Kemi Badenoch, The Institute of Economic Affairs and the Distortion of Colonial History[1]

Alan Lester

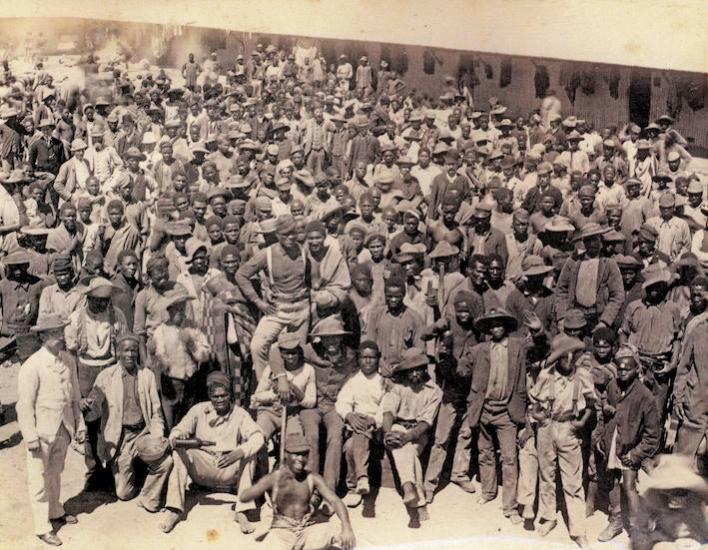

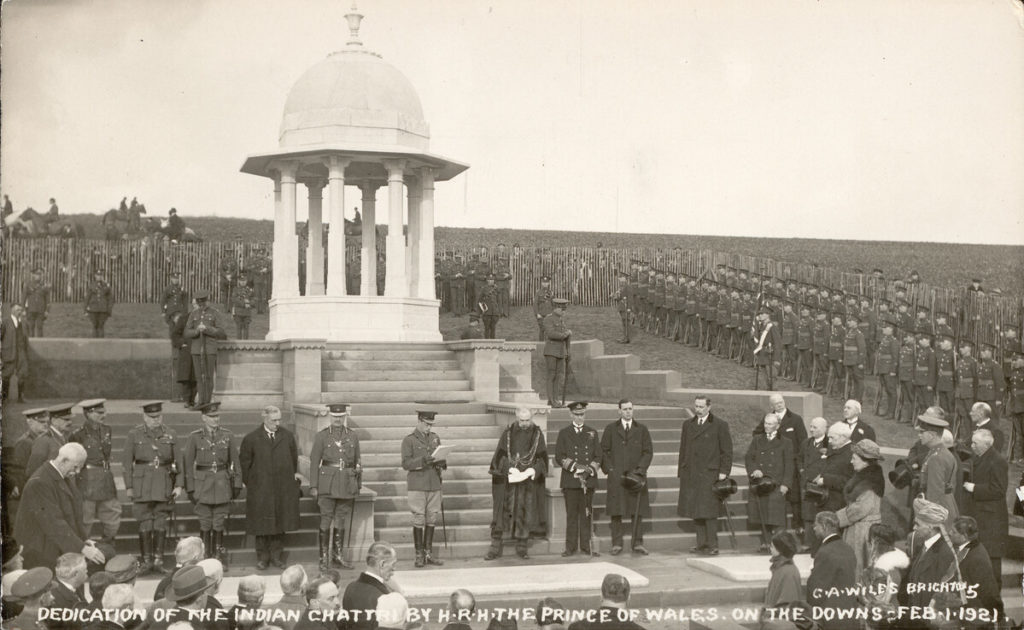

De Beers African Migrant Labour Compound, c.1886

The IEA (Institute for Economic Affairs) was last in the news when its advice informed Liz Truss’ and Kwasi Kwarteng’s disastrous mini-budget. Now it is back, lending its intellectual heft to Truss’ possible successor as Tory leader, Kemi Badenoch. The Business and Trade Secretary has made a series of public interventions in recent months, attempting to defend the British Empire from critique and IEA’s Head of Political Economy, Dr Kristian Niemietz has launched an obliging 70 page book, Imperial Measurement: A Cost–Benefit Analysis of Western Colonialism. It claims that slavery and colonialism made little difference to, and were possibly even counterproductive for, Britain’s economic growth. Badenoch immediately drew three contemporary ‘lessons’ from its ‘findings’: that the ‘UK’s wealth isn’t from white privilege and colonialism’; that the call for reparations to former colonies is based on a misunderstanding and will only ‘make all of us – not just in this country, but around the world – poorer’; and that ‘if developing nations do not understand how the West became rich, they cannot follow in its footsteps’.[2] At the same time, Imperial Measurement received widespread newspaper coverage including acclaim from The Telegraph. In The Times, Rod Liddle hailed Niemietz as an expert historian, to whom we should all pay attention.

