeting young people, which would provide an opportunity for them to develop their understanding of the MOA and experiment with digital technology.

Working in partnership with CIRCY, the Department of Social Work and UoS Humanities Lab, provided a fantastic opportunity to engage the young people with the latest technologies and to invite them to share their objects and their stories with the archive in unique and interesting ways.

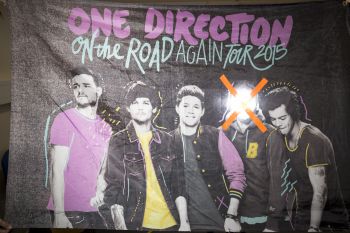

The young people who took part in the Hackathon were asked to bring an object with them, which had a particular significance to them and to share their story with the team. They brought a range of objects with them, from a One Direction flag, favourite bo

oks, plastic animals and a guitar and even a pair of Dr Martens boots and all had a personal story to share. These object stories were captured through discussion with the young people, before being presented to be photographed and interviewed and recorded, before being transformed into a digital installation by colleagues much techier than myself.

I really enjoyed working with the young people to find out about their objects and explore their stories. So much of what we hold in the Mass Observation Archive is peoples’ stories and so it was really exciting to be working with  young people who were eager to share their stories with us.

young people who were eager to share their stories with us.

The objects they chose were also very interesting and of their time with particular personal significance attached and the young people spoke very thoughtfully about why they had chosen their object and what it meant to them.

Some objects such as the One Direction flag were especially timely, given the bands recent loss of member Zayn Malik and decision to take time out from performing. This marks a significant event in the lives of many Directioners and something which should be captured in the archive.

Other objects were more timeless, such as the Dr Martens boots, which marked the connection between the present day and generations of people who have loved and worn them over time. The young person spoke about how her mum had also collected DM boots in her youth and so this object also had significance for her and her family and traditions within it.

Objects are often held onto for very personal reasons and we were very privileged that the young people felt able to share their stories with us and that these stories and their significance will be captured for the archive collection.

Within the next few months we look forward to presenting the a roundup of the Hackathon’s events in an installation and inviting the young people back to see their amazing contribution as well as depositing some of the photographs and recordings in the Everyday Childhood Collection at archive collections at The Keep.

Liam Berriman January 12th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: Anthony McCoubrey, archive, everyday, Favourite things, hackathon, Mass Observation, object stories, Sussex Humanities Lab, Suzanne Rose

Leave a Comment

In the first of a series of blogs, researchers Rachel Thomson and Liam Berriman reflect on how hackathons might be used as a participatory methodology that span the digital humanities, social science, design and computing.

Talk to me.

Rachel Thomson

On Saturday 14th November I had the pleasure of taking part in an event billed as a ‘Hackathon’ hosted by the Sussex Humanities Lab, CIRCY and the Mass Observation Archive. Hackathons are ‘events in which computer programmers and others involved in software development and hardware development, including graphic designers, interface designers and project managers, collaborate intensively on software projects’.

The day was called ‘my object stories’ and the shared project was to explore ways in which we could bring to life young people’s stories about favourite everyday objects – building on work that we have been doing as part of the Curating Childhoods project which is creating a new multi-media collection within Mass Observation called ’Everyday Childhoods’. The shared task was to invent strategies through which everyday objects – cherished by young people – might talk to an audience and enrich the archive. This might be a pair of Dr Martens boots, a book, a guitar, plastic animals….

Often projects are done in separate stages, with people responsible for their ‘bit’. The hackathon model brought together all the different actors involved in the lifecycle of a research and development project to see what we could get done in a day. In this way, the event created a live interface between processes of data collection, archiving and animation.

The day started and ended with the archive. Young people brought in cherished objects to share as windows into their everyday lives. Researchers and archive outreach officers worked with them to brainstorm what they might want to say about their objects. Photographer Crispin Hughes then collaborated with them to design still images that captured their object, and film maker Susi Arnott recorded them talking about their object’s value and personal meaning.

