The British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and former and current Home Secretaries Priti Patel and Suella Braverman are all second generation Indian East Africans. Families like theirs acquired a precarious status, subordinate to White settlers and officials but elevated above African subjects in the British colonies of southeast and East Africa. Indian intermediaries are most closely associated with the colonies of Kenya and Uganda. Notoriously, the post-independence Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expelled some 80,000 Indian subjects in 1972.

These communities took root mainly from the mid-1890s, but relatively few historians have appreciated that Sir Henry Bartle Frere, a famous antislavery reformer, had drawn up a scheme to employ Indian subjects in the management of colonised African people some twenty years beforehand. Frere was one of the first imperial officials to argue that certain classes of Indians could serve as a buffer between relatively few white officials and a conquered, dispossessed mass of African subjects.

There had been trading connections between India and East Africa long before the arrival of the British, with Indian merchants established in small numbers along the East African coastline. From the 1850s, tens of thousands of Indian labourers were recruited under contracts of indenture to work White-owned sugar plantations in the colony of Natal. Colonial planters there were following the precedent set by former slave owners experiencing post-emancipation labour shortages in the Caribbean and Central American colonies.

The Indian population in Uganda and Kenya owed its origins to the recruitment of labourers, mainly from the Punjab, to build the Uganda Railway from 1895. The track was laid at the cost of 4 Indian workers’ lives per mile, around 30 workers having been killed by the notorious ‘Tsavo maneater’ lions, mentioned in a series of parliamentary debates about funding for the railway in 1900. The Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury made a joke of the issue in the House of Lords, saying, “With respect to the lions, I feel bound to say something in their behalf. They are not so aristocratic that they will only feed on coolies; they took a medical man the other day, and I expect it will be found that they have taken many other people.”

The subsequent arrival of so-called ‘passenger Indians’ boosted the numbers who decided to stay in each of these southern and East African colonies, creating an Indian middle class whose lives were generally seen by British employers and administrators as less expendable.

Many of those migrating to Uganda were traders from Gujurat who saw opportunities for economic advancement. ‘Passenger’ Indians were attracted to Kenya mainly from the Bombay (Mumbai) region after the British East Africa Association (later British East Africa Company) was founded there in 1887. Although it later moved its headquarters to Mombasa, it already employed Indian accountants, guards and officials. Many more Indians arrived once the Company had morphed into the East Africa Protectorate in 1895, with the rupee as its currency and its law imported from British India.

Some British officials envisaged developing Kenya as the ‘America of the Hindu’, with middle class Indians as intermediaries who would help the British lead Africans towards ‘civilization’. However, when White settlers claimed the best land in the highlands, Indians already living there were expelled. In 1927 Indians won the right to five seats on the legislative council. Although Europeans had eleven seats, Indian representatives agreed that Africans should be excluded entirely.

After independence, Kenyan Indians were not expelled in the same way as those in Uganda, but policies of Africanisation and anti-Indian discrimination persuaded many of them to utilise their British citizenship and emigrate to the UK along with the expelled Indian Ugandans.

The employment of Punjabis in the Kenyan police during the early twentieth century is relatively well known, but what is not often appreciated is that Bartle Free’s scheme predated these developments by some two decades. Although his vision never came to pass, it is worth telling Bartle Frere’s story for what it reveals about imperial men’s utilisation of the links between India and eastern Africa.

Bartle Frere: Governor and antislavery activist

The young Bartle Frere graduated top of his year at the East India Company’s Haileybury College. His first employment was as a writer in the Bombay civil service. In 1842, he was promoted to private secretary to George Arthur, Governor of the Bombay Presidency. Within two years he was married to Arthur’s daughter, Catherine. By 1847, he was the Company’s Resident in Satara, one of the first princely states to be subject to Governor General Dalhousie’s doctrine of lapse and brought under direct East India Company rule. From there, he moved to Sind, where he guided the installation of a postal system based on Britain’s, which was subsequently adopted across India.

Frere’s swift action during the Indian Uprising in 1857, sending troops to support British forces in the Punjab, earned him the thanks of both houses of parliament and a knighthood. His promotion of literacy in the Sindhi language was rewarded with membership of the Viceroy’s Council in 1859, and in 1862, he succeeded his father-in-law as Governor of Bombay. Frere sought to use his authority for modernizing, liberal projects. He is remembered in Mumbai as the driving force behind the Deccan College at Pune, famed for instructing Indians in civil engineering. The city’s growth led to his being appointed to the Secretary of State for India’s Council of India when he returned to London in 1867.

