Alan Lester

Colonial Realities

Colonialism is, by its very nature, incompatible with many of the ideals of justice that we hold dear today. The definition of the word, according to the Oxford Online Dictionary, is “the policy or practice of acquiring full or partial political control over another country, occupying it with settlers, and exploiting it economically.” As that three-part definition suggests, no form of colonialism ever developed without great, unprovoked, violence.

My specialism is the British Empire, in all its complexity over 300 years, across 25 per cent of the Earth’s territory at its height and including over 40 colonies by the C20. In my last research monograph I tried to examine how that incredibly complicated entity was governed everywhere and all at once during certain moments of the C19. Unfortunately, the British Empire was no exception to the rule that colonialism entails unprovoked violence on a large scale. Let me take the three parts of the Oxford definition of ‘colonialism’ to sketch out how the British Empire in particular was established and operated.

Political Control

First, the acquisition of political control. Since, by and large, people don’t want to be colonised by outsiders, it should come as no surprise that this was obtained, for the most part, violently. The Caribbean colonies were seized from prior colonial occupants – mainly Spanish and French – after they had already overseen the genocide of the region’s indigenous peoples.

North America, Australia and New Zealand were taken with the displacement and dispossession of indigenous peoples by emigrant British settlers indigenous allies, with the frequent killing of those who resisted; India was obtained by the East India Company through a combination of actual and threatened armed force as well as negotiation.

A British gunboat during the invasion of the Waikato, New Zealand, 1863

In the second half of the C19 alone, over sixty colonial wars were launched by Britons establishing political control over southern, Western and Eastern Africa, Afghanistan and parts of the Middle East. Colonel Callwell wrote a famous field guide to winning such ‘small wars’ as the British called them. But these invasions, expeditions, raids, battles and massacres were anything but ‘small’ in their consequences for the people killed, displaced and subjugated and for the societies broken by them. It is impossible to calculate how many people were killed in Britain’s imperial conquests between the C17 and C20, since they were never systematically counted, but from the estimates we have of recorded conflicts, it is safe to say they number in the millions.

Occupation

The occupation of settlers – the second part of the definition of colonialism, resulted in the decimation of indigenous peoples, as a result of both newly introduced disease and violence. Through meticulous ongoing research we now know, for example, that Aboriginal Australians were displaced from their land not only by smallpox, but also with the assistance of hundreds of separate, small-scale massacres, breaking up particular groups or clans. Those First Nations, Native Americans and Aboriginal people who survived the occupation were forced to give up their cultures and even, in many cases, their children, so that they could be assimilated to the new, White colonial society.

Economic Exploitation

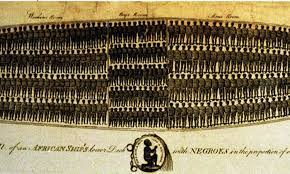

The third part of the definition of colonialism – economic exploitation – took various forms within the British Empire. Perhaps the most notorious was the capture and trafficking of over 3 million people on British ships, out of a total of 12.5 million, to be used as slave labour in the commercial plantations of the Americas – a form of slavery never before seen in human history. The sugar, tobacco, cotton and other commodities that this chattel workforce produced was part of a process that transformed three continents. Between the C16 and the mid C19, much of Africa was destabilised as African polities either participated in the trade by selling captives or succumbed to raids themselves; the ecology of the Americas was fundamentally altered as commercial plantations replaced indigenous plant species, and indigenous peoples were displaced, while Europe embarked on its Great Leap Forward with the assistance of the capital earned through the domination of enslaved labour. While the Arab slave trade had operated across much of the eastern side of the continent for a millennium, its effects were nowhere near so far-reaching or transformative of the world economy.

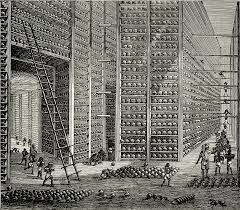

But while the slave trade is the best-known example of economic exploitation, and was of course brought to an end by campaigners in Britain in 1807, there was also the exploits of the East India Company. Once it had ceased to be a viable commercial trading entity, its business model consisted of extracting rent from Indians to send to British shareholders as dividends, and enforcing the production of opium in India, to smuggle into China, with which to buy tea for the European market.

