Liam Berriman, Lecturer in Digital Humanities/Social Science

Over the last couple of months I’ve been involved in the development of a project with colleagues at the Sussex Humanities Lab that will look at how we conduct participatory research with children and young people using digital devices. As part of the project we will explore new ways of using different computational methods to ‘hack’ digital devices in order to make participation in research more accessible to different groups of young people. One aspect of this study will look at how we might experiment with the affordances of digital devices as ‘research tools’ in order to re-configure how they are used and the kinds of data they generate.

During the last decade, digital devices have become popular research tools for participatory and ethnographic research with young people. A great deal of participatory youth research now involves researchers and/or participants taking photographs or recording sounds using readily available digital devices, such as mobile phones. Whilst these digital devices have been used to produce a lot of fascinating research on young people’s lives, they often leave open a number of unanswered methodological and ethical questions around the mediatory role of digital devices in research. Here, I want to briefly reflect on three important ways that we need to re-think the role of digital devices in participatory research with young people:

1. Digital devices as ‘black boxes’ – A key challenge of digital devices in research are the way they ‘black box’ the processes of data collection, storage and circulation. Bruno Latour has described how ‘black boxing’ occurs “whenever a piece of machinery or set of commands is too complex” and we (as users) “need to know nothing but its inputs and ouputs” (2000: 681). For the most part, our understanding of how digital devices work, and what they are capable of, is mediated by simplified visual interfaces of menus and settings. Consequently much of the computational complexity of digital devices remains hidden from view, leaving large gaps in our knowledge as to precisely what data are collected (e.g. metadata such as GPS location), how that data is being stored (e.g. local memory or cloud services), and how that data is handled and circulated (e.g. via encrypted or unencrypted channels). These gaps in our knowledge pose significant issues for what role we allow digital devices to play in capturing data that may be ethically sensitive.

2. Digital devices as commercial products – Related to the first point, digital devices are commercially manufactured products that have not been designed for use as research tools. As researchers we ‘appropriate’ these devices, drawing on existing affordances of devices (e.g. portability, camera functionality) to facilitate specific research activities. In recent years there have been a number of innovative studies that have creatively appropriated digital devices into research – stretching and subverting their affordances. Nonetheless, the potential uses of these devices for research are by-and-large limited to the parameters set by their consumer-driven design. Consequently, the possibilities for what kinds of data can be generated are often pre-determined and closed down by their design specifications.

3. Digital devices as ‘democratising’ research? – The growing ubiquity and availability of digital devices in everyday life has paved the way for growing numbers of studies that invite participants to capture data about their lives (see for example Wendy Luttrell’s Children Framing Childhoods and Wilson & Milne’s Young People Creating Belonging). In the ‘Face 2 Face’ and ‘Curating Childhood’ studies, we invited young people to record a ‘day in their life’ using either their own digital devices or ones supplied by us. A lingering question from these studies was the extent to which such activities might be seen as ‘democratising’ research and enabling participants to share their lives on their own terms. In particular, the extent to which the parameters of research participation are foreclosed by a particular digital device. In part, this requires a more honest assessment of what forms of research participation digital devices both ‘open up’ and ‘close down’, and how this might vary for different groups of young people taking part in research (e.g. with physical disabilities).

Our study currently under development will explore new ways of ‘opening up’ digital devices within participatory youth research. In order to challenge digital devices as closed data ‘black boxes’, we will seek to explore new participatory research methodologies that involve young people ‘hacking’ research tools and specifying their affordances (such as sensory inputs) for themselves.

Liam Berriman April 23rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: digital data, digital devices, hacking, Liam Berriman, participatory research, Sussex Humanities Lab, youth research

Dr Liam Berriman, Lecturer in Digital Humanities/Social Science, University of Sussex

In 2007, Savage and Burrows predicted a ‘coming crises of empirical sociology’ as mainstream sociological methods were muscled out by new commercial data analytics techniques. Reflecting on their paper nearly a decade later, they admit that the scale of disruption caused by ‘big data’ (as it is now known) was unimaginable, even at that moment in time (Burrows & Savage 2014).

