In the early stages of World War I, the Raj came to the south coast of England in the form of over 4,000 wounded Indian soldiers. They convalesced in a number of specially constructed hospitals, including in the Brighton Pavilion. Between 1914 and 1916 the former Prince Regent’s Oriental-style palace became charged with the hubris and anxiety of the largest and most diverse Empire the world had ever seen. [1]

A Palace Becomes a Hospital

In August 1914, the Indian Army was roughly the same size as the regular British Army (around 240,000 men), but their deployment against the German Army was a thorny issue. British commanders had used Indian troops against a variety of opponents to conquer parts of South Asia, the Middle East and Africa, but the maintenance of ‘white prestige’, so necessary to the retention of those territories had deterred any use against white enemies. They had been held back from deployment against the Boers, for instance, in the South African War (1899-1902). Aside from the obvious military need though, for reasons that we will come onto, the Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, was keen to appease Indian opinion at this critical juncture. Although he intended to ‘keep the white race pure’, he decided that the loyalty of the Princely States in particular should be secured by trusting their soldiers to serve in the trenches alongside British counterparts.

Indian troops began arriving in Marseille from late September 1914 and by the time they were removed from the western front the following year, about 90,000 had seen active service as frontline troops and a further 50,000 as auxiliary labourers. The wounded were cared for initially in Marseille, but as the numbers increased the French Army suggested that with resources for white soldiers stretched, colonial subjects should be treated in England or Algeria. With some reluctance, the War Office opted for the former, and from November 1914 injured Indian men started crossing the Channel.

Lord Kitchener, the Secretary of State for War, appointed Walter Lawrence as Commissioner for Sick and Wounded Indian Soldiers in France and England. For the last five years, Lawrence had worked as Lord Curzon’s private secretary in the India Office. From November 1914, despite the lack of any military experience, he was responsible for every aspect of the wounded Indians’ treatment in England.

Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

With the facilities initially provided at Brockenhurst in the New Forest and Netley, Southampton, proving inadequate, Lawrence was relieved when the Mayor of Brighton, John Otter, offered the use of his town. Lawrence felt that Otter’s initial offer of the pier and racecourse were unsuitable, largely because they lacked any roof. He was delighted, though, when Brighton Corporation offered him the use of the Royal Pavilion.

