Each year on May 12th, the Mass Observation Archive invites people from across the UK to submit a diary account of their day. This event first took place on 12th May 1937, the day of King George VI’s coronation, and has now become an annual tradition – providing a snapshot of what is happening in people’s everyday lives across the country.

This year, on Tuesday 12th May 2015, the Mass Observation Archive would like to invite children and young people to take part in this event, and to share a day in their life. In the video below, a group of young people and their parents explain why they think you should take record your day on May 12th.

Traditionally the Mass Observation Archive has invited people to record a written diary of their day. On May 12th this year, children and young people are invited to record a day in their life in whatever way they like – using sound, video, photographs, pictures, or even a written diary if you would prefer. Below are a few examples of day diaries in video form recorded by young people for the Mass Observation Archive.

In the diary of your day, you might want to include important things such as: what you do, who you meet, what you talk about, what you eat and drink, the places you visit, the things you read, see and hear around you – and, of course, what you yourself think.

Diaries should be in electronic form as email attachments (to moa@sussex.ac.uk) or alternatively you can bring them along to a special ‘Your Life in a Day’ event at the Mass Observation Archive Building – The Keep – on Saturday 23rd May (see below).

In your diary, you should try and avoid having information or images that are too personal or identifying. As part of a new ‘Everyday Childhoods’ collection at the Mass Observation Archive, these diaries will be read and used for research and teaching, so try to avoid including anything that may identify you or others.

So that your diary can be added to the rest of the Archive for the future, you’ll need to include the statement below at the end of your diary. If you don’t attach this statement, Mass Observation won’t be able to keep your diary or make it part of the Archive:

“I donate my 12th May diary to the Mass Observation Archive. I consent to it being made publicly available as part of the Archive and assign my copyright in the diary to the Mass Observation Archive Trustees so that it can be reproduced in full or in part on websites, in publications and in broadcasts as approved by the Mass Observation Trustees. I agree to the Mass Observation Archive assuming the role of Data Controller and the Archive will be responsible for the collection and processing of personal data and ensuring that such data complies with the DPA.”

You can find out more information about submitting your diary at: http://www.massobs.org.uk/12may

On Saturday 23rd May (10am-1pm) at the Mass Observation Archive building (The Keep), a free family workshop will be held where you can learn more about recording and archiving a record of your day. The event will include members of the Everyday Childhoods project, sharing examples from our ‘day in a life’ studies, as well as Cameraheads from the Youth Photography Project.

Visit the Brighton Fringe Festival webpage for more details:

Information on how to find The Keep can be found here: http://www.thekeep.info/visit_us/getting-here/

May 12th is a fantastic opportunity for children and young people to document a day in their life and to contribute to a historical record of everyday life dating back to 1937. You can help by encouraging them to take part and by providing opportunities to record different parts of their day. If you work in a school, club or youth organisation, why not make May 12th an activity all of the children and young people you work with can take part in? May 12th is a unique chance for children and young people to show what an ordinary (or extraordinary) day in their life looks like.

Liam Berriman May 3rd, 2015

Posted In: Blog

Dr Sara Bragg

A recent University of Brighton initiative, the Research Leadership Programme, involves participants shadowing a ‘research leader’ from a different institution for a day. I went to meet Matt Arnold, head of research at Face Group in London; its website describes it as ‘a global strategic insight agency’ delivering ‘socially intelligent research by combining qualitative insight, real-time data and smart thinking’.

I expected the Fatboy beanbags in the reception area on my arrival, but I was more surprised to be shown into a starkly-lit basement, where Matt and a colleague were huddled over a conference call with a client. I gained a clear impression of the speed and pace of the corporate world, observing Matt helping colleagues work out the logistics of designing and delivering research in different countries and even continents within the space of a few days. I wondered how compatible such long hours would be with ‘work-life balance’, and how far this is a young (single/childfree?) person’s world…

I was equally fascinated by their research methods, and here there were immediate similarities with ‘innovative’ social science approaches. For instance, Face Group has developed an app that prompts research participants to generate data such as a diary, photos, film, notes. As in the social sciences, ‘traditional’ focus groups are increasingly seen as limited, capturing conscious, post-hoc rationalised reconstructions of behaviour rather than contextualised feelings and actions in the moment.

