In our last couple of blogs, we have proposed the merits of viewing the violence of 1857 as a global event: one which necessitated the mobilisation of a global network of communications, technology, people, and power, and made use of all the means of bureaucracy, diplomacy, logistics, and violence available to the British Imperial State and the East India Company.

In this two-parter, we will be exploring the events of 1857 from the centre in India, and from the ‘peripheries’, considering both how the resources of empire were tapped in order to mobilise troops for service in India and, on the other hand, how such mobilisation efforts affected policy development in other colonies. In this first part, we will focus on the Cape Colony, which supplied many of the regiments used to put down the rebellion in India. Next week, the blog will focus on how the Indian Government and India Office in England coordinated complex geostrategic and diplomatic efforts to move troops from England through Egypt and the Red Sea.

The Cape

The Cape Colony featured heavily in those efforts to mobilise the Empire to support India. While for the East India Company Board of Control and the Government of India, the Cape was a crucial resource for suppressing the rebellion, it is important to remember that the Cape government likewise had its own concerns. The Indian Uprising, therefore, from the perspective of the Cape, served as a significant, but peripheral, event that shaped, but did not overwhelm, domestic issues. It was the Colonial Office, meanwhile, that balanced these two perspectives, identifying the Cape’s value in meeting imperial priorities while also seeking to maintain the security and stability of the colony. It is the ways in which these perspectives coincided to shape Cape Colony policy that will be discussed here.

The Indian Uprising

The colony’s governor, Sir George Grey, enthusiastically responded to requests for troops, horses, ammunition, and food stuffs. His first report of the uprising came direct from the Governor of Bombay, rather than the central Indian government or the Home Government. In response, he sent large numbers of troops and horses. By the 22 September, he still had not received any direct communication from the Governor General of India and, feeling affronted at the lack of communication, suggests that he may have “gone too far” in his support of the Indian Government, and will henceforth “be cautious what other steps I take until further instructions reach me.”[1] Nevertheless, just two days later, he anticipates further Colonial Office instructions, by “gradually purchasing horses for the Indian Government” and expresses his intention to “continue to do so as rapidly as possible.” Despite the demand from India being only for 250 horses, Grey asserts his intention to “continue to act upon my own discretions, and ship so many horses as I can procure, until I think that the requirements of the public service in India are probably sufficiently met.”[2]

This virtual exuberance at the prospect of supporting the military effort in India is echoed in all the subsequent correspondence on the subject. In October, Grey reports the despatch of the Boscawen steam ship, with 500 men, plus officers and non-commissioned officers, and the simultaneous shipment of “trained artillery horses from the field batteries in this country…These horses and 250 additional men, with their due proportion of officers, shall be sent on to Calcutta in Her Majesty’s Steamer Megara at the same time the Boscawen sails.”[3] He likewise recounts how 92 officers and 1,743 men, sent from England, were diverted from their original destination in China to support the military in Calcutta.[4]

Grey appears to have taken a great deal of personal discretion in determining what support was necessary and to where it ought to be sent. He often exceeds the requests made of him, or offers provisions without provocation. Some of this might be attributed to inconsistent communications. Grey constantly complained that requests received from the Presidencies of India did not align with those sent by the Supreme Government of India or by the Home Government. He uses such communicational discrepancies to justify his own deviation from official instructions. At one point, he reports that at the same time that the Government of Bombay applied for two infantry regiments on the 23 September,

The Supreme Government of India, in communicating with this Government did not even ask for one Regiment. The instructions I had received from Her Majesty’s Government were to send one Regiment to Calcutta, and one Regiment to Ceylon, and there was a general authority in your despatch of the first of August to take, in conjunction with the authorities in India, such measures in regard to the movement of troops as the interests of the public service might require.[5]

