by Beth Collard and Danny Millum

Before we start – a confession. This title and thesis (such as it is!) of this month’s post has been almost completely plagiarised from The Dig podcast episode ‘The Rise of OPEC’. In it Giuliano Garavini talks about how while the oil consuming nations of the Global North saw the surprise imposition of an oil embargo following by oil price rises in terms of crisis, this could not have been the case for those countries imposing the embargo – you can’t be surprised by your own actions. He believes that it is better instead when seeing these events from the perspective of producer countries to talk of a revolution – the effects of which are still being felt today.

This made us think – can we use our library collections and digital resources to try and do the same thing? We’ve therefore split this post into two parts – in the second part Beth takes a deep dive into our online digital newspaper holdings to see what the British media made of the crisis during the last 3 months of 1973.

First, though, Danny re-enters the BLDS Legacy Collection basement to explore Global South takes on the revolution. Spoiler alert – it also turned out to be kind of a crisis there as well…

[Quick and recurring disclaimer – as ever our aim with these blogs is to promote our collections and illustrate how they might be used for further research. We’re not experts on 1970s geo-politics and this is merely a tiny cross-section of the available materials. If you think you can do better – great, that’s what we want to hear! Get in touch via library.collections@sussex.ac.uk and we can arrange access to these and many more materials].

The first thing we discovered was that to find these takes we couldn’t just rely on searching the collection by title or keyword – there simply aren’t that many government publications directly or solely addressing October 1973 and its repercussions. Instead, we needed to look for journals or reports which were concerned with oil and energy more generally, and search within these for relevant references. We also searched a broad spread of dates, reasoning that the impact and meaning of 1973 would be still be being contested throughout the remainder of the decade (and beyond, but you have to stop somewhere!).

Understandably, the responses we found through this method differed between oil-producing and oil-consuming countries.

So in the pages of Bangladesh’s Oilnews we find an article entitled ‘A Parallel Fuel’:

‘The impact of “Energy Crisis” first felt after the “Oil Embargo” by OPEC in 1973 and followed later by a series of crude oil price increases, has acted specially hard on the overall economy of countries like Bangladesh whose Energy bills are now topping the list of major “foreign exchange consumers”. One of the “Short-term” Energy solutions for Bangladesh should therefore include saving and supplementing the present fuel/energy systems. The introduction of the use of Liquified Petroleum Gas represents such a supplementary fuel system…’ (Oilnews, November/December 1979, p. 8)

For Bangladesh then, 1973 IS a ‘crisis’ and at least one of the consequences has been a search for diversification through LPG.

Discourses of uncertainty and crisis are also found in the pages of An Oil Refinery on Lamma Island? from the Hong Kong government, which states starkly the environmental trade offs the new situation has produced:

‘The community if it wishes to reject the scheme in order to preserve the amenity value of N. Lamma in its unspoiled state, should be prepared to face the consequences of having reduced control over securing its energy supply and reserves in a world where fears of an impending world shortage are already being strongly voiced.’ (An Oil Refinery on Lamma Island?, 1973, p. 7)

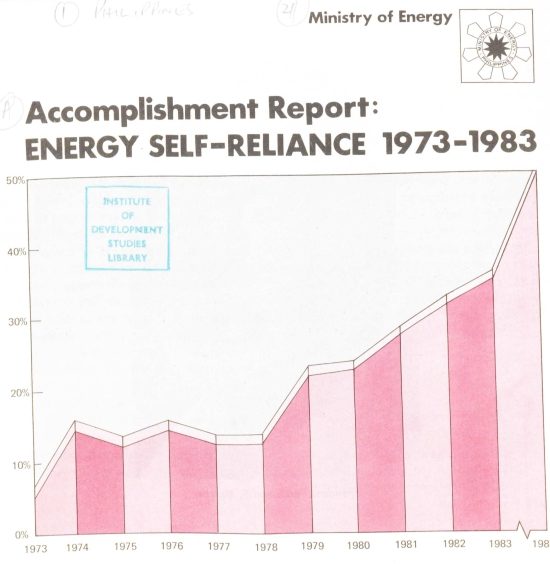

A similar post-1973 drive to increased self-reliance for oil importing developing nations can be found in the pages of the following Philippines Ministry of Energy’s publication:

