The problem with making the history of the British empire a weapon in a divisive culture war is its omission of empathy.

Conservatives, exemplified by The Telegraph’s editorial line, feel that radical activists are determined to see Empire as an evil project, regardless of the sensitivities of Britons brought up to believe in their ancestors’ good intentions. Tearing down statues, reinterpreting National Trust properties, browbeating museum visitors with critical content, and lecturing White Britons on their inherited racism are all seen as acts which lack any sympathy or understanding for the majority of Britons. They are especially triggered when national heroes like Winston Churchill are challenged as racists, and when the iconography of an innocent and quintessentially English countryside, graced by stately mansions and landscaped gardens, is interpreted as, in part, the product of slave ownership and racial exploitation (even though they may acknowledge the engrained exploitation of British workers with just a shrug of the shoulders).

White friends of mine have argued that, if only the assaults on their long held beliefs and identities were not so vehement, if only those drawing attention to the violent realities of Empire were more reasonable in attempting to persuade them – if only they showed more empathy – then they would be more inclined to listen.

The fact that much of the government’s discussion of racial disparities is conditioned by the defence that there’s no structural racism to see here, helps to persuade many of my White friends that they are being unfairly maligned for the sins of their ancestors.

Those reacting against a supposed ‘woke’ assault on history are enraged that empathy seems to be directed solely towards Empire’s victims, with no appreciation of the good intentions of British colonisers. One of Nigel Biggar’s constant refrains, demonstrated in his critique of Dan Hicks’ Brutish Museum is that Hicks shows no empathy for the British who invaded Benin, burned its capital and stole its treasures. Hicks seems to empathise only with the expedition’s victims, and neither with the British invaders themselves nor the enslaved victims of Benin’s own ruler. Biggar accuses Hicks of “an ethical schizophrenia—on the one hand morally neutral and indulgent toward non-Western, African culture, on the other hand morally absolutist and unforgiving toward Western, British culture”. Biggar goes on to detail the accusations made by expedition members that there was widespread and revolting evidence of the kingdom’s practice of human sacrifice.

A project that I was involved with providing a new interpretation board for the statue of the Victorian army general Redvers Buller in Exeter tried to pay attention to this conservative feeling of a lack of empathy among Empire’s new critics – a feeling that has been mobilised so effectively by the culture warriors of the Telegraph, Mail and Express. We tried to proceed through dialogue and engagement with all sides in what has become a highly charged debate over the fate of the statue.

However, what has become clear in the course of this and other projects of late is that it is also incumbent on all Britons today to empathise with those now seeking to challenge our dominant understanding of the colonial past.

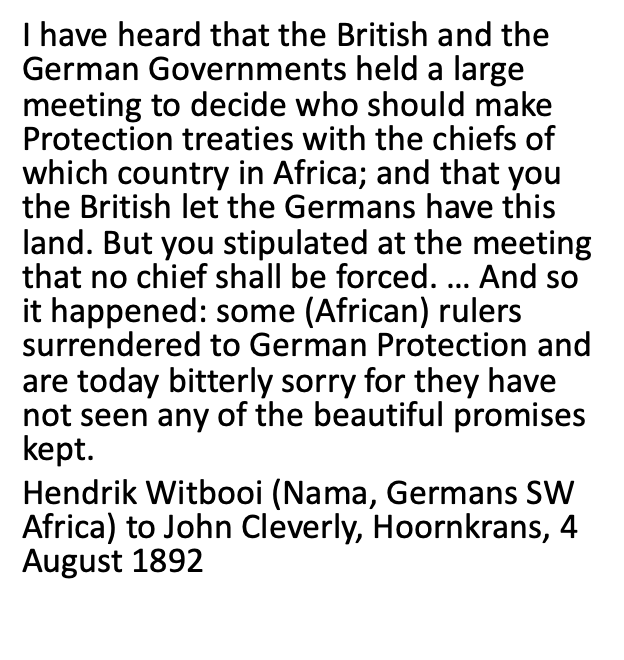

There were many people of colour around the world who, once rendered British subjects by conquest, adapted and even prospered from alliances and negotiations with their new rulers. Indian merchant families especially collaborated with East India Company and other investors and sought to share in the education offered by the British even as they were denied a share in central governance. As one would expect during any radical reconfiguration of power relations, certain groups enhanced their power over traditional rivals by allying with British rulers and accepting what limited degrees of autonomy they could negotiate with them in return. During the Scramble for Africa especially, some African and Pacific leaders saw British rule as the lesser of two evils when confronted with a sudden French, Belgian or German determination to catch up and match Britain’s exploitation of colonies. For Hendrick Witbooi of the Nama, for instance, a British protectorate would have been a far better fate than German colonisation.