Badenoch’s speech, the IEA book launch and the conservative press coverage seemed suspiciously synchronised – perhaps an example of the orchestration between Tory politicians, obscurely funded Tufton Street think-tanks and right wing media that has become routine over the last decade or so. Even the Daily Mail noted that ‘Mrs Badenoch … made a similar intervention on the subject earlier this month as she tries to woo grassroots Tories.’ Nonetheless, Imperial Measurement is likely to continue popping up in various guises. It will no doubt be cited as historical ‘evidence’ underpinning rebuttals of social justice and reparations claims. In this blog I consider how its claims measure up in the light of decades of more disinterested, specialist research.

Points of Convergence

Just because Niemeitez seems to be coming at history with a contemporary political agenda in mind, it does not mean that everything he says is wrong. There are points where his findings converge with the academic consensus.

He is quite correct to point out that the economic data sustaining any putative cost-benefit analysis of the British Empire is patchy. The figures we have even for trade and capital investment rates, which are Niemietz’s main preoccupations, tend to be guestimates. There are particular problems if the researcher’s motivation is to isolate one source of investment income, such as that from colonial activities, from all other sources in order to assess its relative contribution to crucial investments in Britain. Many of the individuals and families investing in textile factories, mining and railways, for example, had interests in both domestic agriculture and colonial enterprises and we are unable to conduct the forensic accounting required to follow the trajectories of specific sums of money. The fact that there are far more unknowns than knowns when it comes to economic history gives rise to debates that will never be resolved satisfactorily, even when all those engaged are acting in good faith. We should also bear in mind that, in any case, not all of the impact of colonialism and empire is measurable in quantitative, monetary terms. Kemi Badenoch herself made that point, perhaps unwittingly, when stressing the effect of institutional and political changes after the Glorious Revolution of 1688.

Aside from agreeing with Niemietz on the uncertainties surrounding any cost-benefit analysis, I am in accord with two more of his arguments. First is his declaration that ‘when the National Trust decided to publish its Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties … this was not an exercise in performative “wokery” or self-flagellation. It is part of the history of those estates, and there is nothing wrong with acknowledging that.’ Given that the IEA is often linked with Restore Trust, the private company that has teamed up with the Telegraph to launch a sustained and often ridiculous attack on the National Trust, this admission from Niemietz may seem surprising. We should bear in mind, then, that the IEA is associating with Badenoch more in support of her free market orientation than her culture war provocations.

Finally, Niemietz is refreshingly frank in admitting that, whatever its costs and benefits to Britons, ‘colonialism left significant economic and political scars on former colonies by leaving behind corrupt institutions’. Badenoch, who consistently denies such colonial legacies, will again have to engage in some cherry-picking when she invokes his book.

Unfortunately, I found little else to agree with in Niemietz’s cost-benefit analysis. It seems to be motivated by the desire to challenge Black Lives Matter and so-called ‘woke’ culture, rather than any genuine curiosity about the role of colonialism in British economic history.

The Straw Man

Niemietz gets underway by setting up a straw man.In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement, there is, apparently, a public ‘narrative in which colonialism and slavery are … the very foundations on which the Western world’s wealth – and Britain’s in particular – was originally built.’ Niemietz concocts the term Marx-Williams thesis to denote this supposedly influential narrative. This ‘thesis’ is derived by melding a partial understanding of Eric Williams’ book Capitalism and Slavery with Karl Marx’s declaration that ‘capital comes dripping from head to foot, from every pore, with blood and dirt’. Having invented the thesis, Niemietz asserts that ‘What we have seen since 2020 is an extension … the “BLM-isation” or “Wokification” of the Marx–Williams thesis’.