The connections forged by these forms of colonial economic exploitation were truly global. The tea brought from China with narcotics from India was drunk in Britain sweetened with the sugar grown by slaves in the Caribbean. And those slaves were generated in turn partly by bringing cloth from India to trade for captives in Africa. Finally, when the British government was the first among European nations to free slaves in the Caribbean in 1833, the shortage of labour on Caribbean plantations was resolved by resorting to India again, for the recruitment of 1.5 million impoverished British subjects under indentured labour contracts.

So, I am afraid, like it or not, the study of British colonialism contains things that nationalists who believe in the timeless, fundamental goodness of Britons, really don’t want to hear, but which are essential to understanding how the whole system of empire came to operate. We may want to focus mainly on the British abolition of slavery, and indeed that’s largely what we have done until recently, but we have to recognise that it was only a small part of the story. It gets worse though.

Having established these three elements of colonialism – political control, occupation and exploitation – the modern European empires including Britain’s did something else that was quite novel. They associated status in their colonial societies with race, pioneering what we know today as racism.

Modern European Colonialism and Race

The European empires first created that association between status and race with the trans-Atlantic slave trade. This was the first slave trade in history in which only Black people could be enslaved. The Arab and ancient slave trades had no such hard and fast racial designation. In every colony sustained by Europeans, specifically racial hierarchies were imposed and maintained not just before but also, and to an even greater extent, after the abolition of slavery. As the historian of race Nancy Stepan has put it, the battle against slavery was won as the war against racism was lost. Even the campaigners against slavery, who saw its abolition through parliament (and who might today be condemned as ‘woke’), believed that colonialism in general was justified, because more advanced Europeans needed to rule more backward races in order to ‘civilise’ them.

While notions of scientific racism – the idea that Black people were biologically inferior to White people and could never match them – were often challenged, the notion that Black people would take hundreds of years at least to evolve culturally – was prevalent, seen even as ‘common sense’.

By the mid-C19, White men were in charge in every British colony and the ‘natives’ were expected to show deference to White women. Moral panics would break out periodically in most colonies over rumours of Black and Brown men threatening White women’s purity. Even the poorest White women generally had Black and Brown servants to do the domestic work thought to be part of a woman’s role, and corporal punishment of these servants was common. When Black or Brown servants sought prosecutions under supposedly non-racial laws, for masters and mistresses who abused them, their chances of success were infinitesimally small in the face of White juries and judges.

With the exception of certain indigenous elites, whose cooperation the colonial authorities required, especially in India, ‘ordinary’ Black people could find themselves ordered around and physically abused on the streets by even the lowest status White person, without any recourse to justice. Across the British Empire, for all its rhetoric of non-racial governance, racial discrimination was the everyday norm, with the degree of insult often finely graded according to ethnicity or skin shade. Access to jobs, the law, health care, education, democracy, justice and even the railways was by and large conditioned by race, no matter how much liberals in Britain might disown it.

In the colonies, racial views varied from the exterminatory to the patronising. At one end of this scale, John Mitford Bowker, a British settler in South Africa, regretted the disappearance of the Springbok (which he had helped to over-hunt), but thought that Africans “too, as well as the springbok, must give place … Is it just that a few thousand worthless savages are to sit like a nightmare upon a land that would support millions of civilised men happily? Nay, heaven forbids it”. At the liberal end of the scale, the Secretary of State for India Lord Salisbury commented, that “If England was to remain supreme … she must tolerate the political role of Indian princes and of participation by Indians in the administration”, but added later, “… that if the number of well-educated Indians … should increase, the government would face the indecent and embarrassing necessity of closing that avenue to them”.

The Benefits of Colonialism

The violence and racism of colonialism have long been accepted as matters of fact by historians, even if our interpretations of how they came about, how rigid the boundaries of race were, and how they were justified, vary. More conservative historians have long argued that, although regrettable, these features were necessary for the inculcation of modernity. They have stressed the elements of reform that British administrators brought to various societies as they sought to mould them to greater or lesser extents in the image of an imperial Britain that was itself undergoing rapid industrial change. Niall Ferguson in his very popular book and TV series Empire, argued that British colonialism, had introduced certain institutions such as free trade, and legal norms that allowed for higher living standards generally. In fact, Ferguson encouraged the USA to take up the mantle of the ‘White man’s burden’ from an expired British empire and re-occupy countries such as Iraq and Afghanistan to bring order once again. Perhaps the less said about how that turned out the better. Even he, however, did not seek to deny or mitigate the violence and the racism of colonialism in practice.

