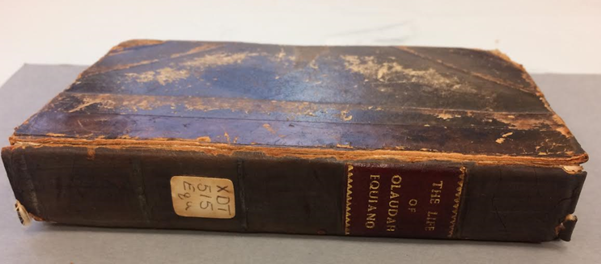

Rosey Pool and the case of the damaged Equiano; or a book made safe and a treasure revealed.

With new software becoming available all the time, could AI text-to-image tools redefine how we create and use images at work? Join our Systems Librarian, Tim, as he uses software that is freely available to staff to explore creating AI-generated…

From translating videos into multiple languages effortlessly to creating lifelike avatars and cloning voices, AI is reshaping the way we communicate through videos. Join our Systems Librarian, Tim, on a journey through the cutting-edge technology that’s shaping the future of…

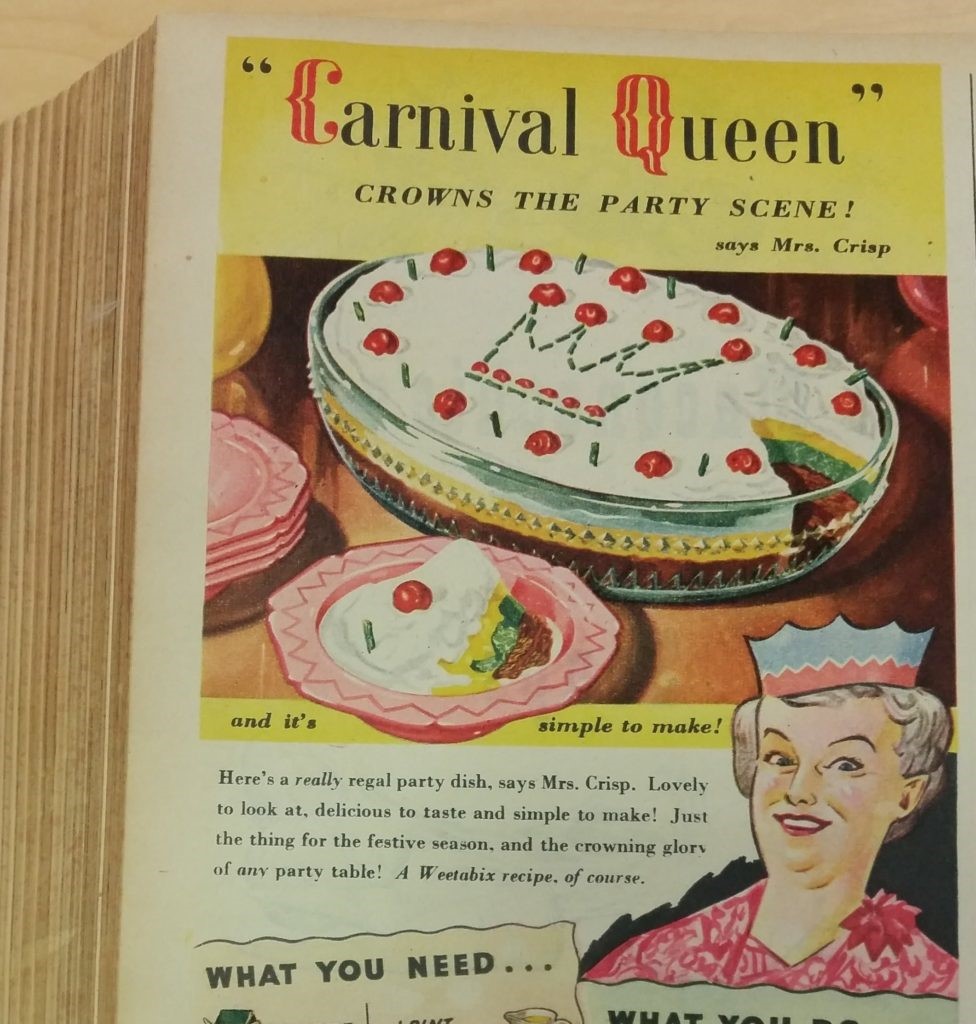

By Rose Lock Women’s magazines. Trivial, eh? Just a collection of inconsequential articles on how to keep your man happy, patterns for knitted shorts, vile make-do-type recipes, and adverts for lipsticks and washing powder. Well, yes, all of these things…

