The Colonial Office and India Office Records both hold evidence of centuries of imperial administrative practice. Yet, in both their structure and content they differ considerably. Three months into our research, these differences are becoming ever more apparent. This month we will consider the composition of the archives with which we are working, and what this indicates about how the two offices approached colonial administration.

The Colonial Office in London, headed up by the Secretary of State for the Colonies, governed dozens of colonies across the globe. From New South Wales and Ceylon to Malta and Lower Canada, each of these colonies had its own Governor, legislative body, and network of local officials and judicial representatives. The demands placed upon each colonial government varied wildly, and as a result in many ways the Empire was quite disparate. It was the Colonial Office that was responsible for overseeing all these administrations, unifying them under the general umbrella known as the British Empire.

The Colonial Office operated quite differently from the India Office; the latter, as we will see, chiefly liaised with one central governing body in India that was, in turn, responsible for overseeing all the myriad regional administrations in South Asia. This distinction is reflected in Colonial Office Records, which are vast and virtually impenetrable in places. Exploring the papers of the Colonial Office certainly presents its own challenges. Papers are organised by colony, in volumes identified as “Despatches,” “Entry Books,” “Offices,” and “Individuals” (though the exact labels used varies from colony to colony). While for some colonies, despatches include comments from colonial office administrators and official replies, in other cases a hunt through the entry books and interdepartmental letters is needed in order to identify how the colonial office dealt with certain issues. In some instances, notes and official replies seem to have simply disappeared. As a result, following a single issue from beginning to end (even when related to only one colony) can entail looking through half a dozen different volumes. To construct a global perspective on any such issues – as we are attempting to do here – that process must be repeated for each of the Colonial Office’s multitude of dependencies.

A recent discovery related to the Cape Colony records for 1838 perfectly represents the experience of working with the Colonial Office Records. To preface, I should note that the indexes for that year are organised by the date they were received into the Colonial Office, while the correspondence itself is arranged by date written. While the correspondence is often helpfully stamped with the reception date, to find letters processed in the Colonial Office between January and March 1838 – as is the aim of our project at present – one must view volumes from 1837 and from the beginning of 1838. While this has been a relatively simple process for most of the colonies’ records viewed thus far, examination of the Cape Colony (for which there are 16 volumes of original correspondence just for 1837!) revealed surprisingly few letters from the months in question. I began by examining the most obvious volumes first, from September-December 1837, which for other colonies in that general geographic vicinity had been fruitful. However, the correspondence from these months was apparently only received in April. I then checked earlier despatches from 1837, but the latest of them was received in December. Only a handful of letters seemed to have been received from the Cape during the whole of January, February, and March. To ensure nothing had been overlooked, a full 20 volumes were studied. But nothing more was found. I then sought an explanation for this mysterious deficit through parallel examination of entry books and interdepartmental correspondence; even there so little was written during those months that it was impossible to draw any conclusions regarding the anomaly. However, it was apparent that something had caused communication from the Cape to be delayed, resulting in a disruption to administrative discussion of the colony in London. The cause can be ascertained only if we move our scope well beyond the Colonial Office first to Government House in Cape Town and then some 600 miles beyond that, to the eastern frontier of the colony: a political dispute over policy regarding the Xhosa chiefdoms in 1836-1837, which resulted in the dismissal of Governor D’Urban. His successor only arriving in April 1838, and D’Urban knowing he would be leaving, apparently held correspondence with the Colonial Office, resulting in a sudden flood of letters arriving in London in April, once he was gone.

This incident demonstrates the parallel examination approach required in order to extract meaning from the vast amount of information flowing in and out of the Colonial Office. Global issues – or even logistical concerns that primarily affect the Colonial Office – have been organised into volumes by colony, so this process must be repeated many times over to gain any sense of scope.

Not to complain, as the organisation of the records is likely indicative of the administrative approach employed by the Colonial Office. As a central administrative hub, the Colonial Office likely needed to examine related minutia from across the empire under their purview, even for management of regional concerns. For example, control of convict populations in New South Wales and Van Diemen’s Land required adjustments in sentencing procedures in other colonies such as Lower Canada and Barbados. Communication with other offices regarding seemingly unrelated, often-banal, subjects such as shipping costs and construction contracts, all would have contributed toward decisions made on this issue.

