During our recent workshop, Daniel Clayton emphasised the importance of reflecting on where meaning congeals when investigating the impact of events and ideas across an empire. This approach is no more important than when considering the impact of the Indian Uprising of 1857. In India it represented a direct threat to European lives and property, and the authority of colonial rule; in London it represented a challenge to Britain’s reputation as the dominant global power, and a potential risk to colonial control across the empire. In many of the colonies, however, the Indian Uprising was primarily a distant crisis and a draw upon imperial resources. In our last two blogs we sought to demonstrate how the Indian Uprising spurred a mass mobilisation of imperial resources across the globe, as both human and ‘more-than-human’ entities were concentrated in the subcontinent. It would be easy to view the uprising as a centralising force, to apply that regional meaning across the empire. However, as we remember Clayton’s observations, it becomes clear that meaning does not congeal uniformly ‘everywhere and all at once.’ Rather, as will be demonstrated in this blog, the Indian Uprising existed as a peripheral event to many, its impact distant and indirect.

In fact, many colonies remained blissfully detached from events occurring on the other side of the globe, too concerned with local issues to spare much thought for such a distant crisis. This post will explore these ‘peripheries of 1857’ where, despite their own inward perspective, colonial administration was still inevitably affected by global imperial agendas. It will likewise focus upon the role occupied by the Colonial Office – in cooperation with the other offices of the home government in London – as a mediator, maintaining a global perspective and the concept of a united British Empire, even as the colonies retained singularly localised outlooks.

The peripheries of the empire in 1857 therefore provide an interesting insight into the processes of triage employed by the Colonial Office during periods of crisis. While our last blogs explored how imperial resources were mobilised to serve a single purpose, this one will now investigate how, in spite of that seemingly singular focus, business-as-usual was preserved across the rest of the empire. With so much energy directed toward a single cause, methods of triage were employed to determine how remaining resources were distributed to ensure stability and that other imperial imperatives were maintained. This blog will focus on a few colonies that remained peripheral to the main crisis of 1857 and their engagements with the Home Government and the Empire as a whole.

Saint Helena

The case of St. Helena demonstrates the importance of communication networks for retaining a connection to the wider empire, as well as how associated technologies were unevenly distributed among the colonies. St. Helena was not only geographically isolated, but also communicationally and commercially isolated from the rest of the Empire. It received very little investment from the central government, as it was seen to hold only a very minor role in the promotion of imperial interests. While the Cape Colony commanded nearly one fifth the military expenditure spent across the British Empire, St. Helena received none. Once a crucial re-fuelling station, by 1857 St. Helena was relegated to a peripheral status within transoceanic and global networks of communication and transport. This placed it outside the central sphere of military and political interest, relegated to a position of only tertiary importance, with no standing imperial military and little external investment.[1] In fact, while the colony was often used by traders as a way-station on their travels between Europe and East Asia, it appears that it was not used by the military at all. In 1857, the Governor of St. Helena, Sir Edmund Hay Drummond Hay, received an offer from the United States of America Government, proposing the establishment of a naval depot on the island. Wishing the British to have first right of access to the strategic advantages ostensibly offered by St. Helena, Governor Hay wrote to the Colonial Office, describing “the well recognised advantages of geographical position, safety of roadstead, abundance of pure water, fresh provisions, and supplies of all kinds,” as well as the “peculiarly healthy climate of St. Helena [that would] add much to its value as a Naval Station.”[2] Ultimately, however, the Colonial Office consulted with the Admiralty and determined to allow the deal with the Americans.

This decision is certainly representative of the lack of strategic interest which St. Helena commanded. The Colonial Office made a crucial decision to allow the island – which produced little internal revenue – to raise funds by renting land to a foreign power rather than invest resources in the colony. In 1857 the empire had little military resources to spare, but likewise they were interested in levying any and all assets they had. St. Helena clearly fell to the bottom of the list, both as a recipient and as a possible contributor toward the strategic interests of the empire.