The digital data was then sent downstairs into the lab where they were used as raw materials for three different data animation strategies. Ben Jackson and Cathy Grundy brought images and sound together within a augmented reality environment – creating short animated films. Manuel Cruz used Unity game design software to make simple games through which a player could encounter objects and stories as part of game pl ay. Chris Kiefer and Thanos Liontiris used motion tracking technology (cameras trained on a fiducial) hooked up to two different platforms: supercollider, through which sound could be triggered by movement, and a second platform which managed visual data projected onto a table acting as a screen. This meant that the object could be moved through a space – with the movements used to reveal images and sound. Young people came down and worked on shaping the three different versions of their object stories.

ay. Chris Kiefer and Thanos Liontiris used motion tracking technology (cameras trained on a fiducial) hooked up to two different platforms: supercollider, through which sound could be triggered by movement, and a second platform which managed visual data projected onto a table acting as a screen. This meant that the object could be moved through a space – with the movements used to reveal images and sound. Young people came down and worked on shaping the three different versions of their object stories.

What I liked most about the day was the way in which all the different ‘experts’ involved got to check out what each other do. I was probably very annoying, looking over shoulders, interrupting and asking questions and no doubt slowed things down. In a day we managed to get a lot done, though nothing ‘finished’. However we did manage to imagine three different ways in which the ‘show and tell’ of research might be achieved in collaboration with digital design. Each of the strategies could provide an interface through which archived data could be accessed and mediated.

The archivists had a think about how the audio and visual data might be cataloged in the archive and spoke with the developers and the researchers about how their different approaches to organising the material might relate. We also gained insight into the kind of work that might be involved in each of the strategies for animation, providing insights for costing future projects.

The day formed part of an ESRC festival of social science, showcasing to the public the relevance and potential of social research. Our aim was to open up the process through which researchers may co-produce ‘data’ with young participants and to explore the way in which this might be re-used and brought to life in different ways. Building on our earlier work with Mass Observation we wanted to show that an archive need not be seen as a dusty and distant place, but rather the starting point for a range of creative engagements. What is brilliant about the Mass Observation Archive is that it celebrates the mundane and the everyday, believing that in ten, fifty, one-hundred years time people will be as fascinated by hearing about a pair of Dr Marten boots – as we are now excited to know about what people had in their wardrobes in 1945. But the hackathon helped us glimpse how we might use this material right here and now as a starting point in creative experiments with ‘data’.

Hackathons as participatory methodology?

Liam Berriman

Hackathons have become an increasingly commonplace methodology for exploring and experimenting with data. Recent examples of this trend have included calls from archives for programmers and software developers to come and ‘hack’ their collections, and the growth of competitions where young people are invited to play with open-access datasets. Bridging these events is a growing sense of hackathons as a space for playing with archives and data.

The ‘My Object Stories’ workshop was my first experience of organising (and taking part in!) a hackathon. Over the past year, I’ve become interested in hackathons as a methodology for engaging young people with their own research data – providing a creative space for playing with the re-animation (or ‘hacking’) of data (McGeeney, 2014). Hackathons are often billed as collaborative events that draw on the participation and collective skills of all involved, and i’ve been curious about how hackathons might be used to engage young people in research beyond the data collection process.

The ‘My Object Stories’ workshop was my first experience of organising (and taking part in!) a hackathon. Over the past year, I’ve become interested in hackathons as a methodology for engaging young people with their own research data – providing a creative space for playing with the re-animation (or ‘hacking’) of data (McGeeney, 2014). Hackathons are often billed as collaborative events that draw on the participation and collective skills of all involved, and i’ve been curious about how hackathons might be used to engage young people in research beyond the data collection process.

Though excited by the creative possibilities that hackathons open up, I’ve remained cautious about overstating their potential as ‘participatory’ methods. In past research I’ve voiced scepticism about co-design practices with young people that claim to be participatory. My main concern being that researchers and designers have become very good at speaking the discourse of participation, but are often uncritical about participation’s potential ‘unevenness’ in practice (Berriman, 2014). As such, I approached this event as an experiment in data collection and re-animation, but also as an event in need of critical reflection.

In many ways our hackathon was atypical in format, with the young people creating the data to be ‘hacked’. This created an intensely personal connection between the young people and the hackathon data, with each participant principally concerned with hacking their own data. One of the main challenges this raised was in terms of equipping each young person with the skills and resources to ‘make something’ of their data. Our adult hacker team were on hand to help guide participants through possible data re-animation techniques of varying complexity (ranging from free app tools to game design engines.) The hackathon’s collective expertise and interests therefore played a significant role in defining the potential scope of data animation activities.