Our conceptualisation of ‘data’, and the language we use to describe it, have been irreversibly changed by the arrival of big data. For a new breed of data analysts, any dataset that is less than ‘total’ or ‘complete’ has become ‘small data’. The very language of data has been transformed by a new lexicon of analytics, real-time, tracking and scraping etc. However, remaining relatively unchanged is our language for talking about the ethics of ‘big data’.

This short piece focuses on one particular aspect of big data’s methodology – ‘data scraping’ – and the ethical questions it raises for researching young people’s lives through digital data.

According to Marres and Weltevrede (2013), scraping is an ‘automated’ method of capturing online data. It involves a piece of software being programmed (e.g. given instructions) to extract data from a particular source and creating a ‘big’ dataset that would be too onerous to capture manually.

Over the last few years, ‘scraping’ has been much lauded as a means by which data capture can be ‘scaled up’ to new analytical heights, particularly in relation to one of the most popular sources for big data capture – social media. Whilst ‘scraping’ techniques have advanced, a much slower trend has been the discussion of what ethical frameworks and language we need for robustly interrogating these techniques.

As one of the largest constituent users of social media, young people are a particularly relevant group within these debates. Data scraped from social media inevitably captures the conversations, thoughts and expressions of young people’s lives, even if as an ‘inadvertent’ by-product of research.

In 2010, Michael Zimmer reported on a study that had captured the profile data of a whole cohort of American college students on Facebook. The data had been taken without permission and a failure to appropriately anonymise the data had seen the identities of the students revealed. Zimmer’s article provided a robust critique of a growing data capture trend where all data not hidden by privacy settings was seen as consensually ‘public’, and available for analysis.

The ethical lessons learnt from incidents such as these have tended to focus more on greater care for data anonymization and security, and less on issues of consent and intrusion. Again, Zimmer (2010) has been particularly vocal in refuting claims that techniques such as anonymization through aggregation are ‘enough’[1].

How do these debates connect with young people’s social media data? Television programmes such as Teens and The Secret Life of Students[2] have played a significant role in perpetuating the idea that young people are less concerned than adults about having their data made public. However, studies have repeatedly shown that young people are highly concerned about privacy online (boyd, 2014; Berriman & Thomson, 2015), and the disclosure of their digital data (Bryce & Fraser, 2014).

A little while ago, I became aware that ‘scraping’ has a colloquial meaning in some UK secondary schools. According to Urban Dictionary (think Wikipedia for slang terms and phrases), the term ‘scrape’ is used to describe:

a person intruding on something. To say that one has come out of nowhere and intruded on a conversation.

[E.g.] ‘two people have a conversation’, ‘another person listens in’

one person out the original two people says “scrape out” to the other person.

This colloquial definition makes reference to ‘scraping’ as an unwelcome form of eavesdropping and intrusion on a private conversation. In the context of these ethical discussions, this definition seems particularly apt. It emphasises that privacy is a concern for young people, and that unsolicited ‘scraping’ of private conversations is ethically and morally contentious.

At present, there is a lack of serious ethical debate about the scraping of young people’s digital data. The presumption of public-as-consent doesn’t cut it. We need a new ethical language for talking about these issues, and young people’s voices need to be represented in these debates.

[1] Indeed, how ‘successful’ these techniques are remains debateable – see Ars Technica, 2009

[2] Two documentary series by production company Raw for Channel 4 that followed young people’s social media lives by harvesting their Tweets, texts, and Facebook updates.