Frere’s imperial career transcended India in 1872, when the Foreign Office commissioned him to travel to Zanzibar. Whilst governor of Bombay, Frere had hosted David Livingstone as he prepared for his expedition to find the source of the Nile. Frere seconded a number of Bombay army sepoys to accompany the expedition and, in January 1866, sent it underway to Zanzibar in a Bombay government steamer. Livingstone had then famously disappeared, at least as far as the British public were concerned, until 1871, when the American journalist Henry Morton Stanley found him on the shores of Lake Tanganyika.

At the same time that British writers were elevating Livingstone into an icon of Christianity, Commerce and Civilization, Frere was helping to lead a revived antislavery campaign. A high churchman and a member of the Antislavery Society, he had long condemned the ‘fashion of looking down on all men who differed from us in colour or in race.’ He also bemoaned the British public’s general ignorance of the Arab-led East African slave trade.

It was Frere’s well-known position on Arab slavery that led to his next employment on behalf of the British imperial government. The Foreign Office was concerned that Barghash bin Said, the sultan of Zanzibar’s, support for an Islamic revivalist movement threatened British control of the region. The convergence of a popular British lobby against Zanzibari slave trading and this strategic interest led to Frere’s appointment as British envoy to the sultan. Frere was given the autonomy to draw up his own instructions.

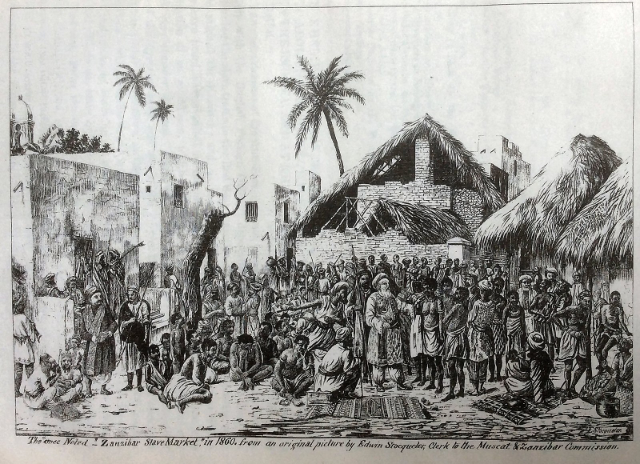

When he arrived in Zanzibar he found that Barghash was emboldened by the French promise of support for his independence. Frere acted immediately, ordering the Royal Navy to seize any slave ships sailing between Zanzibar and the African coast. He then threatened Barghash with a total blockade. The Foreign Office was obliged, belatedly and somewhat reluctantly, to approve of his forceful actions. Barghash was forced to close the slave market, end the import and export of enslaved people, and ban British subjects, including Indians, from owning enslaved people. Arab slave owners, however, were left in possession of their ‘property’. Bargash’s promised French support never materialised.

By the mid-1870s Frere was famous in Britain as a proponent of liberal education, civic investment, modernization and antislavery. By the end of the decade, though, he was the Empire’s leading warmonger.

Warmonger in Chief

During the 1870s the Colonial Office was encountering difficulties trying to confederate the separate British colonies, Boer republics, and African kingdoms of South Africa. Given Frere’s success in Zanzibar, they turned to him for assistance. In October 1876, Lord Carnarvon, the Secretary of State for the Colonies, offered him a “special” appointment, rather than an ordinary governorship. He would be equipped with far more power than the governors of the existing British colonies of the Cape and Natal and, as High Commissioner, would also be commander-in- chief of all British military forces in the region. The normal gubernatorial salary was supplemented by an imperial grant of £2,000 and he was promised a peerage if he succeeded in effecting the merger of the region’s fractured governments.

Frere’s first task was to incorporate the lands of the still independent Gcaleka Xhosa in the Transkei, a region which, along with Mpondo territory, separated the Cape from Natal. He seized upon the pretext of a fight between some Xhosa men and Mfengu, who were allies of the Cape Colony, to declare war, announcing that the Gcaleka king, Sarhili, was deposed. Frere anticipated that the Xhosa territory would be governed indirectly, in the way that he had once overseen Satara on behalf of the East India Company. When British troops entered the Amatola Mountains in March 1878, however, they were ambushed repeatedly. In the end, it took a well-organized system of mounted units pursuing scorched earth tactics to secure Sarhili’s surrender.