It was not only troops that the Cape was asked to supply; as the Indian Uprising was being suppressed, the colony was also considered as a potential location to which ex-mutineers could be deported. Following the end of the Uprising, sending the King of Delhi to exile in the Cape Colony was debated. Grey eagerly proposed a plan in which the King would be sent to King William’s Town, the capital of British-occupied Xhosa territory named British Kaffraria, where he could be monitored, far from any chance of escape by sea and far from any influence in India. Slightly tangential to the primary point of this blog, but no less interesting for it, was the proposal made by Grey in relation to this proposed plan that “It would be better not to call upon the British Parliament to interfere in the matter, for the Legislature here will readily pass the necessary law upon the subject…moreover it is clearly right, in a colony possessing a representative legislature, with full legislative powers, that the interference of the British Parliament should be as infrequent and as little obtrusive as possible.”[6] This seems to contradict the general tone conveyed in many of Grey’s despatches related to troop disbursements, that the priorities of the Empire take precedence over the immediate needs of the colony. Rather here, he appears to be making a play for greater autonomy, distinguishing the Cape Colony as an independent colony with its own representative government, needless of imperial interference, even while pleading for greater investment on the grounds of its vulnerabilities.[7]

Domestic Cape Policy in 1857

Nevertheless, from the majority of Grey’s missives it is clear that the picture he painted for the Home Government was one of a colony willing to sacrifice its own security for that of another. Emphasising the benevolence and generosity displayed by the Cape colonial government, Grey points out that at the same time that they were supplying India with a larger force than had been asked for, the Cape “was embroiled in its own crisis with the native tribes.”

In highlighting the excessive amount of support offered to the Indian Government he likewise emphasises the resulting weakness of his own Cape force. Often, it is clear that such statements are made in the hopes of acquiring further financial and military support from the Home Government. In one despatch sent to request reinforcements from England, Grey reports,

We have crippled the artillery here by sending every horse from our field batteries, that we have temporarily almost destroyed the Cape Corps by taking two hundred of the best horses from that force, and this has been done with 70,000 barbarians within our Colonial Borders, exclusive of those in Kaffraria and the neighbouring states.[8]

Specifically, Grey was making reference to a series of cattle raids in British Kaffraria, mounted by abaThembu from across the northeastern border. In relation to many such conflicts, Grey highlights the weakness of the colonial army, as a result of the Indian Uprising, often making note of the increased role of volunteer and police forces in securing reputedly dangerous colonial borders. In October 1857, Grey boasted that with only the Mounted Police and Burgher Forces – a primarily volunteer group – a number of border chiefs were captured and convicted of cattle stealing. He reports:

I then caused him [the abaThembu regent Fadana] to be suddenly fallen upon by the Mounted Police and Burgher Forces, who, under the command of Commander Currie, performed this service with the utmost gallantry, discretion, and activity, and the result was, as you will find from the enclosed despatches, that Fadanna’s [sic] party were routed, in a great measure destroyed, and that the robber Chief, and his ally…were both captured.[9]

Grey likewise states his intention to further augment that Mounted Police Force with volunteers, so as to “get it into the highest state of efficiency; and that if we were compelled to enter upon any active military operations against the Native Tribes, such operations should be principally carried on by rapid movements of the Border Mounted Forces.”[10] He further touts the importance of the colony being “entirely under the control of the Government, in order that we may efficiently assist our Indian Empire.”[11]

Nevertheless, a common theme in many of the despatches leaving the Cape was one of security threats caused by the generous role played by the colony in supporting the Indian Government. In the context of the ongoing Xhosa Cattle Killing episode (1856-7) the ability of the colonial government to sufficiently suppress disturbances was likewise frequently spoken of.[12] In February 1858, four Xhosa chiefs imprisoned in the belief that they were conspiring to challenge the colonial government during the Cattle Killing, escaped from the prison at King William’s Town. The reports of this escape were considered all the more troubling as those chiefs, upon reunion with their people, were rumoured to be inciting violence against the British by invoking the Indian Uprising. In a despatch of 11 February, Grey reported to the Colonial Office the rumours of the escaped chiefs that had been reaching his office:

