One of the Brexit populists’ most successful political strategies, played out in the recent Tory leadership contest, has been culture war: an assault on reformist and liberal agendas including anti-racism, that are now condemned as “woke”. With Suella Braverman Priti Patel’s successor at the Home Office, it shows no sign of abating. A key plank of the strategy has been attacks on those who attempt to educate and inform the public about the racial discrimination and legacies of the British Empire, the latest manifestation being the conservative activist group Restore Trust‘s ongoing attempt to pack the National trust Council with members who will censor it from saying more about the role of slavery and colonialism in its properties’ history. Accusations that those who try to educate about the empire are ‘anti-British’, however, are not entirely novel. They are contemporary twists on debates about the Empire staged over the last 200 years. When enslaved people secured emancipation and indigenous people raised their right to survive the onslaught of British colonisation, their liberal allies in Britain faced a similar conservative backlash. It may not have been referred to at the time as a culture war but it did much to shape enduring divisions over race in Britain and Britain’s place in the world.

After Black Lives Matter protestors toppled slave trader Edward Colston’s statue in June 2020 the government’s “war on woke” reached new levels of intensity. Robert Jenrick declared “We will save Britain’s statues from the woke militants who want to censor our past” and Oliver Dowden instructed Britain’s leading museums, galleries and heritage organisations that they “must defend our culture and history from the noisy minority of activists constantly trying to do Britain down”. The right wing press followed up with hyperbolic articles about the interpretation of colonial heritage. The torrent of hysterical reaction to small things, such as the decision in May 2021 of some Oxford graduate students to take down a picture of the Queen, became relentless.

This manufactured hysteria has politicised Britain’s heritage to a degree unimaginable just a few years ago. Some of the rhetoric in the Mail’s online forums reflects the belief of the trans-national extreme right in The Great Replacement. This bizarre notion of an existential threat to White racial survival stemming from fellow citizens of colour and their “woke” allies is what motivated the terrorist atrocities in Oslo in 2011 and Christchurch in 2019. Boris Johnson’s advisor on race, Samuel Kasumu, quit recently, complaining that “some people in the government … feel like the right way to win is to pick a fight on the culture war and to exploit division.” These elements, Kasumu feared, were facilitating a repeat of the murder of Jo Cox’, the Labour MP killed by a right wing racist in 2016. While it might be more subtle, the Telegraph’s use of “woke” is also not so far from the idea of a “collaborator” with sinister forces threatening White people. It has ranted that the woke “want to make all White people feel guilty and feel ashamed of their skin colour. In a White majority country”.

All this conservative culture war activity echoes the backlash against liberal concern for colonial subjects of colour that began in the context of a reforming British Empire in the early nineteenth century. Enslaved and colonised peoples themselves played the leading roles in securing emancipation and representing their communities as best they could in Britain, but like Black Lives Matter activists, they were working in alliances, often tense ones, with White allies. Some of the most illustrious and famous conservatives of the day led the charge against them.

When sugar production plummeted in the wake of emancipation in Jamaica and the 1846 Sugar Duties Act abolished the former slave owners’ preferential rates on sugar imports, one of the most famous critics of the day, Thomas Carlyle, fulminated against both the “naïve” philanthropists and the free trade economists, who, between them, had helped free slaves into a state of wage labour while abandoning British planters. Carlyle argued that emancipation had condemned Black Jamaicans to idle pauperism, just as greater freedom had the Irish. The Irish, he argued, had been reduced to “human swinery”, a “black howling Babel of superstitious savages” during the Famine. In a deliberately provocative article, which he boasted “you will not, in the least like” entitled “Occasional Discourse on the Negro [later substituted for the N word] Question”, he described the freed slaves of Jamaica “Sitting yonder, with their beautiful muzzles up to the ears in pumpkins, imbibing sweet pulps and juices; the grinder and incisor teeth ready for every new work; while the sugar crops rot round them, uncut, because labour cannot be hired”.

Despite the protests of liberal friends like John Stuart Mill, Carlyle’s unabashed racism sharpened and articulated the British public’s sense of disappointment in Africans’ ability to become “civilised”. Together with the stream of racial invective pouring into British homes from colonial newspapers extracted by the British press, in the private correspondence of settlers to their contacts at home, and in publications such as the Memorials of the Settlers in the Eastern Cape, it reinforced the notion that white Britons had a particular, if not unique, claim to that mantle.