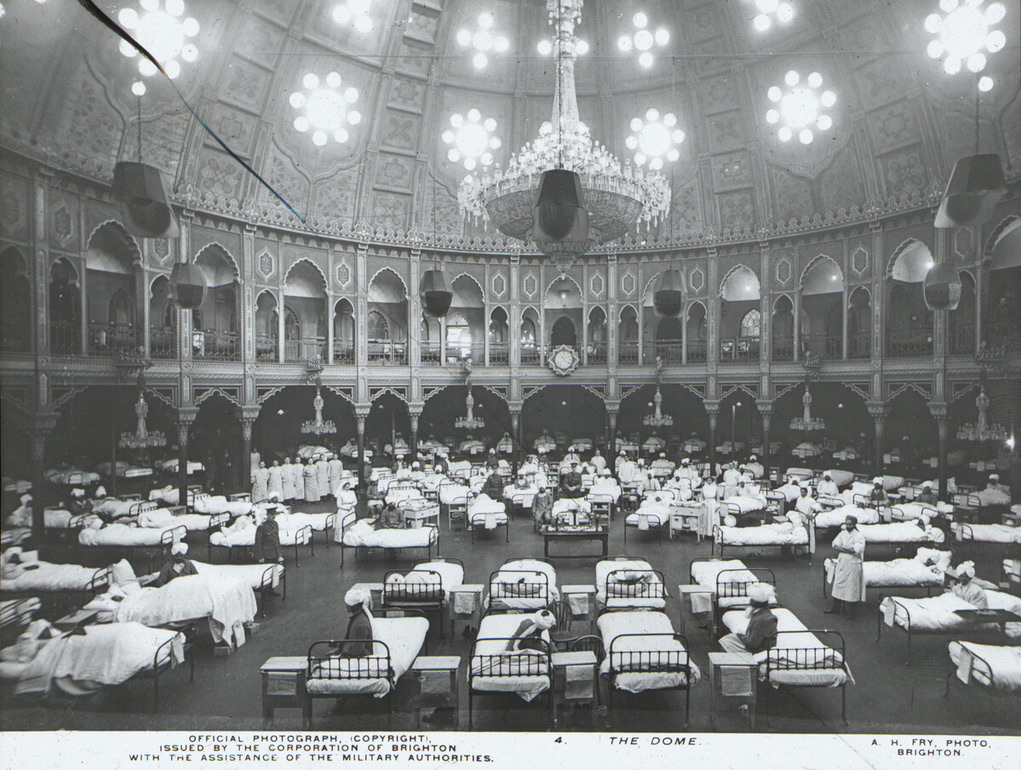

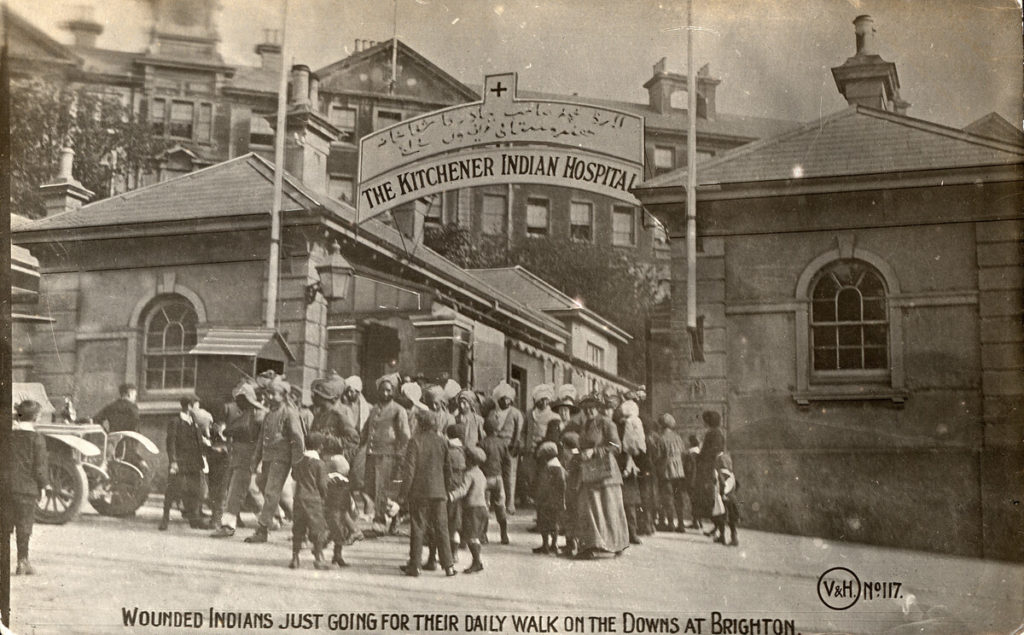

No building, Lawrence considered, could be more suitable as a place of convalescence for Indian men. Its oriental style would make them feel at home while they could relax in the seclusion of its ‘charming gardens’. The Pavilion Hospital would consist of the palace itself and the Brighton Dome and Corn Exchange, which lay in the same complex, hosting 724 beds. With the Corporation’s help, Lawrence was also able to procure a school that came to be known as the York Place Hospital, containing 600 beds, and the Brighton Poor Law Institution, renamed the ‘Kitchener Hospital’, with a further 2000 beds. He oversaw the conversion of each building, the setting of hospital wards amidst the Pavilion’s orientalist splendour especially attracting official photographers.

What a Welcome!

Between 1914 and 1916, Lawrence oversaw the treatment of 4,306 patients in Brighton. He preferred to recruit retired Indian Medical Service officers to treat them, filling the other medical positions with members of the Indian Volunteer Ambulance Corps, Indian doctors and volunteer medical students who were training in Britain when the war broke out. As well as serving as dressers and orderlies, the students acted as translators between British staff and Indian patients. Most of the cooks, cleaners and launderers were Indian men too, some of whom had been residing in England, and others hired from India.

