The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History has recently published my Extended Critique of Nigel Biggar’s book Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning. Prof. Biggar’s Reply was published alongside it.

Like his history of colonialism, Biggar’s reply has unorthodox features, some of which I will engage with, others I will not.

Balance: Page 276

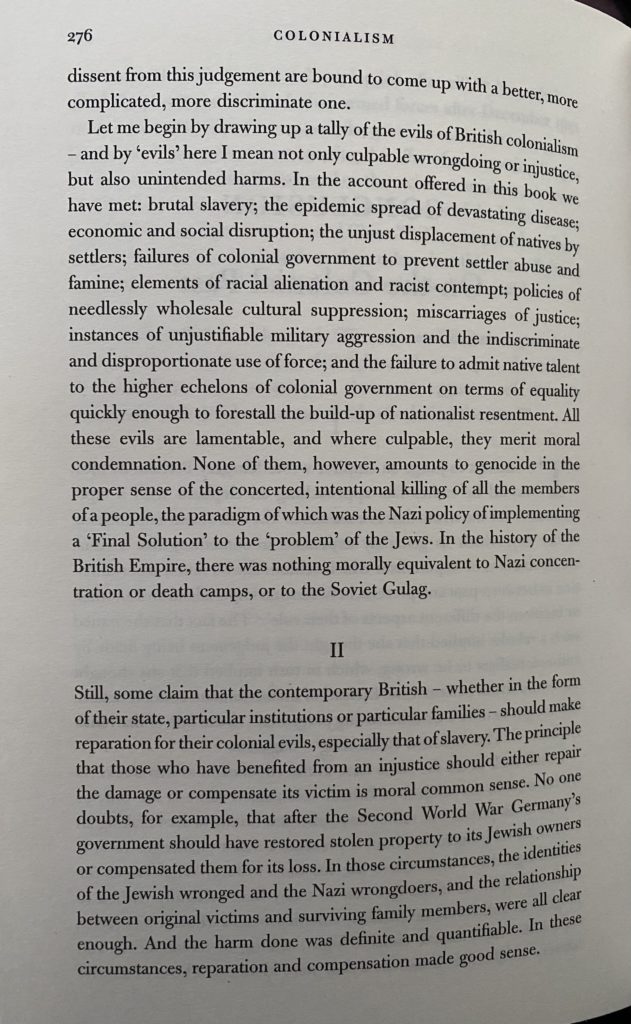

Prof Biggar seeks to respond to each of my nine examples of his misuse of data. He does not explain why his errors, some of which he admits to, others not, all tend in the same direction: towards the justification and mitigation of colonialism’s violence and racism. He complains that my article fails to reflect his balanced approach to colonialism, noting that he is “candid about the evils and injustices of the Empire and provide[s] a summary on page 276”. Later, he claims that I “need only to have read 276 to find a summary of the different kinds of evil and injustice for which I hold British imperialists and colonialist either responsible or culpable”. This page would have to be very weighty to balance the other 428 pages of substantive text and footnotes generally justifying colonialism. Yet, p. 276 seems to be aimed at providing mitigation rather than analysis. We are instructed that, for all its faults, the British Empire was not as bad as Nazi Germany’s death camps or the Soviet Union’s Gulags.

Racism

Readers will judge for themselves whether the claim that Africans lack compassion compared to Europeans is not racist, as long as it is environmental rather than biological determinism that underpins that claim. In his response Biggar doubles down on his claim that only biological determinism counts as racism: “it is perfectly possible to regard certain current features of another person’s culture as inferior in certain respects, and still to accord that person a basic human respect, which includes the view that he or she has the same human potential to learn and grow as anyone else. Such an attitude, in my view, is not racist.” Let me quote from Stuart Hall on the relationship between biological and cultural racism: “so called biological racism has never been separated from cultural inferiorisation. Blackness always functioned as a sign that people of African decent are (a) closer to nature and therefore (b) more likely for that reason to be lazy, indolent, lacking in higher intellectual faculties, driven by emotion 8 not reason, oversexualised, prone to violence, etc, etc… The two logics have always been intertwined, ever since the beginning … There has never been one or other of these logics in the structure of social exclusion. It is of course true that in different historical contexts one or other of these two logics (biological racism or cultural inferiorisation) has often been foregrounded and this has had different effects in different historical communities. Leading to the necessity of our now speaking of racisms in the plural and bringing biological racism and cultural inferiorisation together in an expanded conception of what racialisation is about in the modern world”.