Face Group also has its own ‘social media listening’ service, distinguished by a sophisticated natural language processing capacity that can help identify different kinds of consumer and what they are ‘saying’ across social media platforms. Having recently experimented with using free social media analysis packages such as Node XL to understand teachers’ professional learning networks, I am only too aware of their limitation and the desirability of more powerful tools such as these.

Similarly, ‘co-creation’ and ‘co-research’ are increasingly popular and widespread terms. Face Group can lay claim to some ownership of the concept, having developed specific, multi-layered, recursive research processes under this rubric. For instance, developing new personal care products might bring together the client with the ad agency, design agency, R&D and experts from Face Group’s own ‘black book’ (such as, a hairdresser with their own exclusive product range, fashion specialists, a sous-chef who understands smell and taste). Consumers would be carefully recruited – completing questionnaires, auditions and set tasks – to ensure they were articulate, sociable and represented ‘100%’ of different target audiences. Over the course of an intensive five-day programme, experts would give presentations; consumers provide information about themselves, how they think, what they do, their lifestyle and attitudes; diverse teams would be assembled; new product ideas would be developed with R&D keeping ‘in the parameters of what is realistic’ and using creative techniques where participants build on each others’ ideas; an artist would be on hand to capture the affective texture of the day… culminating in outcomes matching the objectives set out at the beginning.

Or to give another example, a project to develop new smart technologies involved intensive mini-ethnographies, spending a few hours with research participants at work and at home, to understand their needs and technological dilemmas in situ. Diverse findings were then grouped and condensed into vivid ‘vignettes’ when presenting findings to the client. At a procedural level, again, there are many resonances with social science methods, right down to the presence of visual artists at conferences. Certainly, the Face 2 Face project in which I have been involved has been discussing similar approaches.

Social science is often concerned with marginalized social groups, who (being poorer) are necessarily of less interest from a marketing point of view. Our audiences may also be less keen on our findings, however well-grounded, than a client seeking knowledge of a market: in education, for example, politicians consistently ignore evidence about the negative consequences of ability-labelling and streaming practices. Education researchers often speak in terms of loftier goals such as ‘social justice’. Could this be broken down into achievable goals and steps and a programme for delivering it developed through co-research? What is the place of data analysis – would a social scientist make very different use of the kinds of data gathered by market research? At a conference of the Centre for Research into Economic and Social Change (CRESC) I attended some years ago, some fascinating papers were doing just that with survey data from the 1950s. It would be very interesting to develop further dialogues about these issues across sectors, data, and interests.

Liam Berriman February 20th, 2015

Posted In: Blog

Tags: commercial research, day in a life, market research, methods, research, Sara Bragg