The same seems to have applied to the commercial sector, which chiefly benefitted from the occasional visit of a merchant vessel looking to restock and refuel en route from Asia. As a result, it appears that the colony found itself struggling to maintain basic living standards for the small community of local residents. Far from being able to fund their own military, St. Helena struggled to finance basic infrastructure, even in the capital. James Town, the capital city of St. Helena, lacked a complete drainage system. In 1854, a project had been approved that would pave the main drain in James Town, making possible higher sanitation standards in the city. The paving was necessary for any future “arching over,” which would place the sewage drain underground, thereby improving public health standards as well as expanding the land area available for construction. However, a lack of funds had seen the work delayed for several years.

It was here therefore that the extent of the reliance upon local officials to maintain the day-to-day health of the empire is most readily apparent. Originally intended to be funded in part by the War Office, this infrastructure project had been delayed as a result of having never received the funds. By 1857 the situation was dire, with the need for higher sanitation standards in the city becoming ever more pressing, while the availability of funds from the imperial government to support colonial maintenance projects on the strategic periphery were at an all-time low. Governor Hay, therefore, developed a somewhat innovative plan whereby the drainage works would be completed gradually over time, drawing solely on surplus colonial revenues. The Colonial Office were happy to approve a scheme that would sever the Home Government from responsibility for financing colonial infrastructure, and allow their resources to be directed elsewhere.[3] It was likewise for these reasons that the Colonial Office similarly approved the building of an American naval depot on St. Helena, declining to use the island’s facilities for British purposes.

Trinidad

While St. Helena was isolated from the whole of the Empire, Trinidad remained closely connected with other colonies in its vicinity and with consumer markets in Europe, despite being distant from events in India. Its government retained a uniquely Caribbean perspective, focused upon the protection of local industry. A surge in sugar prices in 1857 inspired a significant expansion in cultivation which, in turn, required a larger supply of cheap agricultural labour. In the decades following Emancipation, this need had primarily been met by Indian indenture, and the onset of the unrest on the subcontinent was not to deter demand. Despite the supposed preponderance of free trade ideologies at this time, it is clear that the protection of Caribbean sugar interests was seen as a priority in England. It was a convenience that meeting consumer demand for sugar in England intersected with the punitive agendas of Indian lawmakers.

At the end of 1857, the uprising was mostly over, and the Court of Directors of the East India Company was debating what to do with the population of former mutineers. Most agreed that Transportation was the best course of action for dealing with the majority, but a conclusion as to where they should be sent was yet to be made. Colonies such as Trinidad, which were desperate for labour, began bidding to receive the convicts. In November 1857, Governor Robert W. Keate of Trinidad forwarded a report presented by the Chairman of the Standing Committee of the Council on Immigration in Trinidad, presenting a plan by which the colony proposed to accept minor offenders from among the Indian mutineers. The Chairman and Governor proposed a plan whereby “however penal in its nature the expatriation of these offenders might be made, their reception in Trinidad would not bear that character.”[4] In other words, instead of maintaining a separate, and costly, Convict Establishment on the island, they proposed to integrate the deported mutineers into the general Indian indentured labour force. They suggested that the mutineers would be indentured to agricultural labour for a period of ten years, “but with power reserved to the Governor of transferring their services or cancelling their indentures.”[5] Far from expressing worries that the mutineers might inspire similar unrest among the existing Trinidadian indentures, or for the general security of the colony, the Trinidad colonial government promoted a plan that prioritised the efficacy of this new work force by pushing for total integration:

I fear that…a contract of such duration with the same employer would present too servile an appearance, and that the distinction between the two classes of Indian labourers would therefore be too marked. It would be preferable, I think, that these deported immigrants, as I would call them, should be assigned for that length of time to the local Government instead of to individual employers, and that this assignment should take place of, and operate in the same way as, the obligation to the residence of ten years now imposed by the Immigration Ordinance No. 24 of 1854 on voluntary Indian immigrants. The labour indentures of both classes should then, I think, be made identical in duration, and the same right of purchasing their time might be extended to both.[6]