In the absence of any academic source articulating this ‘thesis’, Niemietz resorts to quotes extracted from the writings of activists, journalists and politicians that supposedly demonstrate it in action. The problem is that only one of the extracts overstates the contribution of slavery and colonialism in the manner described. Afua Hirsch comes closest to expounding the ‘thesis’, writing that ‘The proceeds from this enslavement … provided the profits with which Britain modernised its economy.’ That word ‘the’ before ‘profits’ provides Niemietz with what he is looking for.

However, all of Niemietz’s other sources narrate a more nuanced story. The member of the ‘Colston Four’, Sadiq Khan, the Labour MP Zarah Sultana and the Guardian writer Nesrine Malik say, respectively, that ‘[S]o much of the prosperity enjoyed today in the UK … comes off the back of historical atrocities’; that ‘our nation and city owes a large part of its wealth to its role in the slave trade’; that ‘[t]he wealth that enriched the British Empire … meant the murder, destruction, and brutalisation of people across the world’, and that ‘Britain’s involvement in the slave trade … explains much of why Britain … looks how it does today.’ Niemietz tells us that even the BBC’s educational resource, Bitesize, tells ‘the same story’ of ‘colonialism and slavery’ being ‘the very foundations’ of British prosperity, but it actually states only that ‘The slave trade was important in the development of the wider economy’.[3]

Perhaps most telling is Niemietz’s use of ellipses. He quotes the activist and journalist Owen Jones as writing that ‘The capital accumulated from slavery … drove the industrial revolution ….’ However, the original is: ‘The capital accumulated from slavery – from tobacco, cotton and sugar – drove the industrial revolution in Manchester and Lancashire; and several banks today can trace their origins to profits made from slavery.’

When confronted with the missing elements of Jones’ quote on X, Niemietz’s reply was, ‘Yes – so? Of course it [capital accumulated from slavery] had to come from specific sectors, and happen in specific places. Of course the effect can’t be uniformly distributed across all sectors and all places in the country. I’m cutting that out, because I’m not interested in the specific channel’.[4] That specific channel, of course, is one of the main things that his report is supposed to be evaluating, since all historians of the Industrial Revolution are agreed that it ‘was first and foremost a regional phenomenon, with growth and radical transformation occurring in clearly defined industrialising regions while other areas of the country declined or marked time.’ Niemietz’s reaction reveals, to me at least, that his interest was not so much to determine the causes of this phenomenon as to contradict anyone drawing attention to the role of slavery within it.

It is easier to find oversimplification and exaggeration in Niemietz’s own writing than in the extracts he supplies for a ‘wokified’ Marx-Williams thesis. In The Times he concludes, ‘Ultimately, what made Britain rich was not slavery or empire but the development of liberal institutions such as the rule of law, property rights and entrepreneurship’. None of the sources he quotes goes so far as to posit a zero-sum game between either colonial exploitation or domestic liberal institutions, rule of law etc. Most commentators recognise that it was some combination of internal and external stimuli including colonial exploitation that made Britain’s unprecedented economic growth possible. They appreciate that colonial expansion helped to propel the development of profit and rent seeking ‘liberal’ institutions within the UK. The development of Britain’s liberal institutions and its colonial exploitation proceeded neither in competition nor in isolation, but hand-in-hand.

It is true that we have arrived at ‘a moment in British cultural life in which the salience of slavery is at a high point’, but it also true that this novel attention follows ‘decades – centuries – of exclusion and evasion’. Even in such a short book it helps Niemietz to devote his opening pages to the construction of a straw man embodying the peril of this ‘moment’. Portraying the Black Lives Matter-inspired ‘wokerati’ as massively overstating the influence of slavery enables his dismissal of any economically-positive influence at all to seem like a moderate counterbalancing. The extremism of his own position can be hidden as a simple corrective to the extremism of others.

The Evidence

Imperial Measurement’s analysis of Britain’s colonial economy rests upon three pillars. The first is extracts from articles by economic historians, the most influential of whom is Patrick O’Brien. The second is Adam Smith’s and Richard Cobden’s analysis that the British Empire was costing most Britons more than it was returning to a small elite. The third is an attempt to counter Berg and Hudson’s synthesis of more recent research examining the long term role of slavery.

I will consider each of these three elements in turn before turning to some of the considerations that I would have expected to find in any impartial cost-benefit analysis, but which are simply not considered or are glossed over, in Imperial Measurement.