‘Cited as a model for oil-importing Third World countries, the Philippine energy program has reduced imported oil dependence from a high of 92% in 1973 to only 65% by 1983 … [through] sensible and pragmatic policies to guide its own and private sector activities.’ (Accomplishment Report: Energy Self-Reliance 1973-1983, 1983, p. 3)

Note the reference to the private sector – a clear sign that we are now well into the 1980s!

A very different take can be found in Oil Politics and India, a Communist Party of India pamphlet from 1975. This gets closer to the dichotomy presented by our podcast, with the ‘revolutionary’ argument that these developments:

‘may go a long way in drastically changing the economic landscape of the world and thereby giving a smashing blow to the international oil companies and their main mentor, US imperialism.’ (Oil Politics and India, 1975, p. 5)

The Indian Ministry of Petroleum was a little more sober in its analysis:

‘In view of the high level of petroleum prices and not too easy balance of payments position, it is clearly necessary to enlarge the domestic component of crude oil supplies as rapidly as possible’. Report of the Oil Prices Committee (1976, p. 12)

Another angle is found in a publication from the Indonesian government from 1972, before the crisis/revolution. Indonesia was a member of OPEC, but its line at this point appears to be a moderate one – while Indonesian involvement in the oil industry needs to grow, ‘we know it is beyond our ability to undertake the operations done by those foreign companies’ (Prospect of Oil for Our National Prosperity, 1972, p. 16).

Another pamphlet from 1972 from OPEC new-joiner Nigeria also considers the trade off between the need for foreign expertise and the political and economic sovereignty of the host nation:

‘In terms of social and political stability it cannot be right to allow foreign companies to control 65 per cent of the country’s earnings of foreign exchange or even more’. (Nigerians and their Oil Industry, 1972, p. 20)

[It is worth noting that these legal arguments over the rights of capital versus the rights of countries continue to this day – and presumably interesting for those studying the history of this contested terrain to read government publications of this sort from the early 1970s, which bear the flavour if not the overt imprimatur of the New International Economic Order].

Post 1973, we get from Nigeria the first evidence that a crisis for one country is an opportunity for another:

‘By 1973 the Middle East Crisis which itself produced a crisis in international oil politics and economics, affected Nigeria in a peculiar though welcome manner – Nigeria being fortunate to be one of the oil producing countries. The increase in the price of crude oil produced an unprecedented up-surge in the economy of the country’. (Report of the Judicial Commission of Inquiry into the Shortage of Petroleum Products, 11th November, 1975, p. 7)

Libya was another OPEC member, but under a very different type of government. A fascinating pamphlet disseminated by the Press Department of the Libyan Embassy in London states that over the last half decade ‘the Government of Libya has taken on the oil giants, and has forced them to accept its terms, at the same time showing the way to the other major oil producers associated in the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries, OPEC’. Libyan Oil: Two Decades of Challenge and Change, 1978, p. 5

Finally and super-quickly – two quotes from Sudanese publications.

‘I have noticed from my experience with developing countries benefiting from “Kuwait Fund for Arab World Development”; the need is not merely for administering loans and funds to share in the development of the recipient countries … [but also for] the transfer of technology as essential tool and prerequisites for economic development’ (Panel on Horizontal Transfer of Technology as a Tool for Development, 1974, p. 19)

Here again, we have the NIEO sense of solidarity between primary producing countries both oil and non-oil. But that was 1974. By 1985 you would have expected (as with the Philippines) the World Bank and private sector to be getting involved. But the National Energy Plan 1985-2000 takes a different approach, a fascinating document that illustrates the value of the BLDS Legacy Collection in helping us compare and contrast different country responses to the same global developments. The Sudanese propose a governmental plan involving renewables, prioritised consumption, technology and planning, concluding:

‘With a vigorous, well-directed effort at change Sudan can improve the energy future by providing enough supply at an affordable cost to meet the demands of the economy. Let this National Energy Plan serve as the commitment of the Nation and the Government to turn that idea into action’ (The National Energy Plan 1985-2000, 1985, p. 119).