The most popular author of the day, Charles Dickens soon arrayed himself alongside Carlyle as a leading mid-nineteenth century culture warrior. In October 1857, when news of the Indian Uprising massacre of 120 British women and children at Cawnpore dominated the British press, Dickens summed up the public’s mood of vengeance: “I wish I were the Commander in Chief in India …. I should do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested … proceeding, with all convenient dispatch and merciful swiftness of execution, to blot it out of mankind and raze it off the face of the earth.”

Carlyle and Dickens ridiculed people like Thomas Fowell Buxton, who had taken over from Wilberforce as the leading anti-slavery and colonial humanitarian campaigner. In the wake of the abolition of slavery, the two writers asserted that philanthropists and missionary supporters had been proved wrong. The formerly enslaved had not diligently continued to work on the plantations, as philanthropists had promised. Instead, they had sought to reunite families torn apart when parents and children were sold to different owners.

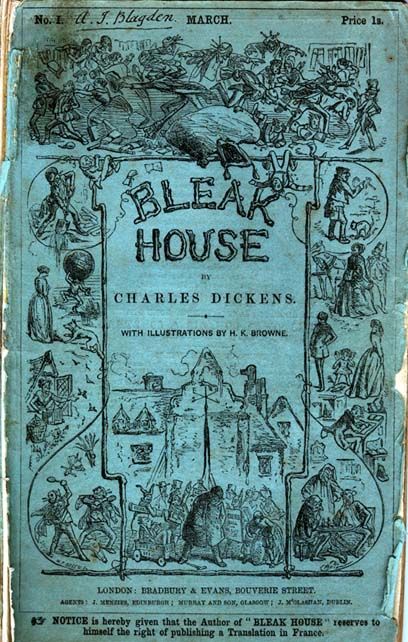

The lesson, however, was not that family could mean as much to Black as to White British subjects. It was that Black and indigenous people had squandered the freedom, and the gift of civilisation, that the British had offered them. Dickens’ Bleak House helped to invent the stereotype of the “woke”; the cause-obsessed, misguided and dangerous philanthropists who had helped them waste the opportunity. The book’s character, Mrs Jellyby, summed up nineteenth century wokeness. She is so preoccupied saving the souls of heathen Africans she has never met that she neglects her own children. White British children like the road sweep Jo, die pitifully on the streets of London while the “humanitarians” extend their sympathies only to distant savages, who refuse to learn. Rather than continuing with their “telescopic philanthropy”, Dickens moralised, Britons should focus on the needs of White kith and kin at home.

If a conservative reaction against the “woke” is nothing new, neither is the leading role taken by a Prime Minister. On the day that Boris Johnson became Prime Minister I came across the following extract from Reynolds’s Newspaper on Lord Palmerston, the Liberal PM in 1857: “What a truly melancholy exhibition! The foremost nation of all the Old World rushing, and screaming, and swearing, and shouting in mad hysterical hallelujahs, the praises of a man whose principal characteristic was an unconquerable disposition to jest at national calamities, and whose greatest recommendation was a species of boasts”. When Laurence Fox , himself a vocal right wing culture warrior, played Lord Palmerston in ITV’s Victoria, he admitted that the character “may have had a bit of the Boris about him”. Johnson and Palmerston shared undiplomatic careers as womanising, flippant Foreign Secretaries and a wit and charm that made them popular with large sections of the public, if not always with their peers in parliament. The parallels do not end there, however.

In 1857, Palmerston wanted war with China, which had had the temerity to prevent British ships illegally smuggling opium into Canton. Palmerston’s government intended to force Chinese markets open to “free trade” from British narcotics and industrial manufacturers. His problem was that many of his own liberal MPs objected to the war on moral grounds. Lord Lyndhurst asked, “was there ever conduct more abominable, more flagrant, in which … more false pretence has been put forward by a public man in the service of the British government?” After it became clear that British officials had ordered the shelling of the city, Parliament passed a motion, carried by sixteen votes, that the government had failed “to establish satisfactory grounds for the violent measures resorted to at Canton”. Anticipating Johnson’s Get Brexit Done election by one hundred and sixty-two years, the Prime Minister suspended parliament to appeal directly to the electorate.