The hackathon is therefore a highly situated event that is contingent upon the collaborative pooling of expertise around a common project. Participation is characterised less by unbridled creativity, and more by a curiosity to explore what was possible in a space of assorted interests and expertise. In this respect, the hackathon provides us with a method for engineering collaborative spaces where people with different skills and expertise can come together to experiment with new ways of playing with data.

To find out more about the My Object Stories Hackathon, contact Liam Berriman (l.j.berriman@sussex.ac.uk)

The My Object Stories Hackathon was co-hosted by the Sussex Humanities Lab, the Mass Observation Archive, and the Centre for Innovation and Research in Childhood and Youth. It was funded with support from the ESRC Festival of Social Science and the EPSRC Cultures and Communities Network +.

Liam Berriman December 11th, 2015

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: archive, everyday, Favourite things, hackathon, Liam Berriman, Mass Observation, object stories, Rachel Thomson, Sussex Humanities Lab

One Comment

Dr Liam Berriman

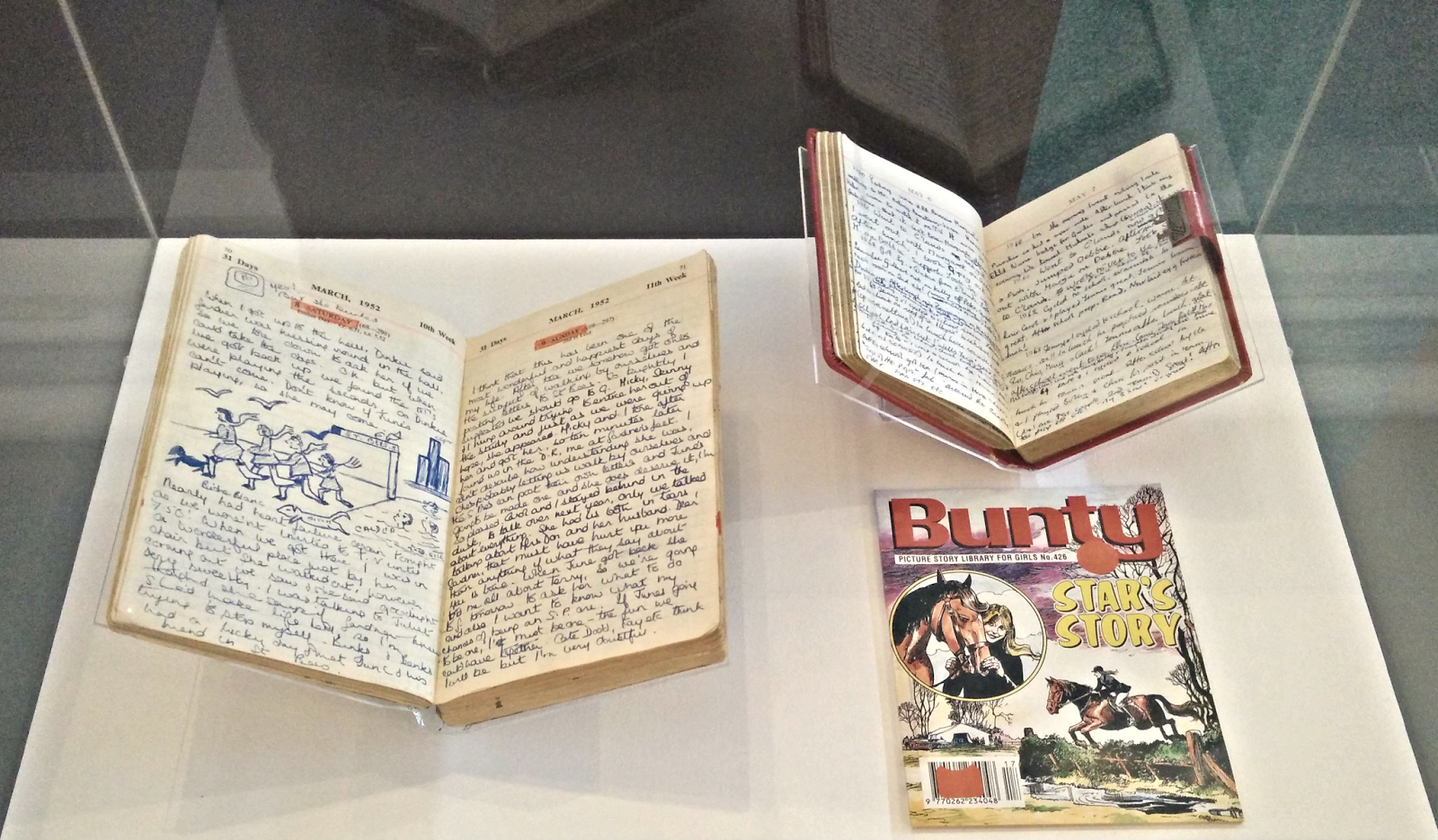

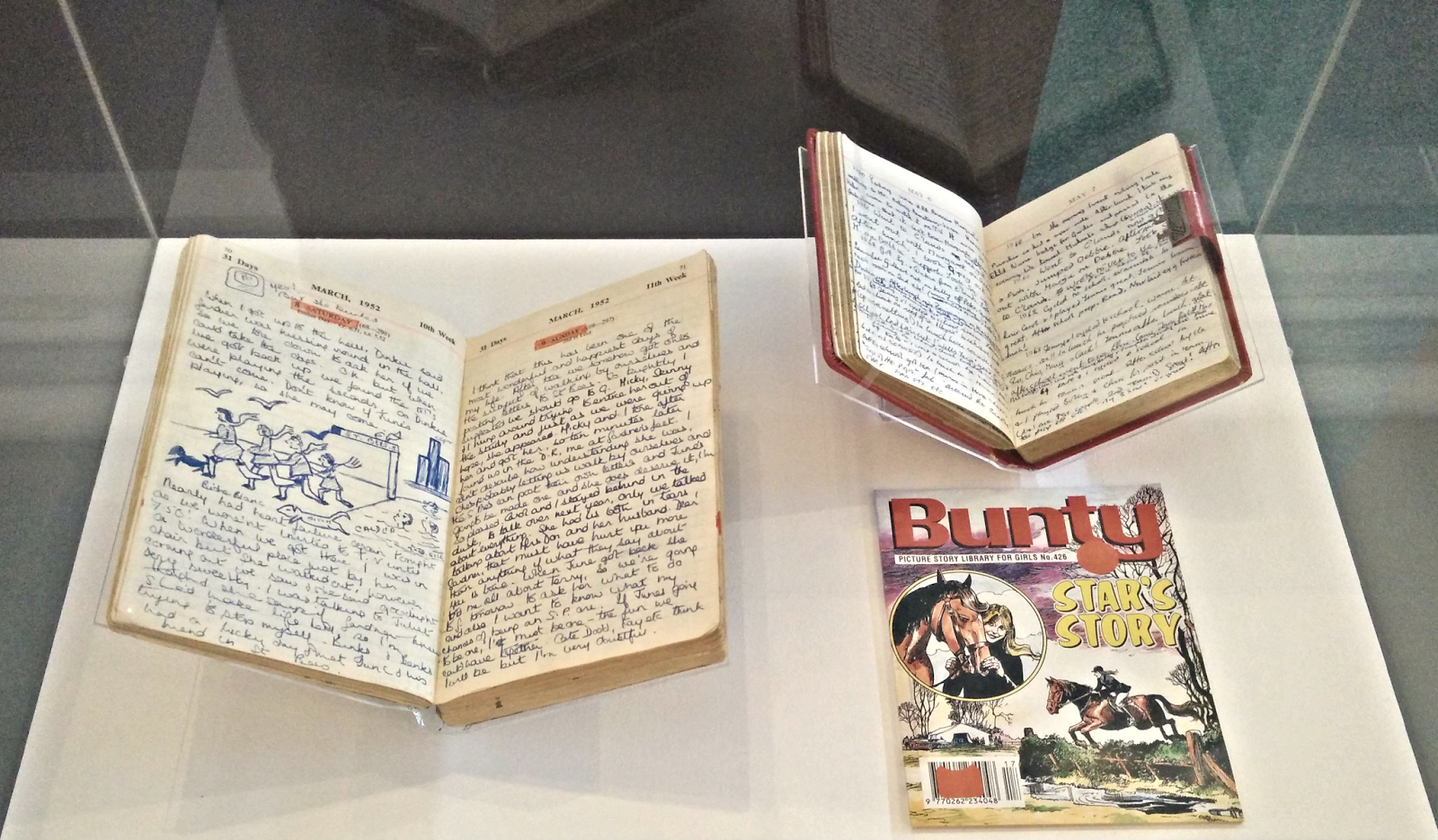

This summer the Museum of Childhood (MoC) hosted an exhibition on children and teenager’s diaries, with examples ranging from a 15-year-old teenage girl writing in 1947 about her turbulent love life, to a teenage colliery apprentice writing in 1838 about the death of a fellow miner. These diaries form part of a larger collection called ‘The Great Diary Project’ currently housed at the Bishopsgate Institute, incorporating both children’s and adults’ diaries from across the 19th and 20th centuries. According to The Great Diary Project website, the aim of the collection is to attempt to ‘rescue’ as many diaries as possible in order to preserve the highly personal accounts of everyday that they contain.

In this short piece I share some reflections on visiting this exhibition by linking together a number of themes I have been thinking through this past year. In particular, the (historical) materiality of children’s media practices, and issues around audience, privacy and authorship.

Getting up close and personal

Viewing the diaries arranged in glass cases, it’s hard not to be st ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.

ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.

In a recent article, Liz Moor and Emma Uprichard (2014) describe the significance of the materiality of archival objects. They propose we need to pay attention to, “how the material qualities of paper and type/script make the research process a sensory and emotive experience” (Moor and Uprichard, 2014: 6.1). By narrowly focusing on the ‘content’ of a diary or archival documents, they suggest we may miss “the sensuous ‘cues’ and ‘hints’ offered by the archive’s materiality” (2014: 1.2).

In an essay for the London R eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.

eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.

Individually, the diaries exhibited at the MoC offer a fleeting material and biographical trace of their authors, offering just a glimpse of the values, concerns, and aspirations that they chose to inscribe on paper at a particular moment. What remains is a material artefact, now spatially and historically separated from its author, yet still retaining the affective traces of the cares and concerns that they chose to impart on its pages.

“Who else but me is ever going to read these letters?”

All too often we read past media through a contemporary lens, judging their modalities and affordances by our own relationships with digital and online media in the present. The diary, in particular, has been subject to modern comparisons with online blogging and video diaries – both of which have been described as present-day ‘confessional’ devices. Comparisons between these different forms of cultural practice are, however, highly problematic. Rather than simply seeing them as analogue/digital equivalents, each cultural practice needs to be seen as shaped through a distinct set of values and technological modalities. I briefly focus here on the significance of privacy and audiences for the diarists.

In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.

In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.