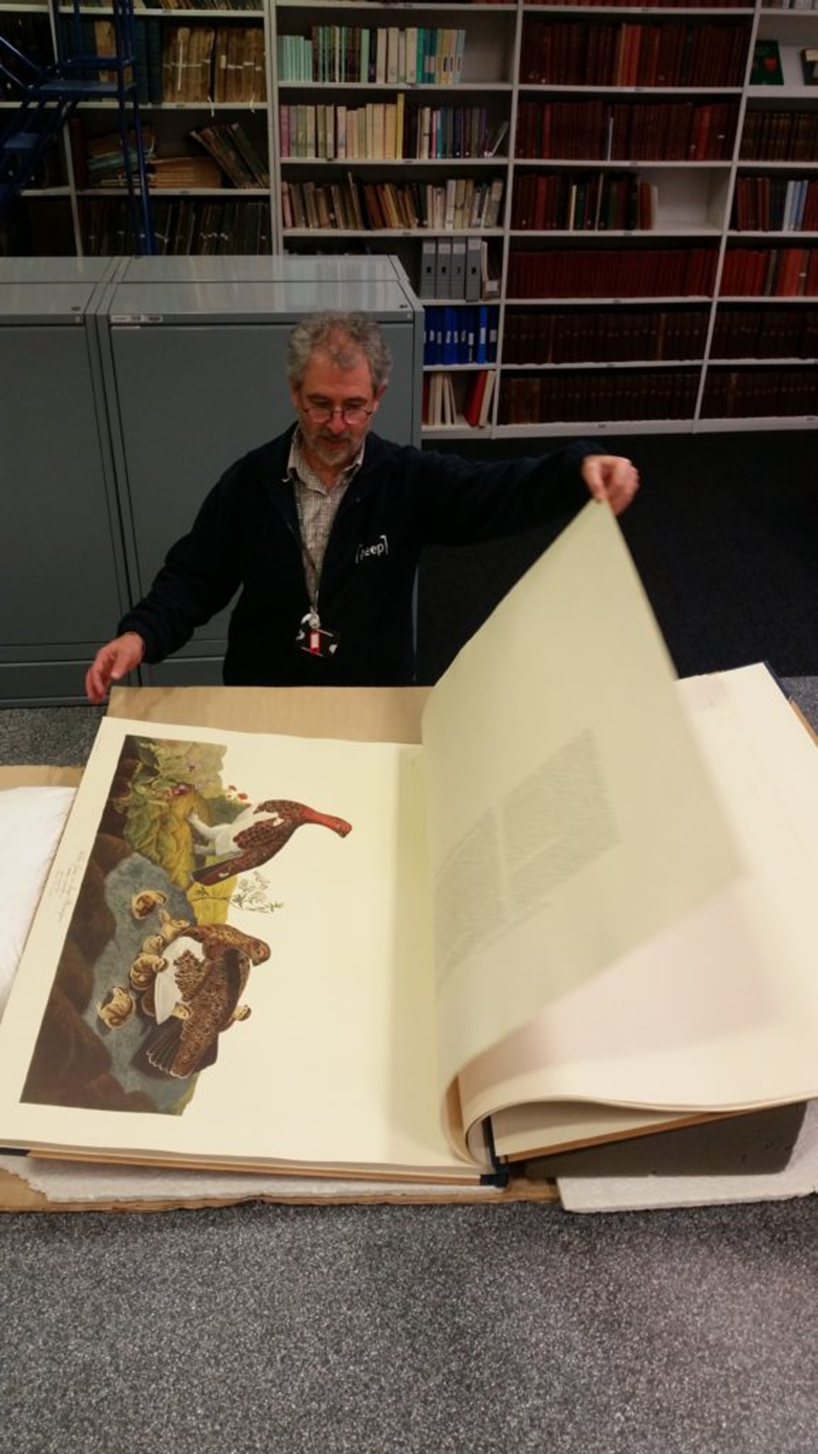

We are lucky at the University of Sussex Special Collections to have a number of fabulous and varied rare book collections, which are now part of the wonderful collections held at The Keep. As well as individual researchers ordering in our reading room, academics from Sussex and other universities use the books to teach their courses, running seminars in our education rooms where the students can get first-hand experience of handling rare volumes.

by Helena MacCormack

As someone who has studied performing arts for years, I understand the unique journey that drama students embark upon. Theatre is a vibrant, living art form where practice and creativity take centre stage. However, there is a misconception that theatre students exist in opposition to academia due to the practical nature of their degrees. While practical work is at the core of theatre studies, academic research plays a crucial role in shaping your perspective as a theatre practitioner. This post marks the first of a series which will detail 5 ways in which the Library’s resources can provide academic grounding to your theatre studies, with plenty of recommendations.