I have always planned to follow-up my undergraduate studies with a policy course. My work in different themes of development: poverty reduction, education, water and sanitation, health care and environment had clearly illustrated to me that access to efficient, clean and affordable energy is the key to human development efforts. And that Climate Change is another huge issue on the global agenda.

I have always planned to follow-up my undergraduate studies with a policy course. My work in different themes of development: poverty reduction, education, water and sanitation, health care and environment had clearly illustrated to me that access to efficient, clean and affordable energy is the key to human development efforts. And that Climate Change is another huge issue on the global agenda.

I had started to explore the role that science, technology and innovation plays in international development, through my previous studies and work in international development: I took trips with a friend to some off grid remote farming and nomadic villages in Nigeria’s North Central region, to understand how the people lived without access to electricity and other energy services. I am interested in exactly what hinders people in these villages from having access to efficient and clean energy. I also visited island communities in Lagos for the same purpose. These visits helped me take the final decision to study an energy, innovation, and sustainability related policy course.

I quite easily found the ‘Energy Policy for Sustainability‘ programme offered at the Science Policy Research Unit, University of Sussex, on-line. I met the entry requirements, applied and was offered a place. I arrived on campus to an experience that would be one of the most exciting academic and learning experiences I may ever have. I was not surprised that I enjoyed the course – I was motivated even before arriving for my studies. Weeks before arrival, the course convener had shared a reading list to serve as an introduction to the course. This was particularly helpful to me.

The lecturers and faculty members are passionate about their work, teaching and sharing their experiences. The classes are interactive and held in ‘safe environments’ which means that students are protected from any undue influence from lecturers, staff and fellow students.

Course seminars were the best classroom activity for me as they afforded students the opportunity to share knowledge and experiences, to discuss and argue on related topics and to get to know each other better, outside the usual university social events.

There are weekly (non-compulsory, but necessary) seminars on energy, climate change, science, technology, innovation, development and many other energy related fields. These are delivered by visiting researchers from other universities and research centres. I benefited hugely from the few that I was able to attend; from recent ground breaking research findings to new thinking around old ideas and approaches. The seminars are an opportunity to challenge the normal thinking and disrupt the system at little bit. It was very encouraging to attend – Masters Students were always given priority over PhD candidates and faculty members during the comments and Q&A’s that follow the presentations. Everyone’s opinion and point of view were welcome, sought out and respected. Personally, I was usually given time to express some knowledge I had and to get validation from the answers or comments that I received. It’s also a good way to meet the rest of the SPRU community and to build friendships and valuable networks.

The lecturers were welcoming, especially in classes that I had voluntarily opted to take and for which I wouldn’t be assessed. They were encouraging, helpful and always responsive. The most exciting moment for me was when I proposed to use the STEPS Centre’s Pathways Approach to do an analysis for one of my term papers. The encouragement I got is something I will never forget. STEPS Pathways Approach is a new concept and it was unusual for me to use it for my term paper. I successfully did though, and with deepest thanks to my lecturer, today I am drafting a STEPS Working Paper out of that term paper. The encouragement I had from him is what I would wish for every student. It is not difficult to get that in SPRU – just challenge yourself and ask for help and encouragement.

I enjoyed my studies so thoroughly that I was very willing to be an ambassador for the course programme at the Postgraduate Open Evening and subsequently helped produce an official video to promote courses that SPRU offer including Energy Policy for Sustainability.

On graduating, I feel ready to work in any context that I find myself. Be it a policy, research or advisory position, consultancy, government, non-profit, business or academic. I am ready! I couldn’t be more proud to have passed through SPRU and SPRU through me. I have gained a deep understanding of the different and complex factors, dynamic interactions and contexts that challenge the development and governance of efficient, low-carbon energy systems and technologies in the 21st century. Not only have I gained tremendous knowledge but I understand how to operationalize energy policy instruments and strategies to effectively achieve the desired outcomes.

Taking the Energy Policy for Sustainability course at SPRU is something I strongly recommend to anyone; you only have to be passionate about understanding our energy systems, making energy services more accessible and efficient, and keeping our environment and world, safe from climate change impacts.

For me, there is still a lot more that SPRU has to offer. I am keeping in touch with the SPRU community and who knows – I may be going back there soon.

Okafor Akachukwu

Follow Sussex Energy Group

The Green Deal was primarily marketed as a financial proposition saving households money on their bills. Instead of a universal, top-down, marketing approach, we should learn from DECC’s own survey evidence that a multitude of factors beyond purely financial considerations motivate people to improve the energy efficiency of their home. A more effective marketing strategy needs to draw on those insights and speak a language that addresses consumers’ desires and requirements.