Liam Berriman February 23rd, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Tags: automation, big data, crises, digital data, ethics, Liam Berriman, scraping

Dr Liam Berriman

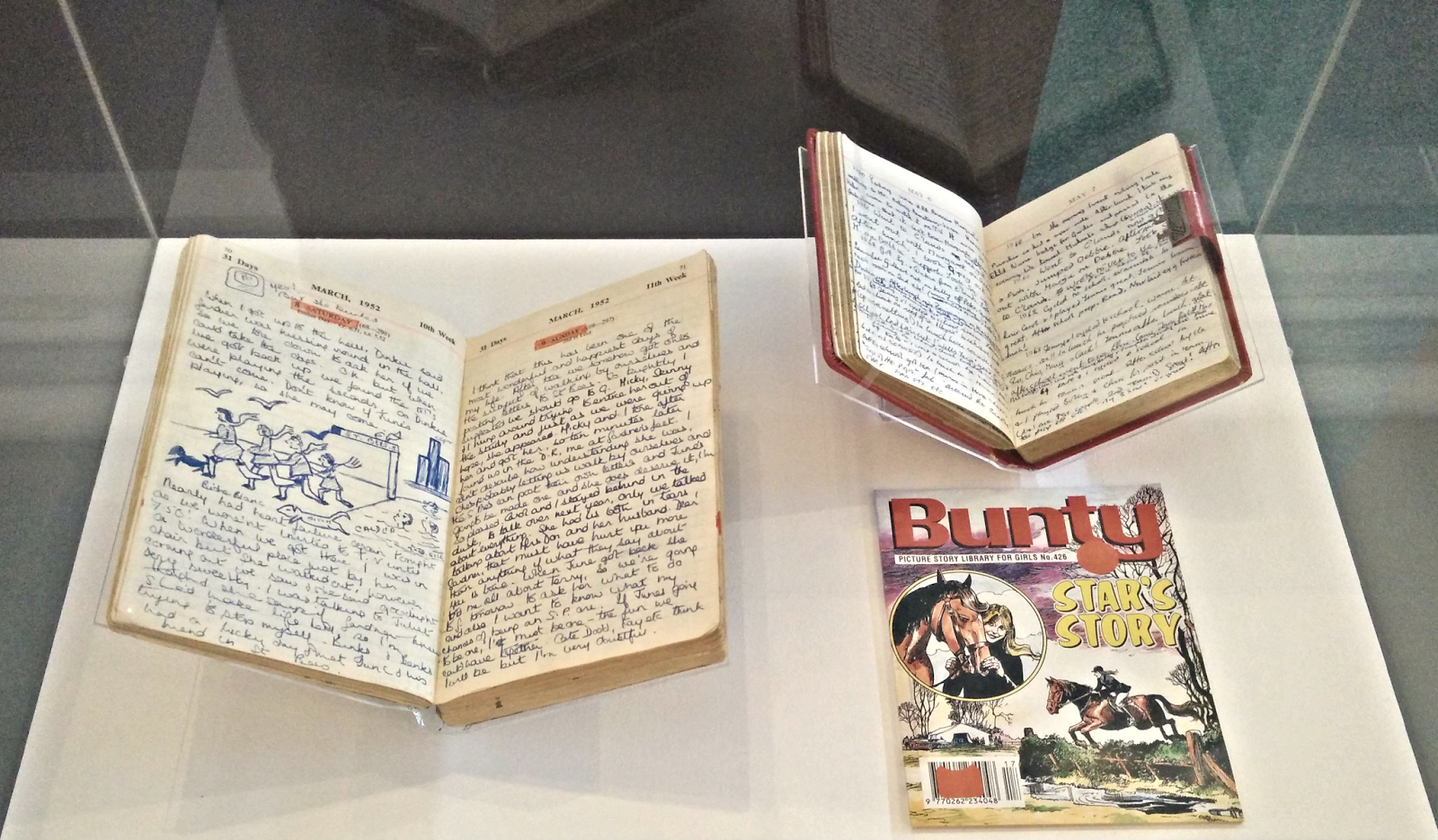

This summer the Museum of Childhood (MoC) hosted an exhibition on children and teenager’s diaries, with examples ranging from a 15-year-old teenage girl writing in 1947 about her turbulent love life, to a teenage colliery apprentice writing in 1838 about the death of a fellow miner. These diaries form part of a larger collection called ‘The Great Diary Project’ currently housed at the Bishopsgate Institute, incorporating both children’s and adults’ diaries from across the 19th and 20th centuries. According to The Great Diary Project website, the aim of the collection is to attempt to ‘rescue’ as many diaries as possible in order to preserve the highly personal accounts of everyday that they contain.