It all sounds great – but as the government was overthrown three months into its 15 year plan this must just remain another BLDS Legacy might-have-been document….

********************************

Now, as promised, for the second part of the post Beth will take a look at relevant holdings in the library’s online collections.

The library’s collection of online resources features access to several databases of historic newspapers, which offers fascinating insights into historical moments in time from a contemporary perspective. My approach to finding relevant articles from the time relating to reporting on the energy crisis was to focus upon a specific timeframe to narrow down what would otherwise be an unmanageable amount of information. To mark the 50th anniversary of this oil crisis hitting the UK and much of the Western world, I focused on a date range between roughly the beginning of October 1973 and the end of December 1973, although broader searches that take into account the rest of the decade would certainly be achievable for a larger scale project.

Each historic newspaper collection is separate, so I took each database individually and compiled my findings on a spreadsheet, creatively starting with the Daily Mail Historical as it was the top of the alphabetised list. Using the advanced search feature, I narrowed down my search to my desired date range, then further narrowed it by indicating the terms “energy” or “oil” should be present somewhere in the keyword field to account for articles with titles that may not directly reference these words but whose main text does. I then initially chose to exclude documents which had been tagged as either “advertisements” or “sports news”, as they made up significant numbers of the results and were mostly unrelated to the energy crisis (bar a few exceptions which I will return to later). More refined searches with alternative keywords would of course yield more specific results and weed out the amount of irrelevant articles that happened to meet the search terms, but for a cursory exploration of newspapers in this period I found these terms up to task.

It was then a matter or browsing the results (which numbered in the thousands) to pick out articles that examined the unfolding energy crisis in an interesting way, making note of any that stood out for future reference and comparison. For further searches of other historic newspaper databases, I repeated the same general search but also searched with more specific dates when I had noted a specific event had been reported on in a previous newspaper in the hopes of finding parallel articles that discussed the same event for a more direct comparison of reporting. For this exploration, I focused on 5 national newspapers: the Daily Mail, Economist, Guardian/Observer, Times, and Financial Times, and each database provided a wealth of information from political reporting, economic analysis, opinion pieces, and practical guidance for readers.

Reading through my results gave an interesting picture on the crisis from different sources reporting on the same events, and while obviously the content of the articles is very telling about a given newspapers demographic and politics, I found what was not reported on was often just as telling as what made it to the pages. The Daily Mail, for instance, gave comparatively little attention to the crisis beyond the UK (in the rest of Europe or Global South, for instance) unless it had some direct, tangible effect on the UK. The Daily Mail also featured a large amount of opinion pieces on the crisis and, perhaps unsurprisingly, heavy use of emotive, sensationalist language in the headlines and articles that often blurred the lines between factual reporting and opinion columns and was not always easy to spot at a glance.