- The Scholarship

Niemietz leans heavily on two papers published in the 1980s by the respected economic historian Patrick O’Brien. The first, from 1982, is cited as showing that trade between the UK and its colonies was minimal compared with trade with the USA and other European nations, and that the investments of profits from this trade would have funded only 7-15 per cent of Britain’s overall investment expenditure.

Aside from the point that this overlooks the role of such investments specifically within the sectors driving the Industrial Revolution, O’Brien was quite clear that this article was a response to what he saw as the exaggerated claims of the dependency theorists of the 1960s-70s, including Immanuel Wallerstein, Gunder Frank and Samir Amin. Like Niemietz, O’Brien accepted ‘that restraints on the evolution of free markets for labour and impediments to the reallocation of resources from primary production to industry and urban services hindered progress towards a modern economy’ in Europe’s colonies. Unlike Niemietz, however, O’Brien also affirmed, ‘there can be no dispute that rewards from participation in foreign trade were unequally distributed during the mercantile era when military force formed an integral part of the international economic order’.

O’Brien did suggest that ‘the commerce between Western Europe and regions at the periphery of the international economy forms an insignificant part of the explanation for the accelerated rate of economic growth experienced by the core after 1750’, but cautioned that ‘the problem of determining’ its significance ‘cannot be solved until historians construct financial flow tables which reveal the sources of funds actually used to pay for the net and gross investment expenditures which occurred in Britain for a century after 1760. Since that is not even a remote possibility, the estimation of profits gained from trade with the periphery is simply an exercise to reveal potential orders of magnitude and their real significance will remain conjectural’. He proceeded nonetheless to speculate that ‘commerce with the periphery generated a flow of funds sufficient, or potentially available, to finance about 15 per cent of gross investment expenditures undertaken during the Industrial Revolution’. In itself, this is not an insignificant proportion, and if a relatively high proportion of the 15% was invested in the sectors driving industrialisation (something that I return to below), Niemietz would have little ground upon which to stake his minimalism. So he pushes O’Brien’s speculative gross figure downwards, insisting that ‘If we assumed more typical savings rates, it would have been more like 7 per cent’.

Having cherry-picked O’Brien’s 1982 paper, Niemietz proceeds to rely much more heavily on a second O’Brien paper from 1988. He quotes its conclusion:

modern research in economic history now lends rather strong empirical support to Cobdenite views of Britain’s imperial commitments from 1846 to 1914. Only conquests of loot and pillage of the kind maintained by King Leopold in the Congo seem capable of providing metropolitan traders and investors with supernormal profits. In this sense the British empire can be plausibly represented, in Adam Smith’s words, as ‘a sort of splendid and showy equipage, not an empire but the project of an empire, not a gold mine but the project of a gold mine’. Clearly the empire was an enormous fact which imperial historians will continue to puzzle over and explain. For not inconsiderable numbers of English people (outside and inside some very powerful social groups) the empire paid. What has been argued above is that massive public expenditure upon the apparatus of imperial rule and defence was neither sufficient nor necessary for the growth of the economy from 1846 to 1914.

This quote provides Niemietz with the architecture for Imperial Measurement. The book pitches the views of Cobden and Adam Smith against the orthodoxy; it identifies the Belgian Congo as a unique case of colonial exploitation paying off, and it speculates that the benefits of imperialism were shared among an elite few while the rest of the British population bore the costs.

However, each of these elements was questionable when O’Brien published this paper and even more so 36 years on. Not least as a result of O’Brien’s own subsequent work. If we survey just a sample of the findings from the 50-odd academic papers that O’Brien alone published between 1992 and 2004 as he considered new sources of evidence and engaged with the work of his colleagues, a rather different assessment emerges.

In 1992 (republished 2010), O’Brien noted that ‘after 1846 the free trade that British political and intellectual elites espoused and promoted benefitted not only Britain but the international trading system as a whole.’ Whereas the 1982 and 1988 papers did not consider the effects of the 22 million strong British diaspora that migrated during the nineteenth century to the USA, Canada, and the rapidly expanding colonies in Australasia and Africa, in a 1996 paper O’Brien argued that Britain’s pioneering industrialisation was owed in part to the ‘market for manufactures’ created by these ‘masses of British wage earners who had migrated and committed themselves to work in towns and cities within the realm and its expanding empire overseas’. In 2004 a group of economic historians published a collection of essays in honour of O’Brien’s retirement, presenting a condensed summary of the field in which he had laboured. Niemietz, and Badenoch for that matter, would have done well to consult, since it