In the 1857 general election, patriotic fervour was brought to bear against the Chinese rather than the EU. Palmerston declared that the problem with those who criticised the war on China was that “Everything that was English was wrong, and everything that was hostile to England was right”. Amid complaints of creating an “artificial public opinion”, the prime minister solicited the cartoonist George Cruikshank to circulate images of Chinese methods of torture and execution and fabricated a story that British heads had been displayed on the walls of Canton. It was printed in The Times and other evening newspapers and distributed as a flyer across Britain. In the midst of what Charles Greville called the Prime Minister’s “enormous and shameful lying”, Palmerston won a landslide victory. Many of his opponents lost their seats. All thanks, the Daily News claimed, to “the excited ignorance of a misinformed public”.

If Palmerston had not opportunistically seized upon the mid-nineteenth century culture war to portray activists of colour and their white reformist allies as woke threats to the nation, perhaps China’s Century of Humiliation and ensuing determination to reassert itself against global western domination might have taken a different direction. If key figures like Carlyle and Dickens had not entrenched British racism in the wake of emancipation, then perhaps we might have fewer of the structural issues that today’s antiracist “woke” activists are still having to combat. Who knows, given the speculative nature of counterfactual history? Perhaps the greatest irony, however, is that today’s conservative culture warriors, in pressure groups like Restore Trust, now claim emancipation from slavery and humanitarian concern for the welfare of colonised people as Britain’s greatest imperial achievements.

Professor Lester’s article is predicated on the assumption that the legacies of the British Empire are all negative and anyone who thinks otherwise must be of the Tory right. He may be surprised to learn that many of us who have lived or are living in Britain’s colonies are more than happy to mention the positive legacy of the British era. This is not surprising as we have seen with our own eyes the schools, the hospitals, the law courts and the parliaments which the British bequeathed to our countries which most people in the UK have never seen.

He may also be surprised to learn that the Sri Lankan press frequently mention the positive British legacy. The following link contains about a dozen articles published recently in Sri Lanka in their most respected newspapers on subjects varying from schools, hospitals, governance, railways, tea industry and museums.

http://www.forgotten-raj.org/doc/colonial_nostalgia.htm

If anyone wishes to understand the British legacy, I would urge them to go to the former colonies and see these establishments for themselves and not rely on what is presented in the media and academia in the UK.

Actually the article is not premised on the idea that the legacies of the British Empire are all negative. Reading it should help clarify that. Neither, of course, are the legacies all positive. The question is, negative or positive for whom?

By positive and negative legacies, I mean for the colonised people ie the local population.

The second sentence of your paper is:’ A key plank of the strategy has been attacks on those who attempt to educate and inform the public about racial discrimination and legacies of the British Empire’. I understood from this that the legacies you are referring to a negative ones like racial discrimination. Indeed in the paper the only legacies you mention are negative ones such as slavery, racism, opium trade and military excesses. If I have misread your paper and by legacies of empire you also mean positive ones for the colonised, why are they not mentioned in the paper?

The sentence refers to the fact that the only legacies questioned by conservative culture warriors are those of racism, discrimination, violence etc. Of course they wish to defend the well-established tradition in Britain of highlighting legacies that benefitted certain other groups. If your argument is that certain colonised people benefitted too from British colonialism, of course they did, even if the institutions that they helped British rulers to run discriminated against them on the grounds of their ‘race’. There’s so much proper historical research on the nuances of colonial rule in practice it’s difficult to know where to begin and well beyond the scope of this blog, which was about the culture war here in the UK. My own latest research, which explores these nuances, is here if you’re interested: https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/ruling-the-world/6264B85460CE672609666F24F86EBEFD#

The primary origin of current “woke” can be meticulously documented from the US New Left espousal six decades ago of a “race, gender, class” revolution against existing western social structures, and the enlistment of “women, students, blacks, migrants & sexual minorities” for that purpose, and the spread of this ideology through Critical Studies and the incremental ideological colonisation of educational and government facilities, with increasingly obvious orchestration of policies and terminology as “diversity, inclusion, eq[ual]ity.”

Its very interesting how you see civil rights and feminism as ‘a revolution against existing western social structures’, rather than tendencies reflecting the virtues of western democracy. It suggests the western values you want to retain are those before Black people and women had the vote?