Political Positioning

Biggar has completely ignored the statement of my own political position and done exactly what I sought to guard against when including it: allege that I am driven as much by Left wing politics in my approach to history as he is by his Right wing views. He makes no effort to refute my analysis of his own political motivations. To suggest, without any basis whatsoever, that my longstanding professional involvement in colonial history is as politically driven as his own, which he admits dates only from his political decision to resist the Rhodes Must Fall campaign, is simply a deflection from the analysis of his book.

Culture Warrior or Colonial Analyst?

Nothing proves Biggar’s immersion in the tactics of the culture war, over and above any interest in debating colonialism, better than his second deflection. This is to the unrelated controversy concerning Prof Kathleen Stock.

In my review article, I located Biggar in a culture war context because it determines entirely his book’s approach to colonial history. Biggar chooses not to reject that association but rather to attempt ‘retaliation’ against the reviewer. He seeks to connect me to a different ‘front’ in the culture war – one which has nothing to do with the book’s purported subject or my comments on it.

His only reasoning for a connection is that fact that Prof Stock and I worked at the same university. It seems hypocritical of Biggar to then rail against another historian for apparently associating him with Thomas Carlyle based on their birthplaces and with Richard Dearlove based on their shared school. In attempting tit-for-tat rather than refuting the point I was making, Biggar only demonstrates that it is indeed political contestation rather than scholarly debate that drives his intervention.

Victor Orbán

Having first tried to smear me by association with the activists who sought Prof Stock’s dismissal, Biggar asks “What does the fact that Viktor Orbán was interviewed as an inspirational figure during the 2020 National Conservatism conference in the U.S. say about me? Nothing at all. So why report it?” The answer is obvious. With many conferences one would not expect any political alignment between participants. The National Conservatism conference is not just any conference. As has been widely reported, it is sponsored by the Trump-aligned far right in the USA and it exists to propagate its political ideology of National Conservatism. All of its speakers are chosen because they align with that shared political doctrine. Furthermore, Biggar is linked directly with Orbán’s government. He was a keynote speaker at the Brussels launch of Orbán’s Mathias Corvinus Collegium (MCC), a body created to ‘educate’ (one might argue, indoctrinate) the next generation of Hungarians with exclusive nationalist ideology. Its chair of trustees is Orbán’s brother, Dr Balázs Orbán. I drew attention to Biggar’s association with the National Conservative movement because its political doctrine determines his arguments in the book.

Whereas I associate Biggar with the doctrines that drive his analysis of colonialism; he tries to associate me with all sorts of things that have nothing to do with that phenomenon, and with no evidence for any association in the first place.

Prof Biggar’s Contribution to the Launch of the Orbán government’s National Conservative ‘educational’ project

Straw Men

Biggar complains about my and Jon Wilson’s observation that he constructs “anticolonial” straw men against whom to argue. Again he slants his defence towards the ad hominem, suggesting that this might be because we are “miffed” that he has not paid attention to our own work. “If so”, he continues, “the reason is simple: the likes of Hilary Beckles, Dan Hicks, and Caroline Elkins have far more influence on the wider, public world than they do.”

However, Biggar’s book does not just condemn any supposed excesses of these more popular historians. It is a history of empire of its own, upon which Biggar then casts moral judgement. In constructing that history, he ignores not just the work of Jon Wilson and myself, but an enormous scholarship on that empire in general, produced by hundreds of colleagues around the world. This is poor scholarly practice in any discipline. The only explanation that I can offer is that this scholarship includes insights of an empirical nature that cannot simply be dismissed as politically motivated, but which do not accord with Biggar’s political preferences.

Tasmanian Genocide

On the Tasmanian genocide, Biggar succeeds in reinforcing my point. He states that “historians such as Henry Reynolds and Dirk Moses reject [the use of the concept of ‘genocide’ to describe what happened in Tasmania in the 1820s-30s] for the same reasons I do … If there is some particular text that would add an important philosophical or legal contribution to my discussion of genocide, Professor Lester does not identify it.” I would be happy to supply Biggar with a reading list but my first suggestion is that he read in full the sources that he already cites.