In fact, the demand for inexpensive labour in the Caribbean colonies was such that it inspired rivalries. Trinidad repeatedly bemoaned the perceived favouritism shown to the nearby colony of British Guiana in the distribution of deported mutineers. Governor Keate complained that British Guiana received privileged access to this ready supply of labour, as well as receiving advantages in the usual avenues of labour acquisition, in the form of a representative agent for emigration posted in Bombay. Keate complained that if British Guiana were permitted an Emigration Agent in Bombay, so too should they be, so that Trinidad could also gain access to the “higher calibre” migrants.[7]

This inter-colony tension similarly reared its head when gold was discovered on the border of British Guiana. Trinidad raised repeated concerns that the prospect of gold would inspire agricultural labourers to abandon their fields, and indentures to flee their contracts, to seek their fortune in the neighbouring colony.

British Guiana

British Guiana, meanwhile, seemed not to return much of the animosity directed their way from Trinidad. They expressed similar concerns for their ability to provide workers for the sugar plantations, but were primarily preoccupied with issues of domestic unrest. Chiefly, this centred upon a border dispute with Venezuela, inflamed by the discovery of gold. In aiming to meet their needs in this regard, British Guiana made repeated requests to the Home Government for support, showing little-to-no understanding of how London’s attention might be divided in meeting demands for military, financial, and diplomatic support.

Like Trinidad, British Guiana was primarily a plantation economy, and similarly desired to increase their supply of inexpensive, agricultural labour through the increased importation of Indian indentures. In one instance, the colony was eager to establish a convict settlement from whence the prisoners would be relegated to agricultural work.[8]

In 1857, the colony was granted permission to station an Emigration Agent in Bombay to represent their interests in recruiting labourers, a fact that, as already noted, irritated other colonies that were denied such powers.[9] Inter-colony struggles to control the labour market in this region were not a new event in this region; dating as far back as the late-1830s, in the years following the end of Apprenticeship, Barbados, Trinidad, and British Guiana all attempted to influence the movement of labour. British Guiana, in particular, was known for setting up financial incentives to encourage former slaves to emigrate there from other colonies.[10]