Dr Liam Berriman

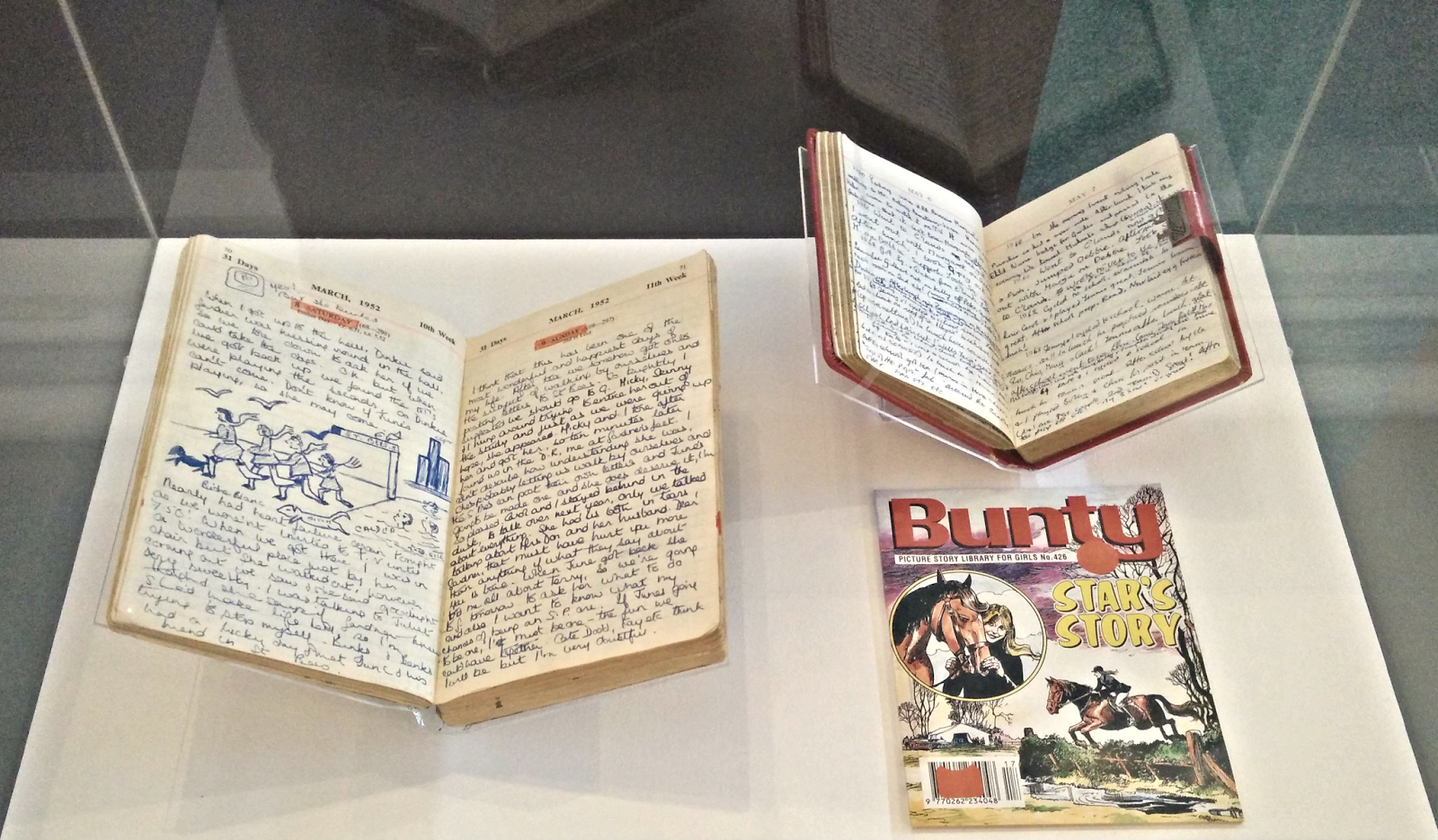

This summer the Museum of Childhood (MoC) hosted an exhibition on children and teenager’s diaries, with examples ranging from a 15-year-old teenage girl writing in 1947 about her turbulent love life, to a teenage colliery apprentice writing in 1838 about the death of a fellow miner. These diaries form part of a larger collection called ‘The Great Diary Project’ currently housed at the Bishopsgate Institute, incorporating both children’s and adults’ diaries from across the 19th and 20th centuries. According to The Great Diary Project website, the aim of the collection is to attempt to ‘rescue’ as many diaries as possible in order to preserve the highly personal accounts of everyday that they contain.

In this short piece I share some reflections on visiting this exhibition by linking together a number of themes I have been thinking through this past year. In particular, the (historical) materiality of children’s media practices, and issues around audience, privacy and authorship.

Viewing the diaries arranged in glass cases, it’s hard not to be st ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.

ruck by their diverse material forms. From pocket-sized, leather-bound journals filled with minute handwriting, to sheets of ruled paper tied together and covered with black biro and carefully glued magazine clippings. The exhibition offered a carefully curated selection of diaries from as far back as 1838 and as recent as the mid-90s. Placed in juxtaposition, the diaries made visible a variety of trends in handwriting, ink and paper qualities, the use of visual images and collaging and, of course, the issues of value and significance in each of the writers’ lives.