But we delude ourselves spectacularly if we think that a fond appreciation of British colonisation was the norm among subjugated peoples. Millions of people of colour were killed trying to resist the British takeover of their lands. In Ruling the World we examined three years of the nineteenth century closely and estimated that in the wars of conquest fought in and around those years alone (including two Opium Wars in China, two invasions of Afghanistan, the Indian Uprising, and a series of imperial wars to confederate southern Africa) over a million died, although it is difficult to be precise because the deaths of people of colour were not recorded in the same way that White people’s deaths were. Millions more died in famines that the British colonial governments could and likely would have done far more to prevent had the victims been White (although their semi-racialised brand of Whiteness did not protect Catholic Irish subjects from mass starvation during the Great Famine). Sixty five so-called “small wars” were fought by late Victorian armies either to annex new territory or to punish African, Asian and Indigenous societies which resisted British demands. Scorched Earth tactics inlcuding the burning of entire villages were used regulalry. This is not to mention the disastrous long term effects of British attempts to govern Iraq, Palestine, Afghanistan and other zones in Britons’ rather than local peoples’ interests, nor the attempts to cling to influence after World War II in Egypt, Aden, Malaya and Kenya.

Well after the abolition of slavery, colonial laws ensured that people of colour’s labour was supplied to White employers freely, or as cheaply as possible, and colonial laws discriminated between coloniser and colonised whatever the British government itself claimed of their non-racialism. With formal empire on the wane, many more British subjects of colour migrated, invited, to Britain to become citizens, and found themselves rejected as equals. The ideologies of racial difference that had sustained colonial rule out there in the empire for so long were now applied more systematically against people of colour in Britain as Enoch Powell and others feared national disintegration from their presence and ever more racially restrictive immigration laws were passed.

Is it too much to expect the majority of White Britons to empathise with most Black Britons over these aspects of our national story? To the defence that things have changed, that there is a progressive move away from overt racism, and that Britain is less racist than other European countries, I would urge the ‘anti-woke’ to examine two things.

First, how such progress has come about. From their victimisation in the 1919 race riots through the Bristol bus boycotts, the New Cross fire, the Stephen Lawrence campaign and other instances, it has been the mobilisation primarily of Black Britons against racism which has spurred official enquiry and legal reform. This progress too is a result of the empire. Britain’s vibrant communities of Black activists, themselves a product of late- and post-imperial migration, and their white allies, have been responsible for what progress there has been. It is the European countries that are overwhelmingly White which still tend to espouse the racial ideas that were disseminated within and beyond the British Empire most vigorously. Secondly, there is still a long way to go to address the structural inequalities that racial discrimination over centuries, and across the world, has seeded in the UK itself. One need only look at the Office for National Statistics figures on ethnic and racial disparity or the painful and ongoing Windrush scandal to understand this.

Culture warrior scholars like Nigel Biggar could certainly do with showing a little more empathy. He may criticise Hicks for having little sympathy for Victorian Englishmen, but his own account of the Benin Expedition derives solely from the racist pretexts that these men provided for their assault. He makes no attempt to engage with historians who have examined the expedition from the perspective of its African victims. At the very least, some more engagement with historians might have allowed him to contextualise the horrors that the British expedition members reported. This does not entail excusing the evidence of human sacrifice (explained by experts on the region as the ritual punishment of criminals and those accused of witchcraft rather than arbitrary and mass killing), but it might entail an appreciation that perhaps the sacking and looting of a city and the killing of those who resisted might be seen as a fairly extreme response to what was essentially a trade dispute.

Biggar’s other claim to justification for the expedition was the “massacre” of a “a diplomatic mission, whose nine White members, led by Acting Consul James Phillips, had been deliberately unarmed, “apart from revolvers”. In fact Phillips had written to the Foreign Office before his departure for Benin that he intended “to depose and remove the King of Benin and to establish a native council in his place”. It was not just nine “unarmed” white men (if we can just dismiss their revolvers) on the mission. Phillips reported that he had “a sufficient armed Force, consisting of 250 troops, two seven pounder guns, 1 Maxim, and 1 rocket apparatus of the N.C.PE, and a detachment of Lagos Hausas 150 strong.” The postscript was appended: “I would add that I have reason to hope that sufficient ivory may be found in the King’s house to pay the expenses in removing the king from his stool” (Evo Ekpo, The Dialects of Definitions: “Massacre” and “sack” in the history of the Punitive Expedition, African Arts, 30, 3, Summer 1997, 34-5; James D. Graham, The Slave Trade, Depopulation and Human Sacrifice in Benin History: The general approach, Cahiers d’Études Africaines , 5, 18, 1965, 317-334).

If it is incumbent on activists to attend to the sensitivities of those who cherish imperial era statues and legitimations, then perhaps it is even more incumbent on those of us brought up to cherish these things to listen to, and empathise with, those whose heritage includes mass killing, dispossession, oppression, and exploitation by White Britons engaged in imperial projects. Can we not empathise enough with most Black Britons today to see how commemorating men who enslaved, killed, conquered and exploited their ancestors might not be conducive to a “shared national story”, as History Reclaimed puts it?

I know I’m a few years late, but this is an excellent article. I think that the dismissal of Empire by categorising it as “normal in its context” can definitely be quite reductionist. If one views colonialism solely through a British perspective, you haven’t grasped what the Empire really entailed because you’re erasing the perspectives of the millions colonised by the British Empire. Britain severely stunted the countries it occupied, which isn’t something to be proud of even if the British viewed their Imperialism as “noble” and didn’t recognise its flaws.