By mid-1878, Frere’s plan was coming to fruition. The last independent Xhosa chiefdoms, were being subjected to British authority through Resident Agents backed by British troops. His next target was the powerful Zulu kingdom on Natal’s northern, and the Transvaal’s eastern, border.

In London, however, the government was losing its enthusiasm for South African confederation. The renewed threat of a war to prevent Russian expansion in the Balkans meant that colonial military commitments had to be scaled back. A new colonial secretary told Frere, ‘it is the desire of Her Majesty’s Government not to furnish means for a campaign of invasion and conquest … I can by no means arrive at the conclusion that war with the Zulus should be unavoidable, and I am confident that you … will … avoid an evil so much to be deprecated as a Zulu war’.

For the second time in his career though, Frere was determined to act independently. On 11th December 1878, he presented Cetshwayo with an ultimatum. In the time-honoured tradition of justifying unprovoked attacks on independent peoples, he claimed that he was acting ‘on behalf of the Zulu people, to secure for them that measure of good government which we undertook to promise for them.’ The Zulu king was told that he had until 10th January 1879 to fulfil a number of conditions. Among other things such as the payment of fines for various alleged misdemeanours, Cetshwayo must disband his army and discontinue the Zulu military system, based on age-group cohorts of men known as amabutho (inaccurately likened by the British to their regiments). He must abandon his control of amabutho-based marriage arrangements, give freedom to missionaries to convert Zulu subjects and, of course, accept a British Resident Agent to oversee the kingdom’s future governance.

Once the Colonial Office heard of Frere’s provocations, it replied:

‘… the communications which had previously been received from you had not entirely prepared [the Colonial Office] for the course which you have deemed it necessary to take … I took the opportunity of impressing upon you the importance of using every effort to avoid war. But the terms which you have dictated to the Zulu king … are evidently such as he may not improbably refuse, even at the risk of war; and I regret that the necessity for immediate action should have appeared to you so imperative as to preclude you from incurring the delay which would have been involved in consulting Her Majesty’s Government upon a subject of so much importance.’

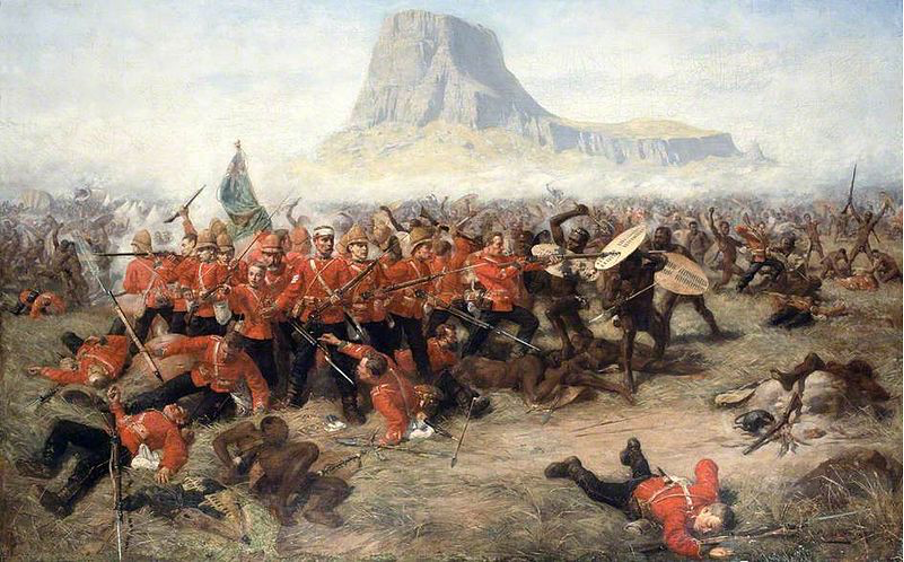

By the time this admonition reached him, Frere had already launched the invasion of Zululand with 18,000 troops, and also encountered a disastrous setback: the loss of nearly 1,700 men at the Battle of Isandhlwana.

Frere’s Scheme for the Zulu

After Isandhlwana, Frere spent the time awaiting reinforcements from Britain planning for the post-war occupation of Zululand. What Frere had in mind reverted once again to his Indian experience. He requested that the Colonial Office mediate with the India Office and War Office to send him Indian soldiers – sepoys – to assist in the control of Zululand.