I want to make one thing clear: in highlighting the violence and the racism intrinsic to the British Empire, specialist historians do not focus solely, as some now allege, on the ‘bad bits’ or the ‘negatives’ of empire. We do not overlook the ‘good bits’ or the ‘benefits’, such as the abolition of slavery or Britain’s determination to ensure that no other nations profited from it once Britain had abolished it. We are very attentive to the reforms introduced against practices considered barbaric, such as sati, in places like India, to educational, infrastructural and health improvements over time.

However, we believe that trying to weigh up what was ‘good’ and ‘bad’ about certain historical episodes or even individuals is a bit primary-school-ish. It is far more important for us to consider who benefitted from certain aspects of colonialism and who did not, and this will of course vary hugely across time and space. Concluding that the Empire was either a net benefit or cost to people in general is meaningless and unverifiable. Often, the same people could both benefit and lose from colonialism’s different aspects at the same time. For instance Adivasi in India might feel liberated from caste oppression from other Hindus by certain British interventions, but subjected to racial oppression by others.

British colonialism was certainly of great benefit to many people. Speaking necessarily here in general terms, it benefitted most Britons, even if unevenly and often indirectly, most of the time; it benefitted Indian merchants who thrived in the conditions created by the East India Company, often at the cost of famine victims; it benefitted certain African leaders, who were able to profit and enhance their power with weapons supplied in return for captives for the European slave trade; it benefitted many around the world who could achieve elevated status by accommodating themselves to British rule.

Innovations that British rulers helped to introduce to many areas, largely for their own and their colonists’ benefit, such as health care, schools and democratic institutions, could be made to work for the benefit of many others once the British had left. It should come as no surprise, though, that the interventions that benefitted some could prove costly to others, and neither should it surprise us that the Empire was administered largely for the benefit of Britons rather than subject peoples. It has been true of all empires throughout history that they exist primarily to serve the purposes of their citizens rather than their conquered subjects.

Why has the discussion of Britain’s colonial past become so controversial?

So what’s happened to generate such controversy over the nature of colonialism just recently? My answer is that the intrinsic characteristics of colonialism – part of its very definition – may have long been known to specialists in the field and may even have been admitted by some of those who nevertheless believed that all the violence, all the coercion and all the racism were necessary to some greater end. But what is crucial is that these characteristics, for the most part, have been ignored or disavowed in much of our public consciousness. Until recently, the most popular accounts of empire were nostalgic and celebratory. They viewed the empire through rose tinted spectacles.

It is the attempt to bring the intrinsic violence and racism of colonialism more to the forefront of public consciousness, especially in the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, that has now sent certain conservative figures on a reactive ‘woke hunt’. Their backlash against greater public understanding of what colonialism in general inevitably entails, and what British colonialism specifically entailed, has sparked an intensity of disagreement and rancour that I’ve not seen in thirty years of researching, teaching, writing about and editing books on the subject. It seems that for many joining in this backlash against greater historical understanding, it is ‘anti-British’ to write about the violence and racism that Britons inflicted on others in the past. There seems to be a misunderstanding that historians like myself are portraying Britons as villains when we talk about their colonial activities.

Let me conclude by addressing this point. Britons, in my and my colleagues’ view, have been neither more saintly nor more devilish as a national group than any other. People of all identities are complex. They tend always to believe that there is justification for their actions even when others see them as inflicting harm. Well-intentioned people are born into and help, sometimes unwittingly, to create systems and social structures that are deeply oppressive. Fae Dussart and I wrote a book, for instance on well-meaning men appointed as Protectors of Aborigines in the Australian colonies, who thought the best way of shielding Aboriginal people from the effects of settler colonialism was to forcibly remove their children into White -run boarding institutions and foster homes.

One does not have to believe that Britons were monsters – or indeed any better or any worse as a nation than any other – to see how the various, diverse forms of colonialism that they imposed, from missionary work through commercial exploitation to invasive settlement, could have terrible effects. A sophisticated historian is able to reveal how even well-intentioned people can produce horrific outcomes and should be able to do so without accusations of being a ‘woke militant’, ‘Far-Leftist’, ‘Marxist’ or ‘anti-British’. Our job remains to tell it like it was, in all its complexity, regardless of how we are misrepresented and sometimes abused in the current culture war.

[…] Britain’s past. Professor of Historical Geography at the University of Sussex, Alan Lester, claims that “one does not have to believe that Britons were monsters – or indeed any better or any […]