One of the advantages of what we’re doing on this project is that we get to see how large-scale shifts in colonial governmentality played out in the daily business of the offices at the nominal centre of empire. In the circulation of documents and the rituals of administrative work, it’s sometimes possible to discern some of the processes of adaptation, improvisation and contention through which the imperial project continually remade itself, being played out in ‘real time’. In records of the East India Company during our first ‘snapshot’ of January-March 1838 (see our first blog for why it is we’re doing this in the first place), I’ve been particularly fascinated with the changes occurring in relation to steam navigation, and the Company’s attempts to adapt to and take advantage of this emergent technology in remaking the conditions of global power. In the next two blog-posts, I’ll be exploring some of the things I’ve found, and wondering how they fit into larger narratives of technology and empire.

“Conducted separately and without intermixture”: imperial and administrative contexts

In February 1838, the Court of Directors of the East India Company (with the ever-watchful Board of Control’s permission) issued a circular to all its agencies:

“It being desirable that our correspondence with the several governments in India upon Marine subjects or on Matters in any wise connected with Steam Vessels and their Establishment and Engines, with Steam Communications between India and England, with river or Sea Steam Navigation in general, and with the Master Attendants’ Departments or Dock Yards, should be conducted separately and without intermixture with other Departments as at present, we direct that all such subjects be addressed to us in future in the [Marine] ‘Department’ and that your Consultations and Proceedings on such matters be recorded in that Department.”

Essentially, the Company had just opened a new department: alongside its Military, Judicial, Revenue, Home, Ecclesiastical, and Political Departments, there was now one that dealt specifically with marine matters, and especially with steam.

Within the company, a department was not so much a physical space as a method for partitioning administrative workflows and defining policy areas. All official correspondence between England and India is classified by the agency concerned (from amongst the Government of India in general, the three subsidiary Presidencies of Bengal/Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay, and other agencies such as prince of Wales Island, St Helena, or China), and numbered according to their order in the year: so this inaugural Marine circular, for example, is designated ‘Marine Department, India, No. 1 of 1838’. Matters to do with steam navigation would still be decided by the same committees and individuals at all points of the administrative network; what the formation of a new department really signifies is a taxonomic move, by which the Company and Board recognised that here was a thing that needed to be responded to in a discrete and co-ordinated way: a field for specialised policy formation, for the consolidation of administrative attention and the concentration of expertise.

The Company’s reasoning for doing this is fairly clear: the correspondence relating to steam navigation and its effects is quite staggering, both in range and volume. Reading through this small mountain of paperwork, you get a vivid sense of a large global organisation scrambling to formulate a response to a new technology and adapt to the ways in which it refigures the whole practice of global power. The formation of the Marine Department marks the moment at which the Company began to firm up its policy towards steam: it’s the product, if you like, of a moment of commitment.

If this is a story of governmental and commercial power structures being challenged by new technologies, and attempting to control them, it’s hardly a new one. It’s hard to avoid a Silicon Valley-esque lexicon of ‘disruption’ and ‘paradigm-shifting’ when writing about this kind of thing, and interrelations between technology and geostrategy have proved fertile ground for historians of subjects that go far beyond nineteenth-century empire. (Check out, for example, Alex Wallerstein’s brilliant Nuclear Secrecy blog, which explores the dense imbrications of science, politics and geostrategy that made the Cold War.) It’s easy, sometimes, to get hung up on the distinction between motives and means: which came first, the desire to do something or the technology with which to do it? But naval engineering hardly occurs in a political void, and a desire to sail up rivers and enforce trade or conquest by violence didn’t sit around for centuries waiting for a suitable technology to bring it into the geostrategic toolkit. Close study of how governments and administrative structures respond to technological change, the ways in which policy and practice are generated, and the problems of applying and adapting those practices, might help us to understand this complex interplay a bit better. In doing the kind of study we’re engaged in – short, discrete ‘snapshots’ of governmental work – it might be possible to get a fine-grained sense of how, in committee rooms and offices, in the administrative procedures and cultures of imperial government, the capillary interplay of technology and policy played out.

The Company was, of course, used to technological innovation in the matter of navigation – sail and shipbuilding were hardly static technologies, and in 1838 we also find the Court exercising some deliberation over the type of sail fabric the ships of the company’s fleet should be contracting for. But steam presented an unprecedented technological shift. It was still relatively new: the first commercially successful steamship had begun operating in 1807; the first regular commercial sea-crossing between England and Ireland in 1816, the first transatlantic crossing in 1819; and the first steamships in Asian waters, the Diana and the Pluto, were built at Kidderpore in 1823 and 1824. Almost as soon as they were built, Diana and Pluto were used in the First Burmese War of 1825, sailing troops up-river to Yangon. In the late 1830s, larger and more complex craft began to be specially built in Europe and sailed around the Cape for Indian service.

“An Establishment of efficient Sea-going Steam Vessels”: steam’s potentials, and the Company response

The effects of steam on the Company’s way of doing things, and the ways these show up in the archive, can be roughly divided into two columns: the things steam can do, and the things steam demands.