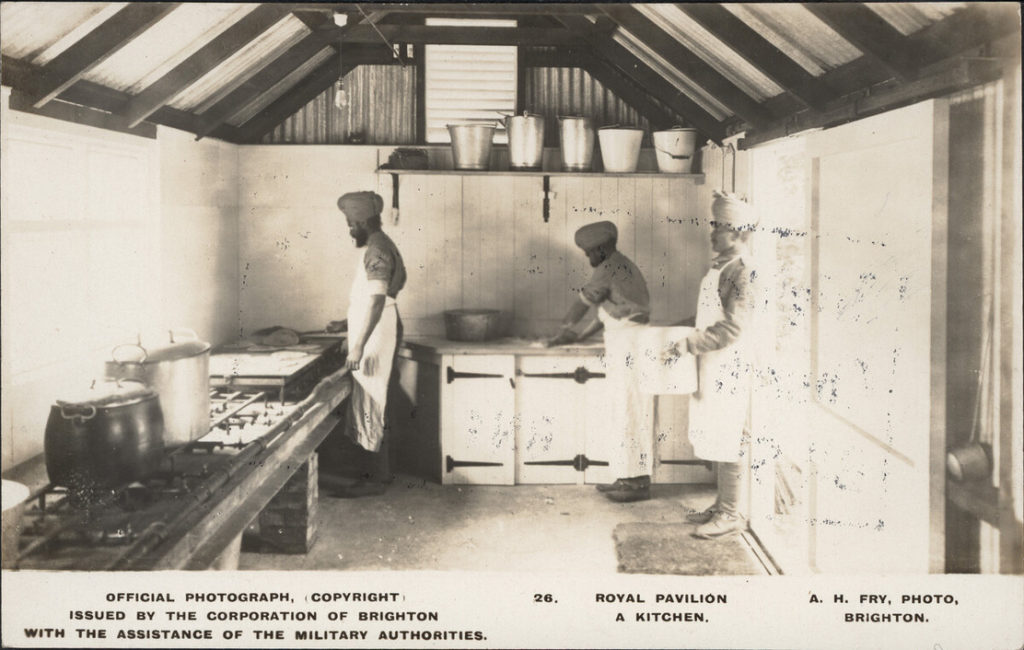

Lawrence made provision for religiously segregated wards, baths, toilet facilities, laundry services and water supplies. The kitchens were divided into separate sections to cater for Muslims, Hindus and vegetarians and men of the same caste handled, cooked and served the patients’ food. No beef or pork products entered the hospitals and special arrangements were made for slaughter and storing of meat.

Indian Soldiers at a butcher house. Featured on page 9 of the ‘Brighton, Hove and South Sussex Graphic 1914 – 1915’, 29 July 1915, Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove

Major James of the Kitchener Hospital, explained in a lecture on ‘Indian Sanitation’ in the Brighton Art Gallery, that ‘There were eight different kinds of diet and separate cookhouses for six different classes’. (He went on to regale his audience with ‘amusing’ tales of the Indian soldiers’ confrontation with European modernity, talking of soldiers who knew how to turn on a water tap, but ‘did not seem to see the necessity of turning it off’ flooding the bathrooms, and of patients nearly gassing themselves when they blew out the gas lamps instead of turning them off’.)