That all the troops had gone to India from England, but were so overpowered by the Indians that all the English troops had left this country for the purpose of assisting their countrymen. That all the horses had been shipped at East London, also the guns, and that the troops had embarked at Port Elizabeth and Cape Town. That it was heard with delight that the Indians are a black race with short hair, and very like the Kaffirs. That it is to be regretted that, whilst their race is overpowering the English in India, the Kaffirs are at the present moment unable to follow up the success, and fall upon the English in this country, and that it was known to his people that Krili [Sarhili] is looking forward to an opportunity and is devising plans for bringing on a war.[13]

“We maintain not a Garrison, but rather an Army”

You may have noticed at this point that discussion of the Cape Colony’s contributions have been largely focused on Sir George Grey and his reports thereon. There is a reason for this: accounts sourced from his despatches do not seem to match numbers found in official reports of the War Department and Colonial Office. Grey paints a comprehensive picture of a colony selflessly denuding itself of military resources to support the imperial agenda, all while battling frontier incursions from the inside. Meanwhile, the Home Government sees a very different picture: one of a colony receiving far more than their fair share of imperial resources and consuming a significant majority of available military funding.

The first suggestion that the Colonial Office was aware of the true size of the resources held by the Cape Colony is in November 1857, when the Secretary of State, Henry Labouchere, urges Grey to donate a portion of what they have to the effort in India.

You are fully apprised of the desire of H.M.’s Government that you should avail yourself of the circumstance of so large a number of troops being assembled in the British Provinces of South Africa to render the utmost assistance…to the Indian Administration, and pray that you will have been able to despatch considerable additional services to that Country, where seasoned Troops will be especially valuable.[14]

Keep in mind, that at this point Grey had, for some months, already been sending reports of vast exports of troops, horses, and other military resources to India, as well as complaining of the effect this had on the state of security in the Cape. It begs the question, therefore, why the Colonial Office would feel the need to encourage greater distribution of resources? Nevertheless, there seems to be little further reference made to any discrepancy until the following year, when the Indian Uprising was over.

A confidential report examining military expenditure in the colonies was circulated by the War Office in 1859, looking directly at the distribution of military resources across the Empire between March 1857 and March 1858. This did not include India because the East India Company still maintained its own force, despite in 1857 having received reinforcements from the general imperial army. In this report particular note was made of inequality among the colonies, both with regard to the amount of support they received from the Home Government, and the amount they themselves contributed toward their own defence. For example, while the colony of Victoria paid, in 1857-58, roughly two-thirds of its own ordinary military expenditure, Canada paid only one-fifth, and the colonies of Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Tasmania, and New Zealand all contributed nothing. The most stark anomaly, however, related to the Cape. The report of the War Office made special note of,

The drain on British resources which has resulted from our undertaking the defence of this colony, and to the inadequacy of the benefits resulting to British interests. As affording a field of emigration, a supply of our wants, or a market for our produce, our connection with the colony has not been, comparatively speaking, of any considerable advantage to us; in fact, the only direct object of Imperial concern, is the use of the road steads at Table and Simon’s Bays.[15]

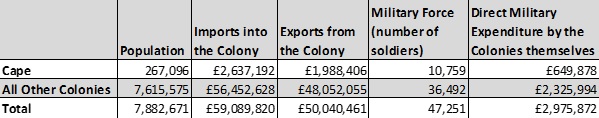

While Sir George Grey repeatedly bemoaned the dearth of military support in the Cape Colony in 1857, the report of the War Office actually suggests that for that year the Imperial government had at the Cape, including the German Legion, an army of 10,759 regular troops, costing them a total of £830,687, equal to more than one-fifth the military expenditure across the entirety of the Empire.[16]

A chart noting the relative military investment in the Cape Colony, in relation to its contributions toward the Empire and similar figures for all other colonies.