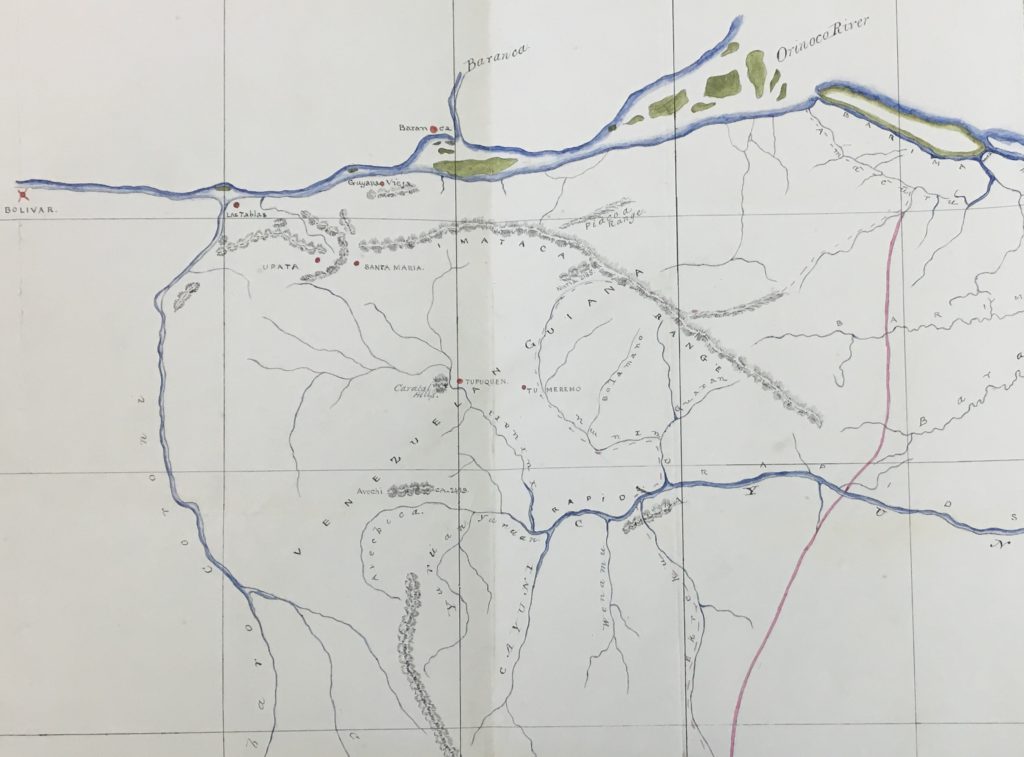

The discovery of gold on the Venezuelan border of British Guiana not only exacerbated these inter-colony tensions, but also reinvigorated a standing boundary dispute. The gold was found at Upata, in a mountainous region separating British and Venezuelan territory. The exact line, however, separating these two regions of Guiana had been under dispute for some years, with multiple reports placing the border at varying points. The River Orinoco, for example, was but one possible border line, as well as carrying greater importance for its being the primary artery from the coast and the only major waterway into the Upata region. With the mouth of the Orinoco currently under British control, the government of British Guiana was anxious to ensure proper protection for this strategic holding while the border dispute was being settled. They requested a naval ship of war be posted at Point Barima, at the mouth of the Orinoco, to prevent its occupation by any foreign powers. In response the Admiralty pointed out that simply no ships of war were then available to stand guard, prompting Secretary of State for the Colonies, Henry Labouchere, to assure the colonial government that he “considers it to be very desirable that in due season a Ship of War should…visit the mouth of the Orinoco for the protection of British interests” even if such action was, at that time, not possible.[11] The missive likewise urged the colonial authorities to make every effort to themselves secure British interests in the region. In other words: the Home Government made clear that the colony was responsible for protecting its own borders and that no imperial resources were at that time available to help.

The border dispute with Venezuela is an interesting example of a local concern that intersected with wider imperial agendas. While eager to lay claim to profits from the gold, the Home Government were not so keen that they were willing to jeopardise peace in the region. Though settlement of the border was imperative if they wished to claim gold, it was equally important for protecting British sovereignty in the region against the claims of the Venezuelans and, most ominously, encroaching American businesses. Upon closer examination, we therefore find that the Colonial and Foreign Offices liaised closely on this subject despite being anxious to not inflame tensions, and unwilling to dedicate financial or personal resources to its settlement. There are clear processes of triage at work here, as diplomatic and knowledge-based solutions were sought in lieu of military options.

Old surveys and maps were favoured over new exploratory expeditions. The colonial government’s repeated sending of survey teams to assess the landscape was strongly opposed by the Home Government. This was particularly true of groups sent to view the gold fields at Upata. The colonists claimed that the expeditions were “composed of British subjects having no intention of infringing any rights of the neighbouring country, but merely of ascertaining and reporting upon the position and prospect of the deposits of gold so as to enable the government of British Guiana to take such steps as may appear advisable.”[12] In so doing, their primary objective, in addition to ensuring that any possible claim to gold was capitalised upon, was to respond to rumours and hearsay within the colonial community and in the media, that the gold was British. Nevertheless, such expeditions risked being seen to aggressively violate Venezuela’s territorial sovereignty. Not being in a position to support any conflagration in the region, the Home Government therefore strongly opposed the sending of survey teams. Instead, they relied upon pre-existing surveys and, most importantly, maps revealing the colony’s territorial boundaries while it was still under the control of the Dutch. Reports from the colony were consulted along with those from the Foreign Consul in Venezuelan Guiana, as well as maps and historical surveys.