Consequently, even the process of working in the Colonial Office Records, and understanding why documents were organised as they were, will play a key role in understanding how this one office attempted to govern almost an entire global empire.

The records of the East India Company are very different from those of the Colonial Office: the cultures, modes and methods of Company rule in 1838, however complicated by a succession of central government interventions since the 1770s, remain distinct and idiosyncratic. Moreover, the centre of imperial power had to manage not a network of widely scattered colonies, but a single Indian Government in Calcutta. The history of the Company’s overseas centres of administration, in fact, is one of increasing centralisation, in which London progressively reduced the number of administrative nodes with which it had to communicate. A widely-dispersed network of factories in the early seventeenth century became a more organised archipelago of presidencies, in which one main factory would control several subsidiary ones: Java for the East Indies and South-East Asia, Calcutta for Bengal, Bombay and Madras for their respective portions of the subcontinent. By the early nineteenth century, the process of subordination had led to Bombay and Madras being ruled, more or less, by Calcutta.

At the same time, however, the centre of Company power in London had in a sense fractured: since the Regulating Act and East India Act of 1773 and 1774, ultimate sovereignty over India rested – de facto if not quite de jure – with the government rather than the Company, and the Company could do very little without consulting a Board of Control. So, while a simplified model of the Colonial Office’s informational network in 1838 might look like a single centre from which lines radiate, like spokes on a wheel, to various points on the periphery, that of Britain’s rule over India looks rather different: a double centre from which a single line of communication extends to the three major (with one pre-eminent) centres of government within India. Along this one vector of information, matters were divided to some extent by place and presidency. There were still separate despatches for Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, but correspondence was arranged mostly by subject. Between London and the Presidencies there was a constant traffic of packages of correspondence, including more or less all the business that could possibly be done in the work of governing a still-expanding territorial colony and a patchwork of native client states.

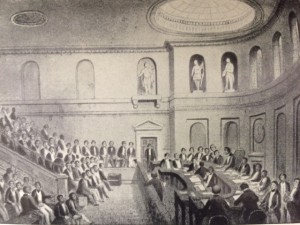

In seeing how this was done, and in trying to get the measure of how India was ruled in 1838, the Company Court Minutes are a good place to start. The Company had three distinct types of Court: rambunctious and quasi-parliamentary Public Courts, at which anyone holding a certain amount of stock could participate; discreet Directors’ Courts, featuring only the handful of directors who ran the company, and usually called only for the election of new members; and the Courts of Proprietors. These occurred at least once every week throughout the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and often more; most began at around eleven in the morning, and carried on until well after dinner time. General Courts were where policy was debated and ratified, appointments made, and correspondence cleared and sorted. (They were also, one imagines whilst reading the dryly pompous locutions of the minutes, events at which power was ritualised and a certain homosocial and mercantile ethic defined and performed.)

The Sale Room in the East India House, early nineteenth century, with a Public Court in progress. Repr. in William Foster, The East India House, its History and Associations (London: John Lane & Bodley Head, 1924).

The Court Minutes are, on first viewing, useful on three fronts: bureaucracy, the prioritization of communications infrastructure and governmental precedence, and the decentred locus of power.

Firstly, they provide a solid entry to a bureaucracy, its structures, rhythms and culture. The average Court meeting is a highly structured affair: correspondence is read out and sorted between three committees, dealing with Political & Military, Revenue and Judicial, and Financial and Home affairs. The court adjourns for a few hours while the committees confer, and on their return considers their replies, decisions, and draft paragraphs for inclusion in despatches. The drafts of correspondence, and the despatch paragraphs – the formalised briefings sent to India to direct action and policy – are either voted upon, or laid by for a week or two so that all members of the Company can see them; once voted on, they are sent off the Board of Control, which either approves them or suggests amendments. If there are amendments, these drafts can pass back and forth for weeks between Court and Board, with the Board always holding the power of veto.