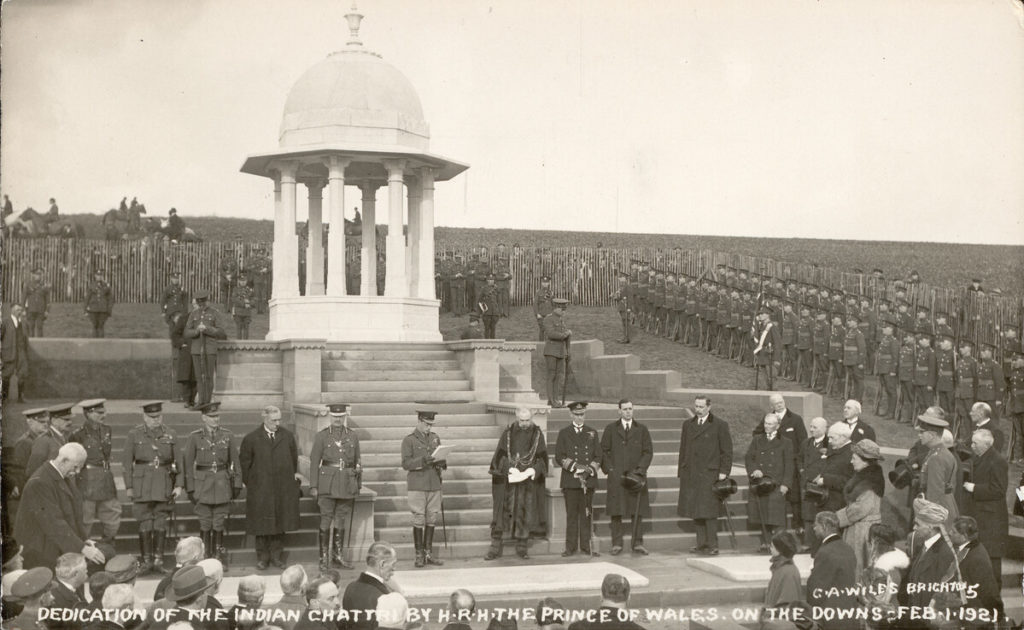

Presciently, Lawrence insisted that the arrangements for deceased soldiers were of particular ‘political importance’. Each hospital provided separate storage areas for the bodies and specific burial procedures according to religion, while the Home Office swiftly sanctioned cremation for Hindus and Sikhs at a site on the South Downs above Brighton. Fifty three cremations took place there on specially constructed ghats, and the location was marked with the unveiling of the Chattri memorial in 1921. The twenty one Muslim soldiers who died in Brighton were taken to Woking, where they were buried near the mosque with Muslim rites and a full military firing squad. As The Times, remarked, ‘The action of the civic authorities at Brighton in the matter is warmly appreciated in India, the Viceroy, Lord Chelmsford [Hardinge’s successor from April 1916], has written to the mayor thanking him’.

The Times also printed a letter from the Maharaja of Bikanir contrasting the solicitude shown by the British imperial authorities with what might have been expected of the Germans: ‘the military authorities have spared no pains or outlay to ensure adequate provision being made for the cremation or burial of soldiers in full accordance with the ritual and customs of their respective communities’.

Lawrence also made great efforts to ensure that patients could worship as they wished. Marquees and huts were erected within the grounds of each hospital, functioning as temporary Mosques and Gurdwaras. The Indian Soldier Fund provided appropriate religious texts to all soldiers too. Anticipating ‘trouble abroad’, Lawrence ensured that the Y.M.C.A and other missionary societies were allowed to help only on condition they did not ‘proselytise’. He appointed ‘caste committees’ from among the convalescents to advise on all manner of cultural sensitivities, particularly in relation to the catering. He arranged with the India Office for weekly trips to the tourist attractions and famous landmarks of London and organised supervised walks around Brighton, with trips in ambulances for those unable to walk.

The Indian Soldiers Fund provided items such as gramophones, books and puzzles and a Brighton woman, Mrs. Bailey, founded The Indian Gift House to organise treats and weekly organ recitals. At Lawrence’s suggestion, patients wrote their own newspaper. Printed in London, Akhbar-i-Jang was available in Urdu, Gurmukhi, and Hindi, containing censored news of the war that paid particular attention to incidents of Indian bravery. It proved to be extremely popular, with a weekly distribution of 32,000 copies to troops serving on many fronts.

The local, the national and even the international press were entranced by the thousands of Indian soldiers in an English seaside town. Mrs. Malcolm Ross, special correspondent for New Zealand’s Wanganui Chronicle, wrote in August 1915,

The Pavilion at Brighton, that architectural freak of the Georges, is filled with wounded men. Driving along country roads one meets often char-a-bancs filled with men in the bright blue hospital suits, who are having an outing and thoroughly enjoying it. One waves to them and greets them as a matter of course, and if the girl is pretty it is quite likely an invalid may call something very choice indeed.