While he complicates the use of the word “genocide”, Dirk Moses does not reject the concept in Tasmania at all. Rather he identifies “genocidal processes” there, but also and more particularly in Queensland, which Biggar ignores along with most other violent colonial frontiers. Dirk Moses tells me that the claim of Biggar’s that he is in agreement with his work is “totally disingenuous”. Moses arranged the publication of Raphael Lemkin’s unpublished essay on genocide in Tasmania precisely to show how the concept applied there. Lemkin was the originator of the legal concept of genocide. Biggar could also profit from reading the full article by Ann Curthoys, which he again cites without apparently being familiar with its contents. As I pointed out, Curthoys concludes clearly that genocide applies to Tasmania.

Conclusion

Prof. Biggar complains that I have nothing positive to say about his book. This is correct. I have published reviews of over 40 academic books on colonialism. I have had analytical points of difference with some of their authors, but I have always made a point of emphasising the things that we can learn from reading their analyses. Even if their interpretations differed wildly, all of these scholars were intent on understanding and explaining the actors and actions involved in colonialism. They developed and adapted their arguments in response to a wide range of primary and secondary sources. None was driven from the start to tell a highly selective story purely in the interests of a contemporary political project.

Uncited in Nigel Biggar’s “Colonialism: a Moral Reckoning”. there is more wisdom and truth contained in Desmond Tutu’s famous comment on colonialism –“When the missionaries came to Africa they had the Bible and we had the land. They said, ‘Let us pray’. We closed our eyes and when we opened them we had the Bible and they had the land”– than in all 480 pages of Biggar’s self-regarding and self-justifying magnum opus.

A cursory look into the index of “Colonialism” reveals other glaring gaps. No mention of British-Canadian anthropologist Ronald Wright’s “Stolen Continents” and other writings. No mention of the now infamous “residential schools” in Canada, an abomination instituted to “take the Indian out of fhe child ” by Canada’s first prime minister, John A. Macdonald. Nor any mention in the bibliography of Edward W. Said’s “Culture and Imperialism”.

Such glaring omissions make Biggar’s book suspect right off the bat.

To argue that nothing about one culture can be superior to that of another culture seems absurd. Take a culture where corruption of public officials is commonplace and compare it another where corruption is rare and looked down upon. What about a racist culture versus a non-racist culture? At least on the aspect of racism, wouldn’t the non-racist culture be better? Dr. Lester seems to use calls of racism to avoid engaging in any moral comparison that would make the British Empire look good.

Thanks for the comment Ethel,

I’d encourage you to reflect on what you actually mean by ‘one culture’ and ‘another culture’. Where exactly do you draw your boundaries between these ‘cultures’? I ask this because, ever since the end of WWII when the full horrors of the outcomes of the Nazis’ racial thought came to be appreciated and condemned in the West, it has been socially unacceptable to base ideas of group superiority or inferiority on biological notions of ‘race’, yet there has been considerable slippage between the concept of group ‘culture’ and ‘race’. That slippage tends to happen whenever ‘culture’ is used in the way you are using it, to establish the superiority of certain people over others. The notion of White European people’s supremacy over other peoples has been the consistent outcome.

It is as difficult to establish discrete boundaries between ‘one culture’ and another as it is biological boundaries between one ‘race’ and another. Both are products of a kind of wishful thinking about the range of human differences and one’s own group’s position within them. Can you define a British culture, for example, that’s discrete? What attributes does European ‘culture’ have that are unique to itself? Is something like the example you cite, corruption, really more a property of certain ‘cultures’ and not others? Is something like the granting of hospitality to strangers peculiar to some cultures and not others? If one practice, such as hospitality to strangers is more prevalent in culture A, but corruption is less prevalent in culture B, which of them qualifies as the superior culture? Once you have established that, say, A is the superior culture, does it then justify their invasion and occupation of B’s lands, the use of B’s resources and B’s labour for A’s people, on the grounds that you are helping B to adjust to A’s norms?

Is there a possibility that different cultural traditions, vary within any given society as much as they do between societies, that societies can be hybrid, containing a kaleidoscope of different cultural practices and beliefs, that they can change without violent conquest being the impetus? Can people learn different ways of doing things, different beliefs across cultures? Can a single ‘culture’ like Britain’s, be more or less corrupt for example at different times?

When you think of someone who does not share whatever bundle of attributes you see as your ‘culture’, does the image that pops up in your mind tend to be one of a person of a different ‘race’ or a different religion, rather than a White British person like me? Are you really just substituting the idea of cultural difference for ideas of racial difference, because it’s more acceptable to think in hierarchical terms that way?