explores the question of British exceptionalism in the period from the Glorious Revolution to the Congress of Vienna. Leading historians examine why Great Britain emerged from years of sustained competition with its European rivals in a discernible position of hegemony in the domains of naval power, empire, global commerce, agricultural efficiency, industrial production, fiscal capacity and advanced technology. They deal with Britain’s unique path to industrial revolution and distinguish four themes on the interactions between its emergence as a great power and as the first industrial nation. First, they highlight growth and industrial change, the interconnections between agriculture, foreign trade and industrialisation. Second, they examine technological change and, especially, Britain’s unusual inventiveness. Third, they study her institutions and their role in facilitating economic growth. Fourth and finally, they explore British military and naval supremacy, showing how this was achieved and how it contributed to Britain’s economic supremacy.

As Jeremy Black concludes, ‘the contributors, each in their own way, agree that eighteenth-century Britain had some special qualifications that allowed it to become “the workshop of the world” by 1850’. These qualifications were multiple and intersecting, domestic and global. They included ‘its privileged position in India and North America, and its commitment to its navy as bulwark of international trade’. Javier Cuenca Esteban’s chapter, for instance, ‘emphasizes England’s luck in its peculiar footholds in India, North America, and the West Indies, and demonstrates how land, slave labor, and cheap Indian calico production freed British labor to work in agriculture but especially in urban manufactures’.[5]

Stanley Engerman, someone upon whose other work Niemietz relies to minimise the contributions of the eighteenth century slave and sugar trades, concludes the volume with ‘a reminder that Britain did not achieve real “supremacy” until the middle of the nineteenth century, and much of this due to its empire’.

In 2022, Peer Vries analysed the overall impact and legacy of O’Brien’s work. It might make uncomfortable reading for Niemietz and Badenoch:

Patrick is clearly against specific Whig interpretations of British economic history which maintain that industrialization occurred first in Britain because it had a distinctive set of institutions, first and foremost its ‘representative’ state and its market economy … Patrick’s work has extensively and effectively demolished such theses.

Still incisive at the age of 91, Patrick O’Brien has given me permission to quote some of our private correspondence on Imperial Measurement. He said that ‘what these people do is use old research as if it is current, if it makes the points they want it to make. This no basis for an impartial assessment.’ [6] He then proceeded to tell me how he thinks a contemporary cost-benefit analysis should work:

First it would engage with two distinct historical chronologies before and after the period when GB became the world’s leading industrial economy. The first should remain focussed on connexions between colonial power and rule and Britain’s precocious transition to an industrial economy. My chronology for that narrative would close around 1850 and then I would move onto connexions between colonial power and rule from say 1850 and 1914. Today my narrative for the Industrial Revolution would contain an analysis of when, how and why Britain as a small island off the coast of Europe established a fiscal naval state first and foremost for defence against France and Holland then to protect its commerce overseas. My post 1850 analysis would concentrate on the role played by the navy for the costs and benefits of the expansion in world trade. I would deal with exploitation by looking carefully at the prices obtained for European [countries] including Britain for imports from countries and populations under colonial power and rule. Did the gains from these trades accrue disproportionately to Europeans or were they closer to the market prices that Indians, Africans and South Americans would counterfactually have obtained from the expansion of more peaceable and higher levels of world trade that Britain played a hegemonic role in expanding and maintaining?[7]

O’Brien is the first to admit that his is not the last word on Britain’s economic history. There are other plausible ways of pursuing such a comprehensive analysis. For my own part, I prefer to focus on what did happen rather than what might have happened under more or less speculative, counterfactual scenarios. But even if we accept O’Brien’s quantitative, trade-oriented, counter-factual approach, Niemietz’s application of it is clearly far from robust.

2. The “Smith-Cobden View”

Niemitetz follows O’Brien’s 1988 paper in centring two men who questioned the cost-benefit ratio of Empire in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, Adam Smith and Richard Cobden. Indeed, he frames the parameters of the whole ‘debate’ as the ‘Smith-Cobden view’ (correct) versus the ‘Marx-Williams view’ (wrong). Nowhere, however, does he indicate any awareness of the pivotal moment in imperial history observed by these two critical observers.