The military authorities were concerned about such interactions, as we will see, but the local newspapers retained a lighthearted tone in their accounts of the ‘martial races’ on their doorstep. Announcing ‘The Indians Have Come’, the Brighton Herald reported that the town’s public had been ‘agog’ to see the these ‘warriors from the East’ march through Brighton, but were disappointed by the discreet manner in which they were admitted to the hospitals. Brightonians felt they deserved ‘a little more spectacle for their money’. The Brighton Herald found some consolation in telling its readers of an incident in which an Indian soldier had spontaneously picked up a white child, encouraging other mothers to hand their children over, in a ‘comedy that aroused pearls of laughter’.

The Brighton and Hove and South Sussex Graphic published some ‘interesting facts’ about ‘Our Indians’, that included data from the Indian census broken down by religion, a list of the primary crops cultivated in India, a brief description of different ethnic groups (Sikhs described as a ‘splendid race of fighting men’ and Gurkhas noted for their ‘fearlessness in the fighting line’). For those interested it also included the number of Indians killed by tigers in 1903. A Brighton Herald issue including pictures of the Royal Pavilion wards elicited unprecedented sales, with demand for reprints continuing well after the date of publication.

Imperial Anxieties Come Home

There was more to Lawrence’s solicitude for his patients than his obliging nature. It was immediately apparent that the hospitals were highly charged nodal points connecting Britain and India, crackling with all the tensions besetting the Raj. Both the India Office and the War Office continually reminded Lawrence of this wider significance and he wrote to reassure Kitchener, ‘I will never lose an opportunity of impressing upon all those who are working in these hospitals that great political issues are involved in making the stay of the Indians in England as agreeable as possible’. Lawrence was acutely conscious of anti-colonial agitators in India waiting to ‘make political capital’ out of any error he might make.

Britain’s war was not only against Germany but also Turkey, the seat of the Khilafat. This angered many Indian Muslims, who were still upset over the decision to repeal the Partition of Bengal after Swadeshi (self-sufficiency movement) riots. British officials’ fear of pan-Islamism was exacerbated by Turkish and German propaganda encouraging Indians to throw off British rule and ‘share the glory of being a free nation’. The Ghadar movement, founded in 1913 by expatriates residing in the USA to fight for Indian independence, had achieved an international following and regularly published newspapers that circulated throughout India and America. At the outbreak of the war, hundreds of Ghadrites had returned to India to fight for independence against the British. Despite their failure to generate wholesale resistance, they carried out 51 political murders from 1914-1916.

Hardinge was, if anything, even more concerned by non-violent agitation. Following his release from jail in 1914, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, one of the founders of the Swadeshi movement, allied with the British Theosophist leader and Irish home rule advocate Annie Besant to reunify the Congress, a move that paved the way for the Lucknow Pact of 1916 with the All India Muslim League. Tilak and Besant continued to press for Indian Home Rule, Besant declaring that ‘England’s need is India’s opportunity’. Hardinge met this mobilisation with repression, the Defence of India Act 1915 granting the police greater powers to detain without trial and censor the press.

These events might have been taking place over 4000 miles away, but Lawrence felt their repercussions in Brighton. Hardinge wanted recovered soldiers’ recollections to increase British ‘prestige’ and consolidate ‘the attachment the lower classes have to the Sirkar’. At one point Lawrence objected mildly that special treatment in England might spoil them for their return to the Indian Army ranks, where they were expected to provide their own bedding, clothing and food, and were often lacking in medical equipment. However, he appreciated that British India itself was ‘on trial’ within his hospital grounds.

Lawrence was placed in an extremely difficult position. He was expected to act as if there was no difference in status between Indian and British soldiers. Yet, as everybody knew, there were great differences. The India and War Offices insisted on certain racial distinctions even as they told Lawerence to erase others. If the exclusive rule of Britons in India was to be maintained, the British in general must be considered fundamentally superior to the mass of Indians. The sanctity and prestige of white women was especially important.

In 1915 the Rajah of Puduto defied official orders by marrying a white woman. Hardinge was infuriated, insisting upon his ‘fixed intention to keep the white race pure’. Both Kitchener and Hardinge emphasised to Lawrence the importance of keeping the Indian men in Brighton well away from white women. As the censor of the soldiers’ letters put it, news of liaisons there might encourage volatile Indian subjects ‘to conceive a wrong idea of the ‘Izzat’ [honour] of the English women. A sentiment which if not properly held in check would be most detrimental to the prestige and spirit of European rule in India’.