The Mail focused heavily upon the effect of the energy crisis upon UK citizens daily lives, and had the lion’s share of articles on blackouts, petrol rationing, and the imposed three day week between all the newspapers. It turned to sensationalising and catastrophising the crisis far sooner than the Guardian and the Times, with articles as early as mid-October employing doom and gloom thinking towards rationing and imposition on daily life. A clear example of this is seen in the headlines alone on the 19th October 1973 when the British government had suggested that, should a voluntary reduction in use of petrol not be effective, rationing may be considered by the end of the year. The Guardian’s headline for this announcement was straightforward: “Oil rationing may come by Christmas”, while the Daily Mail opted for the far more provocative “Why you may be allowed to drive only 50 miles a week by Christmas.” This is a recurring theme with the Mail, with each new development detailing the effect it will have on “you”, the reader: Christmas holiday flights ruined, blackouts in your home scuppering TV schedules, your driving plans thwarted by petrol rationing. At times, the Mail draws on the memory of Blitz spirit and rationing in the Second World War to call for unity and argue that the UK has survived worse crises through fraternity (such as with articles from December 1973 titled “Battle of the Blackout” and “A Time to Stand Together”). At others it seems to seek to provoke anger and disharmony by amplifying stories of selfishness and greed (an letter to the editor titled “Why should I save petrol?”, or a December article titled “They’ll try anything to get petrol! I’m a surgeon, said Mr Scruffy…I’m a father-to-be, lied bachelor”). Perhaps the cynical takeaway from this is that some things never change.

Comparatively, the Economist and the Financial Times took similar approaches to one another, focusing more on economic and political analysis from both a domestic and international perspective. The Economist also features opinion pieces like the Daily Mail, but are provocative in a less extreme way (such as a December 1973 article debating the pros, cons, and possible reactions to the introduction of petrol rationing titled “Would Britain love rationing?”). The Financial Times, again perhaps predictably, is a drier affair and focuses its analysis of the unfolding crisis on the politics of oil embargos and the impact they have on commerce and industry on a national and international scale.

Bridging the gap between the Daily Mail and the Economist/Financial Times are the Times and the Guardian/Observer, which both feature a mixture of higher-brow reporting on the facts of the crisis from a political and economic standpoint, as well as opinion pieces on what this means for the UK population on a practical level. Out of all the newspapers in this brief study, the Times goes into the most detail on the nitty gritty of the blackouts, restrictions, and changes to working and home life that could be expected over the coming months. It was the only newspaper, for instance, to have specific articles detailing the exemption of schools and religious venues from heating bans (“Schools not included in ban on heating”, 16/11/1973, and “Places of worship and religious education exempted from ban on electric heating”, 24/11/1973). One interesting article featured by the Times is a breakdown of the ongoing peace talks in the Middle East and how these could affect the situation in the UK titled “A plain man’s guide to the Middle East Peace Talks” (21/12/1973) which is a fairly neutral and simple breakdown of the context and objectives of the peace talks and its participants.

The Guardian/Observer archive is broadly similar in focus with a different political slant, the key difference being the Guardian is the sole paper to make frequent reference to the impact the energy crisis may have upon the Global South (for better or worse), such as an article pointing out how Nigeria’s own oil reserves are bolstering their international recognition in light of the embargo (“Nigeria key factor in oil equation” 16/12/1973). The Observer also contains the article that stuck out to me the most for its prescience and surprising relevance to various crises and global developments occurring today, titled “Living with the Apocalypse” (23/12/1973). The article takes a step back from the energy crisis to analyse what it means about the state of the world as a “global commune”, and how current rates of economic and industrial growth with a focus on individual and national wealth and interests alone are simply no going to be viable for much longer as the world becomes increasingly interconnected and interdependent. As well as the unique perspective on the global community, it also focuses on how such crises only amplify wealth inequality at home and abroad, and dismisses what it sees as quick fixes to the problem that do not target the root causes, and also (unusually compared to the other newspapers) considers elements of the environmental equation behind this crisis and what this may mean for the future. This article in particular and the conclusions it draws about the energy crisis stood out to me not only for its unique take on the situation that considers angles not often explored in as much depth by others at the time, but also for being just as relevant now almost 50 years after it was originally written, showing the value this resource holds.

There’s obviously a huge amount more to explore here, but we hope that this brief survey has whetted your appetites. Sussex staff and students can access our online newspaper databases here, and anyone reading this should feel free to drop us a line at library.collections@sussex.ac.uk.

Leave a Reply