In this short piece I share some reflections on visiting this exhibition by linking together a number of themes I have been thinking through this past year. In particular, the (historical) materiality of children’s media practices, and issues around audience, privacy and authorship.

Viewing the diaries arranged in glass cases, it’s hard not to be st ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.

ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.

In a recent article, Liz Moor and Emma Uprichard (2014) describe the significance of the materiality of archival objects. They propose we need to pay attention to, “how the material qualities of paper and type/script make the research process a sensory and emotive experience” (Moor and Uprichard, 2014: 6.1). By narrowly focusing on the ‘content’ of a diary or archival documents, they suggest we may miss “the sensuous ‘cues’ and ‘hints’ offered by the archive’s materiality” (2014: 1.2).

In an essay for the London R eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.

eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.

Individually, the diaries exhibited at the MoC offer a fleeting material and biographical trace of their authors, offering just a glimpse of the values, concerns, and aspirations that they chose to inscribe on paper at a particular moment. What remains is a material artefact, now spatially and historically separated from its author, yet still retaining the affective traces of the cares and concerns that they chose to impart on its pages.

All too often we read past media through a contemporary lens, judging their modalities and affordances by our own relationships with digital and online media in the present. The diary, in particular, has been subject to modern comparisons with online blogging and video diaries – both of which have been described as present-day ‘confessional’ devices. Comparisons between these different forms of cultural practice are, however, highly problematic. Rather than simply seeing them as analogue/digital equivalents, each cultural practice needs to be seen as shaped through a distinct set of values and technological modalities. I briefly focus here on the significance of privacy and audiences for the diarists.

In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.

In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.

A point of commonality across the diaries on display at the MoC was their often highly personal disclosure of thoughts and events significant to the writers’ lives. Looking through them I often felt an uneasy sense of prying, despite the often substantial ‘historical distance’. Occasionally the diaries were written in a way that appeared mindful of potentially uninvited and unwanted audiences. For example, one of the diaries was transcribed in an elaborate code devised by the author as a way of deterring would-be snoopers, whilst another diarist’s reference to ‘getting rabbit food’ was potentially used to hide a smoking habit. In these instances privacy might be seen as a highly localised encounter, with information specifically concealed from inquisitive friends, parents or siblings.

Our contemporary standpoint on privacy positions all forms of content production as potentially highly ‘risky’, even when not intended for wider audiences. During the recent spate of celebrity photo leaks the EU digital commissioner Günther Oettinger placed part of the blame on the victims for having been ‘stupid enough’ to create the images. Our contemporary networked world is one in which privacy is positioned as primarily the responsibility of the individual, and where personal content can rapidly circulate through wider audiences without warning or consent. Consequently, contemporary teenagers are increasingly burdened with the fear of spoiling reputations through the content they produce. This is not to say that the diarists displayed at the MoC did not have their own sets of concerns around privacy and audience, but it is nonetheless important to acknowledge the fundamental differences in the way that such concerns are actualised and played out.

Further Reading

Ford, M. (2014). ‘Pomenvylopes’, The London Review of Books, 36(12), pp. 23-28.

Franks, A. ([1952] 2011). The Diary of a Young Girl. London: Penguin.

Moor, L. & Uprichard, E. (2014). ‘The Materiality of Method: The Case of the Mass Observation Archive’, Sociological Research Online, 19(3), 10.

Penlington, N. (2014). The Boy in the Book. London: Headline.

Liam Berriman November 19th, 2014

Posted In: Blog

Tags: archive, curation, diaries, everyday, Liam Berriman, materiality, museum of childhood