Both potential parties in sexual encounters would have to be policed. The most pressing issue was the white female nurses volunteering in some of the hospitals. In May 1915, following the publication of a photograph of a white nurse standing by the bedside of a soldier in the Daily Mail, Kitchener demanded the removal of female staff. Lawrence immediately withdrew the Queen Alexandra Nursing Reserve from the Brighton hospitals. Dr. Charles of the private Lady Hardinge Hospital, however, resisted, arguing their employment was integral to his operations and quite possible without scandal. The situation was finally resolved when the new Secretary of State for India, Austin Chamberlain, declared that they could remain.

Colonel Bruce Seton, Commanding Officer at the Kitchener Hospital, characteristically took the harshest line. He believed that it was not just nurses but local women who harboured a risk of the ‘gravest scandal’. Lawrence was more emollient, writing to Kitchener and Hardinge that he had been careful to avoid ‘running into dangers arising from women’, and was keen to dispel such ‘myths’. Despite great ‘temptation’, the behaviour of his patients had been ‘gentlemanly’. Just in case, though, both patients and staff were kept under strict surveillance, never allowed outside without a senior British officer, while Lawrence kept in close communication with Brighton’s Chief Constable to ensure that the local police kept watch.

Seton’s control at the Kitchener Hospital was paranoid. He insisted on confining not only most of the patients but the Indian staff too. Only the higher-ranks were permitted occasional walks under the supervision of English officers and closely guarded ‘route marches’ across town. He had barbed wire installed on all walls and imposed harsh penalties for breaking out: six men were flogged and one sentenced to six weeks imprisonment in the nearby town of Lewes. Additionally, Seton formed a military police guard from 44 convalescent patients to ensure that the hospital became a prison. They prevented any communication or passing of items, especially alcohol, from the outside. For one Indian subassistant surgeon, unnamed in Seton’s report, the incarceration proved too much. He fired a gun at the commander, narrowly missing. He was tried for attempted murder and sentenced to seven years imprisonment.

The propaganda that Lawrence generated for Indian consumption contrasted greatly with the reality of Seton’s regime. It centred on the King’s and Queen’ visits to the wounded soldiers. These not only boosted morale for the patients, but also had the most useful ‘political effects’. The King’s visit of 25 August 1915 was particularly commemorated. Photographs of the occasion were presented to all patients, with copies sent to India as evidence of the emperor’s concern. Filmed footage of the King awarding the Victoria Cross to Jemadar Mir Dast was also disseminated.

Hardinge was eager to receive such material, although Lawrence initially rejected an account of the hospital produced by Colonel J.N. Macleod because it neglected the citizens of Brighton’s role, especially that of Mrs. Bailey. Macleod replied,

As I wrote the account for its effect in India I tried to bring out the Pavilion was a Royal Palace and that the initiation of all that was done came from the King. To bring in the Corporation or Lord Kitchener more prominently I thought would confuse the egos of India. To give more details of the transfer of the Pavilion might emphasize the fact that the Pavilion is no longer a Royal palace which would minimize the political impression we want to make in India.

Lawrence commissioned the Corporation of Brighton to produce an alternative. The author was Henry Roberts, Director of the Public Library, Museums and Fine Art Galleries, who acted conjunction with Macleod. The resulting publication was entitled A Short History in English, Gurmukhi & Urdu of the Royal Pavilion, Brighton and a Description of it as a Hospital for Indian Soldiers. It begins with a brief history of the Pavilion, detailing its erection in 1820 and subsequent use as a palace for visiting members of the Royal family, with no attempt to disguise the transfer from royal to corporation ownership in 1845. However, the desire to overstate the King’s involvement remains, with the declaration that the hospitals were formed at the King’s suggestion. The combined effort of Mrs Bailey and the citizens of Brighton is presented as a debt that India owes Britain for taking care of its sons. ‘Brighton has thus come nobly to the help of the Indian Army, and the prompt and generous action of the Brighton citizens will never be forgotten by India’. There was a clear message for Indian nationalists: ‘a Sepoy was heard to say: ‘He (the King) is a listener. All we want in India is a listener. You saw that he listened and that is enough’.