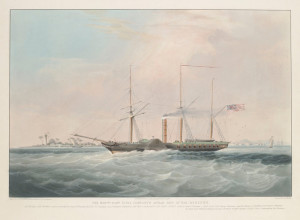

Steam propulsion offered speed, power, and consistency. Steamships were not only faster than sail; they weren’t dependent on favourable weather conditions or prevailing winds. The South-West Monsoon had severely limited travel from the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea towards Europe, enforcing a seasonal rhythm to trade and communication; steamships, with their ability to make way against prevailing winds (up to a certain point, at least), upended all this, promising a year-round service. This would have obvious effects on trade and military capacity, but the immediate change for the Company was communicational. Under sail, the time a letter took to travel between Calcutta and London could be anything up to four months – with, again, that seasonal issue of the monsoon making things more complicated. With four months each way, and the work of bureaucracy and implementation at either end, the cycle of administration – from making policy in London to hearing of its application, or from applying that policy in India to learning what the Court of Directors thought you should do next – was rarely shorter than a year. Aboard the Company’s brand-new steam cutter the Atalanta, the dispatches of March 7th, 1838 reached Bombay in a record 41 days, and Calcutta in 54. The usual route was through the Mediterranean, with French packet steamers from Marseilles to Malta, a mail steamer from Malta to Alexandria, and then a short overland hop to the Red Sea, where a Company steamer – in 1838 the Atalanta and the Berenice, paddle-wheel hybrid craft with sails and gunports – would take them onward into the Indian Ocean. With the transit time of information halved, and no longer so dependent on seasonal variation, the policy cycle could be shortened too: the obvious multiplier effects of faster ships on trade and communication applied to government, too.

The Company steam ship Berenice, built 1837. Note the traditional gunports along the aft side. (William John Huggins, 1838. © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.)

The records bear this out; in early 1838 the Company is palpably anxious about re-engineering its communicational networks, and its hunger for information generates an enormous correspondence. Frequent letters go out to Col. Patrick Campbell, the Agent in Alexandria. One of the major stresses of Campbell’s job is to manage a communicational bottleneck: most of the correspondence and many of the people passing between India and England have to cross the short isthmus between Alexandria and Suez. Campbell has to travel constantly between Cairo, Alexandria, and the Red Sea ports of the Gulf of Suez, reporting on the arrival and departure of the Malta steamer, arranging for janissaries to escort the mails over the isthmus, and answering the Company’s often rather plaintive enquiries as to how best to tweak the network for maximum efficiency. Should the Malta steamer, for example, run monthly, as now, or every four weeks? Campbell is non-committal, but a small policy dispute begins to blow up between the Court and Board of Control. The attention paid to the minutiae of how to make the network run as smoothly as possible is impressive: a delay of a day has to be explained.

Steam – and the iron hull technology with which it developed in tandem – also offered new ways of projecting geostrategic force. While the steamboat’s manoeuvrability and capacity for being pointed whichever way you wanted it to go made riverine navigation much easier, the structural efficiencies of iron hull construction made the river gunboat possible: steamboats could carry heavy ordinance and troops up shallow inland waterways.

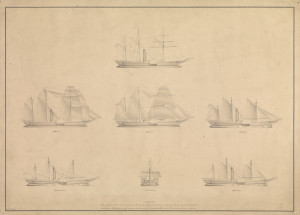

‘Diagram Elucidating the principle on which the Honble East India Company’s Steam Vessel Atalanta is Rigged, Displaying the greatest spread of Canvas, with least resistance from Masts’ (1836). The Atalanta and Berenice could function under sail, steam or both, depending on prevailing wind and conditions. (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.)

But if the Company was well aware in 1838 of the geostrategic potentials of iron-hulled steamboats and warships, they were also in possession of a private navy which was struggling with poor morale, poor organisation, and an existential uncertainty over its purpose and its future in the face of steam technology. In 1837, William Bentinck MP had called a Parliamentary Select Committee on the issue. Having heard amongst others the opinions of several Company servants, Bentinck recommended that the Indian Navy (IN) be reconstituted as the Indian Flotilla, constituted entirely of steam vessels, with an increased focus on river navigation, and brought for good measure under the supervision of the Admiralty. In January and February 1838, we find the Company preparing a major reorganisation. Sir Charles Malcolm, Superintendent of the IN, is to be replaced by Capt. Robert Oliver, the latter having spent his career so far in the Royal Navy and being – unlike Malcolm – well-versed in steam technology. This is a popular move: although Court deliberations and dissents evince some disagreement about the choice of officer, there is no resistance to the idea that, if the Court wishes the IN to avoid being absorbed by the superior RN, they will have to catch up with their technological savvy. Steam vessels are not to entirely replace steam – as several member of the Court and the Indian establishment point out, entirely getting rid of a fleet of sailing ships seems a rash move – but a concerted push will be made to modernise the fleet. Here, as elsewhere, the records betray a certain sensitivity in the Company’s sense of precedence. In the constant back-and-forth over dispatches between the Court and the Board (nothing can go out to India until the Court has signed off on it, and they make frequent alterations), there is a short struggle over whether the IN is to be renamed the Indian Flotilla: eventually, and rather uncharacteristically, the Board concedes to the Court’s pride, and allows the name to stand as it is.

