flickr photo by Drew Avery shared under a Creative Commons (BY) license

A major challenge facing the adoption of new ideas and innovative practices is that of overcoming existing socially created dispositions and values or, as Derek Robertson from the University of Dundee put it in his recent seminar on games-based learning here at Sussex, “…the inexorable glacial march of the habitus of formal established educational structures”.

The glacial like pace of (higher) educational change is particularly notable in the context of open education. Whilst technological innovation – most notably the development of the social web – and the politically driven reforms stemming from the recommendations of the Finch Report (2012) have in a relatively short space of time disrupted traditional patterns of academic publishing, the same cannot necessarily be said for open educational resources (OER) and in the broader sense open educational practices (OEP).

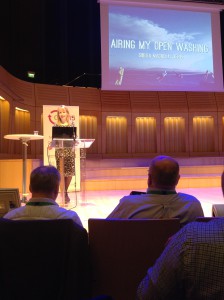

“the notion of openness can for some…seem scary” (Sheila MacNeill)

A recurring theme of the recent OER15 conference was the need to enhance recognition of the benefits of OER within teaching and learning. This was summed up by speaker Paul Bacsich who highlighted that despite 10+ years of the OER movement, uptake among teachers and students remained low. Perhaps this is unsurprising. As Sheila MacNeill put it in her keynote the notion of openness can for some – particularly those in senior management concerned about reputation, growth and competitive edge – seem scary and ‘deciding how open you want, or indeed can be, takes time’. Fellow keynote speaker Cable Green called for the development of a more open culture in higher education and argued forcefully that publicly funded educational tools and resources should be openly licensed and freely available for others to access, use and remix. It is hard to see how, without a Finch like set of reforms and an accompanying lever such as the REF, recognition, use and perceived value of OER will gain greater traction in an educational landscape with ingrained norms and expectations.

There are however rays of hope. A number of universities, such as the University of Leeds, are setting up working groups and establishing institutional policies on use of OERs and the ability of staff to apply open licences to work they produce. Beyond the HE sector the excellent work of Josie Fraser and Leicester City Council shows how capacity can be built and how this can enrich digital practices.

The Diglit Leicester project has resulted in the development of OER guidelines across 23 schools and the granting of explicit permission by Leicester City Council for staff at community and voluntary controlled schools to open licence educational resources produced in the course of their employment. The impact and implications of this project represent more than a glacial march, they are arguably representative of a seismic shift which will hopefully ripple across the education sectors.

The freedom conferred to teachers by Leicester City Council will hopefully help foster further innovation in open teaching practices. The development of similar policies within HE (or a consistent, sector-wide framework) would potentially empower similar freedom among academics and students. At the University of Sussex, the Technology Enhanced Learning team working alongside colleagues in the Library, will continue to champion the cause of open. Our immediate challenges are to raise awareness of Creative Commons licensing and issues relating to copyright. We must also help colleagues see the benefits to be gained from teaching and researching openly and help them to locate the many valuable openly licensed resources that are out there that can enrich their teaching and their student’s learning.

We will crack open education. The march may be glacial but it is undoubtedly inexorable.

[…] Read the full story by University of Sussex Technology Enhanced Learning Blog […]