Recently I was given the opportunity to do research with the Rusted Lab at Sussex University as a Junior Research Associate. This means I will be continuing the Rusted Lab’s current work measuring the effects of the APOE e4 gene on cognition in mid-aged adults and, hopefully, be able to further our understanding of how and when this gene begins to show detrimental effects on cognition in carriers.

Now for a brief introduction to myself; I am an undergraduate student at Sussex University studying Neuroscience with a pathway in Psychology. I applied, and was (thankfully) accepted, for JRA funding to do research in Jenny’s lab over the summer and have been doing so for 3 weeks now. Since starting my degree in Neuroscience, I have found that the cognitive and behavioural aspects of the science are what I find most interesting, especially in the broad field of memory research. When searching for JRA opportunities, the work being done in the Rusted lab stood out to me; not just because of its contemporary prominence or focus on the genetic basis of cognition (a topic I find very interesting), but also because of the very obvious real world relevance of the research.

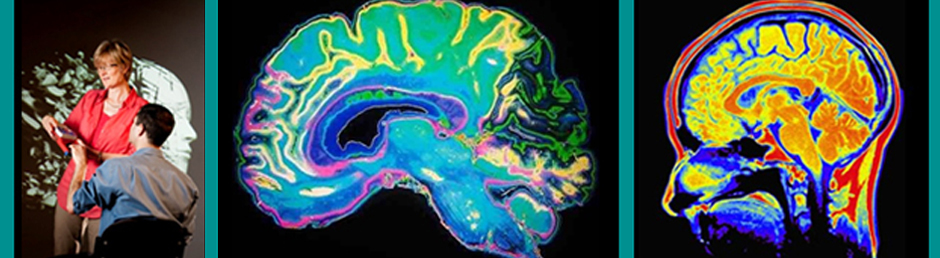

My project will aim to develop a collaborative study between the Rusted Lab at Sussex University and Prof. Graham’s Lab at Cardiff University, to establish a clear cognitive profile in mid-age e4 carriers, and to map these against structural brain changes in a group of mid-age volunteers. Significantly, I will test the Rusted cohort of mid-age volunteers on tasks from each lab (a Prospective Memory (PM) task and Visual Paired-Comparison (VPC) task). Secondly, with advanced image analysis support from the CUBRIC facility in Cardiff, I will cross reference cognitive effects against the archived structural imaging data for this group. This will hopefully add to our understanding of age related cognitive changes in e4 carriers as well as differences in mid-age e4 and e3 (the population norm) carriers.

As it’s early days, I don’t yet have any earth-shattering results to share, but I am very excited to see what is possible in APOE research and to continue learning a lot about the correlation of this gene and Alzheimer’s-type dementia.

Recent Comments