One theorist to whom the colony referred in their reports on the matter was Sir Robert Schomburgk, thought to have outlined the most likely boundary in his map of the region. In addition, were others such as Bouchenveder’s map, which suggested a more liberal boundary, giving more territory to the British:

I have carefully perused the correspondence upon the subject of our boundary which took place between Her Majesty’s Government and the Venezuelan Minister in 1841-42, and as the Government of the province of Venezuelan Guiana was allowed to remove the landmarks planted at Point Barima by Sir Robert Schomburgk, although without prejudice to the claims of Great Britain, and that Point is at the entrance of the only channel of the Orinoco navigable by vessels of any great burden, it is obviously desirable that all doubt should be removed as to its rightful possession. I have been as yet unable to trace any memorandum of the data upon which Sir Robert Schomburgk based his survey, but no doubt such exists in the archives of the Colonial Office…In Bouchenveder’s map, it is distinctly laid down that a Dutch post existed on the right bank of the River Barima thus indicating that stream, as the natural and actual boundary in that locality, between Spanish and Dutch Guiana.[13]

Acknowledging the urgency of settling the boundary, the Colonial Office communicated with the Geographical society for any information of the Dutch post mentioned by the Lieutenant Governor. Information concerning the historic boundary – that which had been delineated by the Dutch before handing over the territory to British control – was seen as the most certain way of confirming the boundary without any conflict or need for extra resources. The settlement of the boundary would, in turn, clearly place any gold on either Venezuelan or British land, thereby establishing ownership. Since any reasonable settlement – the Bouchenveder plan being seen to be far too ambitious – was likely to favour the Venezuelans in this regard, the Colonial and Foreign Offices used the British Consul in Bolivar to negotiate for the use of British Guiana as an avenue to those lands, using their control of Point Barima to their advantage. According to this plan, the colony would benefit from the commerce of gold-seekers and merchants, if not from the gold itself.

The boundary between Venezuelan and British Guiana held very real political and economic implications for the region, yet it was settled not through the application of physical resources – such as military, personnel, or money – but rather through the implementation of that paper-based empire. Maps and surveys, used to document the physical geography of the region, were seen as an alternative solution to a complex geopolitical problem.

British Honduras

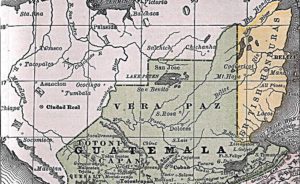

A border dispute similarly featured at the centre of colonial politics in British Honduras, which at this time was governed by a Superintendent, serving under the authority of the Governor of Jamaica. The post was held by Frederick Seymour, who wrote regularly of issues along the border shared by the colony and Mexico. The boundary in this case was settled as lying along the Hondo River. However, delegation of responsibility for maintaining border security remained uncertain, as did that for the people who moved across the border. Migration was common from both sides, with tribal peoples from the Yucatan moving into the British colony, and colonial logging firms travelling onto Mexican lands in pursuit of valuable trees.

In May 1857, the Chichanha tribe moved across to the British side of the Hondo, fleeing the hostility of stronger tribes in the Yucatan. They then proceeded to cut down mahogany trees to create a settlement, which threatened the local logging industry. Superintendent Frederick Seymour found himself responsible for determining not only whether to allow the Chichanhas to stay and how many British resources were to be redirected toward defending the border against the tribes who sought to follow them, but also how to best mediate relations between the Chichanhas and local loggers. Seymour expressed a fear that a collision between the Chichanhas and the mahogany cutters “could be embarrassing, especially so close to a disputed frontier.” With no support available from either Jamaica or England, and little military at hand domestically, Seymour sought a diplomatic solution, suggesting “the tribes attracted to our settlement by the protection which it ensures against the attacks of their enemies may be induced to remain therein; and dispersing into smaller bands, advance to the interior where their services would be valuable as labourers and timber cutters.”[14]