As for the Soldiers?

The main evidence of what the convalescing soldiers themselves thought comes is in the form of the censors’ weekly reports on their letters home. These contain substantial reproductions and extracts from the originals, most of which were dictated to a scribe who was well aware that what he wrote might be redacted or stopped.[2] Many tried using ‘secret code’ to refer to unauthorised activities and sentiments. The censors were wise to much of this, blocking military information, demoralising accounts of the war and references to white women. Redactions were also made, for incitements to crime, reference to drugs, slighting reference to white people, and complaints about their treatment.

Both Lawrence and Second Lieutenant E.B. Howell, the chief censor, worried about the changing tone of the letters as the war progressed. The initial pride in service and optimism that Germany would soon be defeated had waned by March 1915 when Howell reported ‘The feeling of total despondency is rife as usual, but it is generally tempered to a certain extent by the resignation to or belief, in a higher power’. Soldiers arriving in Brighton described the war as ‘hellish’, and caused Howell consternation by writing home hoping to discourage family members from joining the army. Lawrence was especially concerned when patients attempted to tell contacts in India that the Indian soldiers’ lives were considered more dispensable than those of British soldiers. The censors worked out that the code adopted was ‘red pepper’ for British soldiers and ‘black pepper’ for Indian:

Please let me know what is the condition of the market for black pepper. That which I bought with me has all been finished and some more has been sent (.) You probably know that there is lots of red pepper but they want black.

Lawrence assured the Indian soldiers constantly that they were not considered mere cannon fodder.

Generally, however, the convalescents sent home favourable impressions of Brighton itself. Ghulam Mohiyudin described it as being ‘like heaven’ in comparison with other countries. Gender roles were noted favourably, one soldier writing, ‘it is the same for men and women, both men and women please themselves, they cannot forbid one another’. Despite the restrictions on contact with white women, the lack of the everyday racial discrimination of British India impressed one soldier: ‘the people are so very good that they make no difference between black and white’. Another wrote, ‘When one considers this country and these people in comparison with our own country and our own people, one cannot be but distressed’.

The letters suggest that the King’s visits had their anticipated effect. One soldier declared a reluctance to return to India as he was now in the ‘land of our King’. Those who met the monarch felt honoured and many were overawed to be staying in a building once inhabited by the King, some believing, as Macleod had intended, that it was still a royal palace. A patient in the York Place hospital described his days as passing with ‘joyful ease’ as the government ‘showers benefits upon us’ and many reassured their families that their religious requirements were being met.

The praise was not, however, universal. Raja Khan at the Kitchener Hospital, where Seton appears not to have emulated Lawrence’s care over religious protocol, wrote that the ‘arrangements are such that it is impossible to distinguish a Mohammedan from a Hindu’. The biggest gripe was the restrictions on the soldiers mobility as they recovered from their wounds and sought to explore their surroundings: ‘The people here are most friendly and liberal minded but we have no freedom’. Ghulan Haidar wrote that ‘England is a very fine country but we are treated like prisoners’. Unsurprisingly, most such letters came from the Kitchener Hospital. Gurkha Jemander Damodhar told his family that ‘I am not allowed to write full details as you know’, but this did not deter others from trying.

Despite Lawerence’s assurance to Kitchener that his patients were ‘gentlemanly’ around local white women, the censored letters reveal some subversion. Even from the Kitchener Hospital, Nabi Bukhah wrote,

I wish we should have come here in our young age to pass several examinations free of charge. English girls are very free in their nature and they love Indians very much. Love making and breaking in Europe is nothing but a matter of choice, friends are plenty when purse is full.

Most references to white women, be they nurses or town dwellers, however, were more circumspect. Here again code was employed, with white women referred to as different kinds of fruit, the most common being ‘pears’ or ‘apples’. As with ‘pepper’, such efforts rarely deceived the censors. The following example was redacted for ‘immorality’ in the censor’s report: ‘Here there are many pears of the kind you have in your garden. They encounter our people on our walks and we sit down and enjoy them. Then we are put in jail’.