Frere wrote,

‘There are objections of race and colour, which would be obstacles to an experiment anywhere but in the neighbourhood of Natal, where Indian Coolies are already present in considerable numbers [on the colony’s sugar plantations]; but Sepoys would probably be found very useful in garrison between the Drakensberg and the sea, anywhere from the Kei northwards to the Limpopo … Sepoy Regiments do not suffer either in health or discipline from being cut up into small detachments as European Regiments do … for a very moderate allowance of hutting money, they provide their own quarters, and do not require permanent barracks, and … the pioneer regiments do an immense deal of useful engineering work … When the strength of the Zulu Army is once broken, and the people relegated to their natural pastoral and agricultural avocations, it would take a very small force of Sepoys to keep 400,000 of them in order with the aid of a good Zulu police. I have Zululand in view rather than Natal, in the above observations; but if any Indian authority would consider the force necessary to keep in order a million of men of the most martial races in India, he would probably name a garrison very much smaller than anything yet contemplated for Natal and Zululand combined’.

Once discharged, Frere continued, the imported sepoys could join the ranks of the indentured workers occupied on Natal’s sugar plantations and in the colony’s trade, ‘though a Madras Sepoy would probably find himself more at home at once among the Indian Coolies than Sepoys from other parts of India.’ As for the existing Indian population of the colony, ‘that … material is generally much inferior to the Indian Sepoy of the same race – the ordinary Sepoys are the finest of the population, while the ordinary coolies who emigrate, are often the poorest and weakest.’

The Colonial Office response was lukewarm. It referred the matter to the War Office, asking it to estimate the relative costs of maintaining Indian and British garrisons overseas. This information, it suggested, might be obtained best from the dual British and Indian garrisons maintained in Malta. The Colonial Secretary himself commented that, given the recent experience at Isandhlwana, ‘the Zulu or Kaffir is, man for man, better than the Sepoy – and that therefore this experiment might be dangerous.’

The nail in the coffin for Frere’s scheme was advice from the India Office that the terms on which sepoys might accept service in South Africa ‘would certainly require a considerably higher rate of pay than the Government of India give for Indian service, even across the seas’. This led the Secretary of State for India to doubt ‘whether the charges would fall so far short of those of British Troops as would compensate for the difference in value of the two classes.’

All this remained speculative, of course, until the disaster at Isandhlwana could be reversed and the Zulu defeated. This was finally achieved with the Battle of Ulundi and the subsequent fragmentation of the Zulu Kingdom.

In the meantime, Frere had transitioned from an improving administrator of India and antislavery activist to a rampaging conqueror of independent African kingdoms (in his pursuit of confederation he had also started wars against the Griqua and Pedi). His vision for an Indian-policed colony in Zululand was not to be fulfilled, although Indians came to constitute a significant proportion of Natal’s population. It was Gandhi’s experience of discrimination in the Transvaal that set him on the path of activism, initially on behalf of middle class South African Indians and later for all Indians.

I doubt that Frere’s scheme for Zululand acted as a direct precedent for the later East African colonial administrations, but what it does highlight is the way in which Britain’s imperial administrators thought of India as a resource not only of labour for other parts of the empire, but also of intermediaries to help them maintain control of that empire.

*Much of this blog is extracted from Alan Lester, Kate Boehme and Peter Mitchell, Ruling the World: Freedom, Civilisation and Liberalism in the Nineteenth Century British Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2021.

Where did you find the Lord Salisbury quote about the Tsavo railway workers? I haven’t been able to find the source — other than on Wikipedia.

Sorry it took so long for me to come across this question Craig – it got buried! That’s a really good point. For this blog I took wikipedia on trust when I should have known better. I’ve found references elsewhere to Salisbury having made such a remark – http://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/3rd-march-1900/11/the-lions-that-stopped-the-railway – but having searched Hansard I can’t find the exact quote. Salisbury certainly talked about the lions in the Uganda railways debates of 1900 – https://hansard.parliament.uk/search/Contributions?searchTerm=lions&startDate=01%2F01%2F1900%2000%3A00%3A00&endDate=01%2F01%2F1901%2000%3A00%3A00 – but so far I’ve had no luck finding these exact words either. Will now edit the post accordingly. Thank you!

Thanks for your message!

I just found the Salisbury quote — on page 104 of Patterson’s book.

Where can I get the names of the coolies who came to Kenya. Am trying to trace my origin

Good question! I think the best place top start looking is here: https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/indian-indentured-labourers/