One Court dissent from February, by John Forbes, demonstrates some of the policy debates within the East India House. He objects strongly to the plans as they stand for slowly shedding the sail component of the fleet, reminding the Court that sailing-ships are essential in maritime surveying, and that should the Company end up offloading its sailing craft on the RN, they might leave themselves more open to an effective takeover should they ever want them back. He’s also critical of the Court’s sheer haste: he understands, he writes, the need to keep up with the French and the Russians, but suggests that a policy of crash modernisation with minimal budgetary constraints bears risks, especially given “a People [Indians] overloaded with taxation”: the sense is that the Company is threatened on the one side by a government which would welcome any opportunity to bring it to heel, and on the other by the potential resistance of its colonial subjects. He also needles at the Company’s characteristic meanness, wondering whether the failure to award a pension to Malcolm, and the reduction in pay for the post, might not lead to jobbery, place-hogging, and a blow to the Navy’s prestige – how, for example, is a high-ranking officer of the IN to fulfil his social obligations with a lower salary than that of his equivalent in the land forces?

Finally, the Court sends out a document that’s as close to a statement of policy as they’ll get. Marine Department (India) letter no. 5 of 1838 (dated 7th March, which rather appropriately makes it part of the Atalanta’s record-breakingly fast package of dispatches) sets out its stall with unusual force. Noting the sad state of the steam fleet at Calcutta, the Court writes:

“It is of the highest importance that your Govt. shall possess an Establishment of efficient Sea-going Steam Vessels, not only for the various ordinary purposes to which your present Steamers have been applied, but of a size and power to make them available as Transports and for the effectual Check of Piracy, and we are of opinion that three of such Vessels will not be more than adequate to your wants.”

To some extent, Forbes proves to have been right about the Company’s almost indecent haste. The Government’s last letter reported their having decided, on their own initiative, to commission a new vessel at Bombay and fit the engines of one of the moribund steamers into it. For an organisation engaged in a constant fight to assert its control over the Indian establishment, especially in budgetary matters, the Court’s assent to this is unusually even-tempered:

“Although these proceedings are contrary to our orders of February 1836 which forbad ‘the thorough repair of old Vessels or Engines or the building of new Vessels’ to be undertaken, we shall not under the peculiar and unforeseen circumstances in which you were placed by the simultaneous failure of all your Vessels, withhold our sanction … you must not however consider this relaxation of our positive injunction in respect of building and repairing Steam Vessels, as justifying any departure from them on future occasions.”

The letter they’re replying to is dated July 1837; the Company can hardly do much about a decision long since taken and money long since committed; withholding sanction from a fait accompli would only make plain the basic problem of asserting any real control that we’ve alluded to in previous posts. But in the weakness of the Court remonstrations, there may also be a consciousness that the urgency of building up steam capability outstrips the pace of imperial communications. It will be nearly a year between the Government informing the Court of their decision, and the Court sending back its half-reluctant sanction: even if steam itself speeds up this glacial policy cycle, the technology, and the ways in which other people are applying it, might move faster than that.

There’s also a fear that that pace of development might outstrip even the nimblest attempts to keep up:

“The repairs of Steam Vessels is at all time a questionable proceeding by reason of the continual improvements that are being made in the construction of such vessels which improvements are seldom, if ever, capable of being applied to old Hulls; and if the repairs are very extensive, it may be more economical in the end and certainly more advantageous to build a new Vessel than to alter and patch up an old one.”

Why spend money on outdated technology? Steam comes into focus here in its full disruptive force, as a technology which can’t really be bargained with but has to be committed to in order to maintain power. Besides, there are other things to focus on, like the usefulness of steamboats on rivers: anticipating “increased benefit from the extension of their Sphere of Employment” the Court wants to send steamboats up the Ganges past Allahabad, and eastward up the Brahmaputra into Assam. This is not only to project force and enhance the military control of territory, useful as that is in a period during which the Company is also aggressively pursuing the subordination of princely states, and issuing orders for the destruction of recalcitrant local feudatories’ forts: they have also calculated that they can make a saving of 12,000 rupees per annum by discontinuing military escorts for boats carrying treasure. With a proposed six more iron-hulled, shallow-draft river steamers, four new accommodation boats for soldiers, and some provision for training, the Company can use six sepoys and the river-gunboat’s concentration of firepower and stores to do the job of a much larger and logistically-challenging escort.

These aren’t all the documents to do with steam navigation that have turned up in our 1838 snapshot. So far I’ve only covered what steam offered: in Part 2, I’ll focus on the things it demanded – the infrastructure and human and technological capital it needed to extend a viable global reach – and how the Company dealt with the challenges of engineering such a huge technological shift in their operations.

Leave a Reply