Closure

In late 1915, in response partly to low morale after many of their white officers had been killed, and the effect that another winter might have on them, and partly to the anxieties about prolonged exposure to white women, British commanders redirected the majority of the Indian soldiers away from the Western Front, to Mesopotamia and Egypt, with cavalry staying on until 1918. The south coast hospitals closed in succession with the Pavilion seeing off its last Indian patient on 16 February 1916 and repurposing to treat over 6,000 British soldiers with amputated limbs.

For almost two years, Brighton had been pivotal to the maintenance of British rule in India. Its hopsitals manifested all the contradictions of that rule. The British authorities and Lawrence in particular, were right to be concerned about notions that Indian soldiers’ lives mattered less than white soldiers, and anxious that stories of ‘loose’ white women reaching India could prove subversive. But they also saw that the legitimacy of imperial governance could be bolstered through English grandeur and manners, and pride in fighting for an emperor who ‘listened’. The soldiers too were perceived ambivalently, as both exotic heroes coming to the aid of the motherland and racial inferiors intent on sullying the virtue of Englishwomen. The connections that sprang up between Brighton and India in 1914-16 worked both for and against the Empire.

Further Reading

K. Bacon and D. Beevers, The Royal Pavilion as an Indian Military Hospital 1914-1916, The Royal Pavilion, Brighton and Hove City Council, 2010.

Shrabani Basu, For King and Another Country: Indian Soldiers on the Western Front, 1914-18, Bloomsbury, 2016

Crispin Bates, Subalterns and the Raj: South Asia since 1600, London, 2007.

G. Greenhut, ‘The Imperial Reserve: The Indian Corps on the Western Front, 1914-1915’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 12, 2009, 54-73

R. Holland, ‘The British Empire and the Great War, 1914-1918’, in: J. Brown, R. Lois, D. Litt (Eds), The Oxford History of the British Empire, Vol. IV, The Twentieth Century, Oxford, 1999, 114-137.

Samuel Hyson and Alan Lester, ‘British India on Trial’: Brighton Military Hospitals and the Politics of Empire in World War I, Journal of Historical Geography, Volume 38, Issue 1, 2012, 18-34.

Philippa Levine, ‘Battle Colors: Race, Sex, and Colonial Soldiery in World War I, Journal of Women’s History, 9, 1998, 104-130.

G. Martin, ‘The Influence of Racial Attitudes on British Policy Towards India During the First World War’, Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, 14, 1986, 91-113.

George Morton-Jack, The Indian Empire At War: From Jihad to Victory, The Untold Story of the Indian Army in the First World War, Abacus, 2020.

David Omissi, The Sepoy and the Raj: The Indian Army, 1860-1940, Basingstoke, 1994.

David Omissi, ‘Europe through Indian eyes: Indian Soldiers encounter England and France, 1914-1918’, English Historical Review, 496, 2007, 371-396.

David Omissi, Indian Voices of the Great War: Soldiers Letters, 1914-1918, Basingstoke, 1999.

[1] This blog is based on an article first published in 2012, itself based on the undergraduate dissertation of the University of Sussex Geography student Samuel Hyson: Samuel Hyson and Alan Lester, ‘British India on Trial’: Brighton Military Hospitals and the Politics of Empire in World War I, Journal of Historical Geography, Volume 38, Issue 1, 2012, 18-34, ISSN 0305-7488, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2011.09.002. Full citations can be found there.

Samuel’s topic was inspired by an exhibition on the Pavilion as a military hospital: https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/discovery/history-stories/ww1-royal-pavilion/. We are very grateful to Kevin Bacon of the Royal Pavilion & Museums, Brighton & Hove, for supporting Samuel’s project and help accessing images before their digital open access. We would also like to thank Prof Raminder Kaur for her translation of the Gurmukhi text.

[2] The Indian soldiers’ letters have been published in David Omissi, Indian Voices of the Great War: Soldiers Letters, 1914-1918, Basingstoke, 1999.

[…] In the early stages of World War I, the Raj came to the south coast of England in the form of over 4,000 wounded Indian soldiers. They convalesced in a number of specially constructed hospitals, including in the Brighton Pavilion. Between 1914 and 1916 the former Prince Regent’s Oriental-style palace became charged with the hubris and anxiety of the largest and most diverse Empire the world had ever seen. [1] […]