The Green Deal was primarily marketed as a financial proposition saving households money on their bills. Instead of a universal, top-down, marketing approach, we should learn from DECC’s own survey evidence that a multitude of factors beyond purely financial considerations motivate people to improve the energy efficiency of their home. A more effective marketing strategy needs to draw on those insights and speak a language that addresses consumers’ desires and requirements.

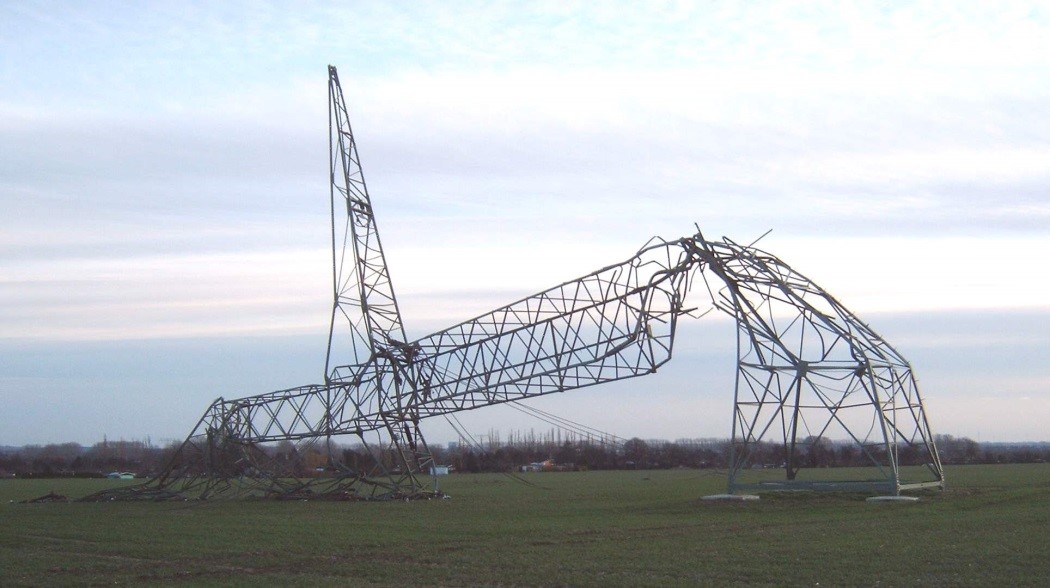

As seems more and more the case in recent years, energy security is top of everyone’s agenda, probably at least in part due to recent reporting of

As seems more and more the case in recent years, energy security is top of everyone’s agenda, probably at least in part due to recent reporting of  Emily Cox is a Research Assistant and PhD student with the Sussex Energy Group at the University of Sussex. She is a researcher on the ‘DiscGo’ project on discontinuity in socio-technical systems, with a focus on power and incumbency in the UK nuclear industry. For her PhD she is researching electricity security in the context of a low-carbon transition, developing a methodology which can be used to assess low-carbon transition pathways for their resilience, affordability and sustainability. Emily is also currently a research intern at Oxford University, examining the role of the public in meeting the UK carbon budgets. Emily has 3 years’ experience as an Associate Tutor at the University of Sussex, tutoring an MSc in Energy Policy and an undergraduate module in energy transitions. She recently worked for the Royal Academy of Engineering, undertaking research into the social and economic impacts of electricity shortfalls. She has also spent time working for E.ON Technologies at the Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station, researching energy security, district heating, distributed storage, and the UK Capacity Market. She previously worked as an area coordinator for Greenpeace. She holds an MSc in Climate Change and Policy, a BSc in International Relations, and half of a rather ill-advised BA in music.

Emily Cox is a Research Assistant and PhD student with the Sussex Energy Group at the University of Sussex. She is a researcher on the ‘DiscGo’ project on discontinuity in socio-technical systems, with a focus on power and incumbency in the UK nuclear industry. For her PhD she is researching electricity security in the context of a low-carbon transition, developing a methodology which can be used to assess low-carbon transition pathways for their resilience, affordability and sustainability. Emily is also currently a research intern at Oxford University, examining the role of the public in meeting the UK carbon budgets. Emily has 3 years’ experience as an Associate Tutor at the University of Sussex, tutoring an MSc in Energy Policy and an undergraduate module in energy transitions. She recently worked for the Royal Academy of Engineering, undertaking research into the social and economic impacts of electricity shortfalls. She has also spent time working for E.ON Technologies at the Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station, researching energy security, district heating, distributed storage, and the UK Capacity Market. She previously worked as an area coordinator for Greenpeace. She holds an MSc in Climate Change and Policy, a BSc in International Relations, and half of a rather ill-advised BA in music.