Secondly, they provide an index, if only partial, of the concerns of governmental thinking at the time. In 1838, the topics that crop up every week are communication and sovereignty. The Directors and Proprietors are (understandably) obsessed with the speed and efficiency with which despatches pass between England and India: in trying to rule an enormous colony at a distance, they have to cope with a minimum time lag between a message sent out and a message received. Policy wrangles drag on for years; reports of proceedings in the native states in the first quarter of 1837 arrive in London in February 1838; accounts dating back five years or more pile up with every package received. The minutiae of communication, too, is of huge concern: in early 1838 the first Atlantic crossing by steam has just occurred, and the Company is dealing with the technical and logistical challenges of a technology which promises faster and more reliable communication. Coal depots are set up along the Cape and Suez routes, and there are endless enquiries about just how much coal is needed, whether the buildings can be sourced or built, and whether other countries’ ships should be allowed access to coal (sometimes yes, sometimes no). The Company’s agent in Alexandria is kept busy negotiating coaling in Mediterrannean and Red Sea ports, arranging the protection of armed Janissaries for despatches’ travel over the isthmus between the two seas, and sourcing parts and expertise for the repair of a steamship with a broken screw. The Court fields interminable letters from coal merchants tendering their ships for carrying coals from Llanelli to Bombay. The Courts themselves are responsive to the demands of communication: snap Courts are called when packets of letters arrive via Alexandria, the Cape, or Marseilles; each Court begins with a lengthy reading of all correspondence received, irrespective of subject or importance.

The other obsession is governmental precedence, and the vexed question of where authority actually lies. The tension between the Court and the Board is palpable in the Court Minutes. The formula “subject to approval of the India Board” is attached to even the most minor resolutions and drafts of letters. The weeks-long exchanges between the Board and the Court over policy differences, expressed sometimes in the most exacting disputes over the wording of despatches, cause endless frustration. Moreover, they’re often about subjects in which it is sovereignty specifically which is at stake: the power of the Board to appoint professors to the East India College at Haileybury, the structure of oversight of judicial appointees in Indian courts, or the power to grant pensions or pecuniary relief to impoverished ex-servants of the Company.

Thirdly, they show how difficult it is to pin down the sources of authority, and the ways in which government is always seemingly happening elsewhere.

The Court Minutes can give an impression of comprehensiveness and reach, of a gathering of men that – however frustrated by bureaucratic demands, procedure, volume, tedium, distance and politics – controlled an empire and its destiny. And this just isn’t true. The Directors did the work of policy-making, but ultimate sovereignty resided, if anywhere, with the Board; the business of governing India, within the policy and budgetary strictures the Court and Board hammered out between them, was done by the Government of India and its presidencies. The Board returns the Court’s drafts mutilated, but their deliberations clearly occur in a completely separate bureaucratic world; the attention to the minutiae of coal depots, and the debates over whether the Mediterranean packet should sail once a calendar month or once every four weeks, betray a continuing communicational powerlessness in the face of time, distance, international politics and the weather which won’t be significantly ameliorated until the telegraph becomes a viable medium; and the minutes are packed with Chelsea Pensioners’ requests for prize money from the Deccan wars, but millions of Indian subjects of Company rule are apparently completely silent. In these respects, these documents – produced by a body which liked to imagine itself as the very centre of British-Indian power – memorialise a surprising powerlessness.

Very interesting post (and project)!

I would add one caveat about the Colonial Office correspondence with the colonies: After 1931 it is no longer sorted into volumes of despatches, individuals, offices, etc., but in some kind of topical organization. I have not been able to figure out how to know which volume a specific document might be filed in, so that it seems one would have to order the dozens of volumes for a given year for a given colony and search through them all. If anyone has any ideas or experience with this, I’d love to know!

Fascinating blog and project. Has some similarities with the project I am involved with in New Zealand, of which my PhD forms part. We too are interested in different forms of authority articulated and exercised in metropole and colony and the way new ideas were adopted and modified by indigenous polities within New Zealand: see http://nzhistorian.com/2016/03/15/my-phd-has-begun/.

Have ‘followed’ your blog. Regards, S D Carpenter