As in St. Helena, the situation in British Honduras highlights the extent to which the Colonial Office depended upon the actions of individual characters for the maintenance of a stable empire. Despite British Honduras being officially controlled by the Governor of Jamaica, it was the Superintendent of British Honduras, Frederick Seymour, who made the critical decisions that determined refugee policy, balanced commercial and political agendas, and ensured the security of the border with Mexico. By the time the Colonial Office received word of events in the colony, the information had already been filtered through the government in Jamaica and was, as a result, several weeks old. They relied upon the dependability of local governors to ensure that the colonies remained stable, and that the image of British global dominance, and the conceived global empire, were being preserved.

Conclusion

The cases illustrated here have been selected to give a sense of the myriad issues occurring around the globe in 1857. Together, they demonstrate the different ways in which colonies related to the central government and to each other; it points to the regional concerns and themes that pre-empted the Indian Uprising in the imaginations of colonies on the global periphery. It moreover illuminates the means by which the Colonial Office navigated this complex web of inter-colonial relations to preserve a sense of an imperial community, united under the flag of the British Empire. From London, the Colonial Office performed acts of triage, prioritising issues in the colonies, analysing their importance for the imperial agenda, and distributing resources accordingly. They employed alternative methods, communicating closely with other government offices to ensure the most efficient, and cost-effective methods were employed. They also relied upon a network of colonial officials in the absence of reliable avenues of immediate communication to preserve the day-to-day stability of colonial life. Ultimately, the Colonial Office however chose to defer many problems. By encouraging colonies to engage in knowledge-collection and in protecting the status quo, they in many instances deferred action until a time when the consequences could be better dealt with.

Kate Boehme

[1] Most colonies retained a combination of colonial-funded and British-funded military resources, with the amount of the latter usually connected to perceived vulnerability and strategic importance to the interests of the wider British Empire.

[2] National Archives. Saint Helena Despatches 1857. “Sir E.H. Drummond Hay to Secretary Henry Labouchere,” (30 Nov, 1857).

[3] National Archives. Saint Helena Despatches 1857. “Sir E.H. Drummond Hay to Secretary Henry Labouchere,” (16 May 1857).

[4] National Archives. Trinidad Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, No. 113, “Governor Robert W. Keate to Secretary Henry Labouchere, (6 Nov, 1857).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] National Archives. Trinidad Despatches 1 Sept – 30 Nov 1857, No. 89, “Governor Robert W. Keate to Secretary Henry Labouchere, (5 Sept, 1857).

[8] National Archives. British Guiana Offices 1857, No. 1115, “Foreign Office to Colonial Office,” (9 Feb, 1857).

[9] National Archives. British Guiana Despatches 1 Jan – 30 April 1858, No. 11, “Lieutenant-Governor William Walker to Secretary Henry Labouchere,” (23 Jan, 1858).

[10] Alana Johnson. “The Barbados Emigration War,” presented at After Slavery? Labour and Migration in the Post-Emancipation World, (27 June, 2016).

[11] National Archives. British Guiana Offices 1857, No. 9356, “Foreign Office to Herman Merivale,” (9 Oct, 1857).

[12] National Archives. British Guiana Offices 1857, “R. Bingham to Mr. Gutierrez,” (14 Sept, 1857).

[13] National Archives. British Guiana Despatches 1 July – 31 Dec 1857, No. 20, “Lieutenant Governor William Walker to Secretary Henry Labouchere,” (24 Sept, 1857).

[14] National Archives. British Honduras Despatches 1857, Confidential Despatch No. 1, “Superintendent Frederick Seymour to Lieutenant Governor Major General Bell, (15 May, 1857).

Leave a Reply