In a recent article, Liz Moor and Emma Uprichard (2014) describe the significance of the materiality of archival objects. They propose we need to pay attention to, “how the material qualities of paper and type/script make the research process a sensory and emotive experience” (Moor and Uprichard, 2014: 6.1). By narrowly focusing on the ‘content’ of a diary or archival documents, they suggest we may miss “the sensuous ‘cues’ and ‘hints’ offered by the archive’s materiality” (2014: 1.2).

In an essay for the London R eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.

eview of Books, Mark Ford similarly asserts the importance of experiencing the poems of Emily Dickinson in their original material form. According to Ford, Dickinson regularly wrote on scraps of paper and envelopes, fashioning her poems around their material form. He describes how Dickinson “razored or scissored the envelopes in a deliberative manner” (Ford, 2014) as a way of crafting the poem into a material artefact.

Individually, the diaries exhibited at the MoC offer a fleeting material and biographical trace of their authors, offering just a glimpse of the values, concerns, and aspirations that they chose to inscribe on paper at a particular moment. What remains is a material artefact, now spatially and historically separated from its author, yet still retaining the affective traces of the cares and concerns that they chose to impart on its pages.

All too often we read past media through a contemporary lens, judging their modalities and affordances by our own relationships with digital and online media in the present. The diary, in particular, has been subject to modern comparisons with online blogging and video diaries – both of which have been described as present-day ‘confessional’ devices. Comparisons between these different forms of cultural practice are, however, highly problematic. Rather than simply seeing them as analogue/digital equivalents, each cultural practice needs to be seen as shaped through a distinct set of values and technological modalities. I briefly focus here on the significance of privacy and audiences for the diarists.

In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.

In the semi-biographical novel The Boy in the Book, Nathan Penlington recounts his attempts to locate the author of a childhood diary he finds amongst a set of second-hand Choose Your Own Adventure books. Penlington feels that he and the diary’s author shared a similarly difficult childhood and he feels compelled to discover how the diarist’s life has unfolded. During his quest, Penlington is troubled by a number of ethical questions, in particular: how the diarist will feel about the diary being ‘discovered’ and read by another person, and whether they will want to be re-confronted with the memories it contains.

A point of commonality across the diaries on display at the MoC was their often highly personal disclosure of thoughts and events significant to the writers’ lives. Looking through them I often felt an uneasy sense of prying, despite the often substantial ‘historical distance’. Occasionally the diaries were written in a way that appeared mindful of potentially uninvited and unwanted audiences. For example, one of the diaries was transcribed in an elaborate code devised by the author as a way of deterring would-be snoopers, whilst another diarist’s reference to ‘getting rabbit food’ was potentially used to hide a smoking habit. In these instances privacy might be seen as a highly localised encounter, with information specifically concealed from inquisitive friends, parents or siblings.

Our contemporary standpoint on privacy positions all forms of content production as potentially highly ‘risky’, even when not intended for wider audiences. During the recent spate of celebrity photo leaks the EU digital commissioner Günther Oettinger placed part of the blame on the victims for having been ‘stupid enough’ to create the images. Our contemporary networked world is one in which privacy is positioned as primarily the responsibility of the individual, and where personal content can rapidly circulate through wider audiences without warning or consent. Consequently, contemporary teenagers are increasingly burdened with the fear of spoiling reputations through the content they produce. This is not to say that the diarists displayed at the MoC did not have their own sets of concerns around privacy and audience, but it is nonetheless important to acknowledge the fundamental differences in the way that such concerns are actualised and played out.

Further Reading

Ford, M. (2014). ‘Pomenvylopes’, The London Review of Books, 36(12), pp. 23-28.

Franks, A. ([1952] 2011). The Diary of a Young Girl. London: Penguin.

Moor, L. & Uprichard, E. (2014). ‘The Materiality of Method: The Case of the Mass Observation Archive’, Sociological Research Online, 19(3), 10.

Penlington, N. (2014). The Boy in the Book. London: Headline.

Liam Berriman November 19th, 2014

Posted In: Blog

Tags: archive, curation, diaries, everyday, Liam Berriman, materiality, museum of childhood