Finally, why would you want me, or anyone else who’s job it is to recount and interpret the past, to make any particular historical episode ‘look good’? Doesn’t that suppose a pre-judgement on your part, based on your patriotic feeling? Do you want just the British empire judged to have been a good thing so that you can feel better about being British? That’s understandable but only a polemicist would interpret the past in such a way as to generate that outcome. Especially when we are considering a phenomenon like colonialism, which by its intrinsic nature involves the invasion, occupation and exploitation of other countries. Good things for various groups of people, most obviously Britons, arose out of colonial situations, and I have identified these things and these groups in my work, but to engage in a moral comparison designed to make colonialism ‘look good’ is not something that conscientious historians should be doing.

Thank you for your response. I never actually expected to receive a response. I will look at my own definition of culture and try to understand the boundaries. By the way, I’m not an academic. I’ve worked as a criminal defense lawyer for the last 30 years. I consider myself an amateur historian; although I confess I read more historical fiction than actual history. It’s rare for me to read even a translated primary source. I would certainly agree with you that cultural differences are one way of attempting to hide racism. Then there are those who may not actually believe in a biological basis but use cultural criticism unfairly in a way that harms one racial group. Take the US, where I live, which has a problem with racism, particularly against Black people. There are those who will criticize almost all Black people in severe terms while not actually believing in Black biological inferiority. Yet their views are hard to separate from racism because they’re so strong. While views on culture may be an excuse for racism, their may be valid differences in cultures. For instance, as economies change, the British had a way of doing business that many people from other cultures wished to learn from. I readily grant that the British thinking they had a superior culture is not justification to conquer a supposedly inferior culture. Yet, as least as described in Biggar’s book, such beliefs didn’t generally motivate Britain taking over territory. When Britain did conquer other countries, those countries were often run by foreign invaders themselves. As to whether a historian should try to make history look good or bad for one side, I have to agree with you that the historians job is to be accurate as possible. I found your review by looking up criticism of Nigel Biggar. I don’t have anything against Mr. Biggar (whose book I purchased and read) or you (whose review I found helpful ); I just wanted to read the other side. With that said, I do believe myself to be a patriotic American. America is a child of Britain; the US political, legal system, and values derived far more from the UK than from any other country. You had mentioned whether I associate supposedly good culture from inferior culture with different races. I try, somewhat successfully, to not divide cultures into good or bad. One culture that in the US that seems to perform exceptionally well academically and economically is Asian people. Granted, there are huge variations; where I live, there are large numbers of Hmong people, who most likely due to not having a prior written language, have struggled to adapt to living in the US after their entry into the US following the Vietnam War. Why do Asian people in the US tend to outperform other races? A few decades ago, a book came out arguing that Asian people were biologically smarter. My own observation is that Asian people in the US tend to work extraordinarily hard in school and are extremely competitive; Asian people working super hard makes more sense to me. My understanding is the genetic scientists trying to correlate intelligence genes with race basically say their science is far too undeveloped to provide useful information. Colonialism by its nature involves invasion and occupation; exploitation sounds like a trickier term to apply. Empires by their nature tend to expand to benefit the empire, not the place to be occupied. However, the conquered often end up gaining benefits from the empire. The fearsome Mongols often turned into good rulers. When the Roman Empire was collapsing, many of the people in outlying areas regretted the loss of Roman rule. I worry that often we’re become so concerned with not minimizing the West’s negative impact on the rest of the world that we fail to see the accomplishments. Expounding on the virtues of non-White societies is commonplace; it is also appropriate when true. I view it appropriate to look at the virtues of the US and the UK. I note that at present both the US have large percentages of nonWhites. I live in California, which has a higher percentage of Latinos (39%) than Whites (35%).

I enjoyed reading this exchange between yourself and Dr Lester, thank you Ethel.

Dr Lester, if you had a moment, would you mind pointing me to one of your works that best addresses “Good things for various groups of people, most obviously Britons, arose out of colonial situations, and I have identified these things and these groups in my work”. Your catalogue is quite extensive.

Thanks Glen. I think the most detailed ex[position of mine is in Ruling the World” Freedom, Civilisation and Liberalism in the 19th Century British Empire, Cambridge, 2021.