A point of commonality across the diaries on display at the MoC was their often highly personal disclosure of thoughts and events significant to the writers’ lives. Looking through them I often felt an uneasy sense of prying, despite the often substantial ‘historical distance’. Occasionally the diaries were written in a way that appeared mindful of potentially uninvited and unwanted audiences. For example, one of the diaries was transcribed in an elaborate code devised by the author as a way of deterring would-be snoopers, whilst another diarist’s reference to ‘getting rabbit food’ was potentially used to hide a smoking habit. In these instances privacy might be seen as a highly localised encounter, with information specifically concealed from inquisitive friends, parents or siblings.

Our contemporary standpoint on privacy positions all forms of content production as potentially highly ‘risky’, even when not intended for wider audiences. During the recent spate of celebrity photo leaks the EU digital commissioner Günther Oettinger placed part of the blame on the victims for having been ‘stupid enough’ to create the images. Our contemporary networked world is one in which privacy is positioned as primarily the responsibility of the individual, and where personal content can rapidly circulate through wider audiences without warning or consent. Consequently, contemporary teenagers are increasingly burdened with the fear of spoiling reputations through the content they produce. This is not to say that the diarists displayed at the MoC did not have their own sets of concerns around privacy and audience, but it is nonetheless important to acknowledge the fundamental differences in the way that such concerns are actualised and played out.

Further Reading

Ford, M. (2014). ‘Pomenvylopes’, The London Review of Books, 36(12), pp. 23-28.

Franks, A. ([1952] 2011). The Diary of a Young Girl. London: Penguin.

Moor, L. & Uprichard, E. (2014). ‘The Materiality of Method: The Case of the Mass Observation Archive’, Sociological Research Online, 19(3), 10.

Penlington, N. (2014). The Boy in the Book. London: Headline.

Liam Berriman November 19th, 2014

Posted In: Blog

Tags: archive, curation, diaries, everyday, Liam Berriman, materiality, museum of childhood

ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.

ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.  eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.

eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.  In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.

In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.