Source: Thomas Frederick Elliot. Memorandum, Colonial Office, 28 January 1860

In a minute thereon, Thomas Frederick Elliot of the Colonial Office reports that, in addition to those numbers, the Home Government additionally gave the Cape Colony a grant of £40,000 “for civilising the Kaffirs and averting disputes with the Natives.”[17] Elliot further complains, “It is true that these efforts have given us the satisfaction of being able to say that we have not had a Kaffir War, but nine or ten thousand troops constitute such an army as England seldom has to spare for less favoured spots.”

Omitting the Mediterranean garrisons, which Elliot qualifies as a “special class” he reckons that the Cape Colony received nearly a third of the direct military expenditure of the British Imperial Government in 1857-58.

Meanwhile, it is also worth noting that Grey repeatedly reported his use of civilians to maintain a volunteer and police force in lieu of military support. While he commended their effectiveness as a means of securing the colony against ‘native’ incursions apparently, in England, opinions differed somewhat. In fact, the only comment made in favour of retaining the exceptionally large garrison in the Cape was that, though “the Colonists would be willing enough to undertake their own protection provided that they might deal with the Kaffirs as they themselves consider best…this would entail a mode of warfare which would not be tolerated by public opinion in England.”[18]

Ultimately, it would appear that while the Cape Colony certainly contributed significantly toward efforts at putting down the uprising in India, reports relating to the detrimental effect on colonial security may have been exaggerated. Rather, it seems as though Grey might have utilised the Indian Uprising, as a means of overstating the colony’s insecurities so as to gain greater military and financial support for his wars against Africans. For the Home Government, while dismayed at the clear anomaly in how their resources had been spent, the solution was still unclear. Elliot himself sums up his minute thusly:

So long as British authority restrains the settlers from defending themselves in their own way, it is bound to find some efficient substitute. The result has been to produce an excessive drain of British resources for a single Colony; the expenditure, as above shown, is enormous, and it is not likely ever to be materially reduced except by a radical change of policy. Such a change would relieve this country from a heavy burden, and, so far as concerns the demands both for men and money, would be a palpable gain. Whether it would be opposed to any just claims of philanthropy, or to the general duties of the Sovereign States towards their subjects, and whether also it would be irreconcilable with public opinion, are questions of a different kind, lying beyond our province. They can only be determined by Statesmen engaged in the actual conduct of affairs.[19]

Sir George Grey was ultimately recalled from office in 1859, in consequence of the Home Government finally acknowledging the extent of the discrepancy between his protestations of resource starvation on the one hand, and the dawning recognition of the disproportionate expense that he incurred for little strategic or economic gain on the other. Yet historians have not yet noted how important the Indian Uprising was for both Grey’s and the Cape’s fate: it provided the prompt for Grey finally overstepping the mark, protesting rather too loudly both a self-sacrifice and a self-pity that drew newly critical attention.

Kate Boehme

[1] National Archives (NA), Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 22 September 1857.

[2] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 24 September 1857.

[3] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 3 October 1857.

[4] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 2 November 1857.

[5] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 24 September 1857.

[6] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, No.304, 11 November 1857.

[7] On Grey’s imperial politics at large, see Alan Lester, ‘Settler Colonialism, George Grey and the Politics of Ethnography’, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 34, 3, 2016, 492–507.

[8] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 2 November 1857.

[9] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 3 October 1857.

[10] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, No. 134, 27 August 1857.

[11] Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, 3 October 1857.

[12] See Jeff Peires, The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-7, Raven, 1989.

[13] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Jan – 31 May 1858, Letter from Sir George Grey to Henry Labouchere, No.9, 11 February 1858.

[14] NA, Cape Colony Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, Letter from Henry Labouchere to Sir George Grey, 27 November 1857.

[15] NA, Military Expenditure in the Colonies, War Office, 1859.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Thomas Frederick Elliot. Memorandum, Colonial Office, 28 January 1860.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

Leave a Reply