Adam Smith did indeed argue ‘that the British Empire enriched a small group of politically privileged traders at the expense of general prosperity’, but he was famously critiquing the mercantilist system of trade prevailing at the time. Working for the free-trade promoting IEA, Niemietz should know that this system was soon supplanted, in part due to Smith’s critique.

Smith’s argument was that the late eighteenth century empire’s

real effect has been to raise the rate of mercantile profit, and to enable our merchants to turn into a branch of trade, of which the returns are more slow and distant than those of the greater part of other trades, a greater proportion of their capital than they otherwise would have done […] Under the present system of management, therefore, Great Britain derives nothing but loss from the dominion which she assumes over her colonies.

By the 1820s that ‘system of government’ was being dismantled in order to open up the opportunities of colonial exploitation to a wider range of Britons.

Before I move on to consider what followed Smith’s critique, though, it is worth noting two aspects of that critique that Niemietz also overlooks. First, it was directed not just at those engaged in the Caribbean slavery-based economy, but on the activities of the monopolistic East India Company in the Indian Ocean. Smith described the Company as the body ‘for the appointment of plunderers of India’. He was referring to people like H. St George Tucker whom George Prinsep quoted in 1821: ‘I could only give a vague estimate of the amount of this indirect or private tribute’ from Bengal, ‘which very much resembles the rents and profits drawn by British proprietors from the sugar plantations in the West Indies; but it is unquestionably considerable, and I am disposed to think, that it cannot fall short of three millions sterling per annum at the present period.’[8] The abolition of the Company’s monopoly on trade with India in 1813 and on commerce with the East in general in 1833 were all part of the free trade-oriented reforms for which Smith agitated, intended to open up India’s resources and markets to a wider range of British investors.

Secondly, Smith, who died in 1790, could not have been aware of the longer-term implications of the investments being made within his lifetime. By no means a majority of the mercantile elite’s wealth was invested in activities that would, in retrospect, be seen as having helped kickstart Britain’s Industrial Revolution (as we can see from their country houses), but some of it was. According to the pioneering work of Joseph Inikori, in 1770, the slave trade and the plantation economy was furnishing as much as fifty-five percent of gross fixed capital formation investment in Great Britain. East India Company stakeholders were similarly engaged in investments the significance of which would become clear only in the coming decades. The Prinseps, for example, were able to participate in the railway mania of the 1830s-40s because of the wealth generated from the plunder of Bengal that George had noted in the 1820s.

Individuals and families who profited from the slavery-business to the West and the East India Company to the East were investing in sectors that later became central to Britain’s economic dominance even as Smith was arguing for a deeper cross-section of British society gaining access to the opportunities of colonial exploitation.

William Huskisson may be most famous today for becoming the first person to die in a train accident, when he was run over by Stephenson’s Rocket in 1830, but he should be better known for his contribution to British and imperial history. After co-authoring the report with David Ricardo which laid the intellectual groundwork for scrapping the Corn Laws, he took Smith’s advice to nudge Britain and its empire away from the labyrinthine system of tariffs and preferences and towards freer trade. As President of the Board of Trade, Huskisson appreciated that a more liberal trading regime, cast widely across the world, would benefit more Britons as the country transitioned into an industrial powerhouse. His realisation was grounded not just in his appreciation of Smith’s writings, but also by his background as the London-based agent for British colonial interests in the Cape Colony and Ceylon. The latter’s coastal plantations, he wrote, could well become a ‘small spearhead of the imperial economy’, supplying primary produce that British manufacturers could turn into profitable exports, if only ‘our ancient colonial system’ of trade regulations could be reformed.

William Huskisson by Richard Rothwell, 1868

Through the 1820s, Huskisson’s Board of Trade repealed over 1,000 separate customs acts. It also began to mitigate the Navigation Acts, which had prevented direct trade between different British colonies and barred them from trading with foreign nations’ merchant ships. Huskisson remained a pragmatist though. Free trade for him was no doctrinaire ideal but rather a strategy to be applied only where favourable to Britons. For instance, he retained imperial preference for Canadian timber and corn imports to boost British settler entrepreneurialism against French-speaking influence. As his biographer concludes, ‘Huskisson was par excellence an “imperial statesman” with a vision of Britain as the dynamic centre of an expanding colonial horizon, with empire offering tangible economic and political resources to the British state’.[9]

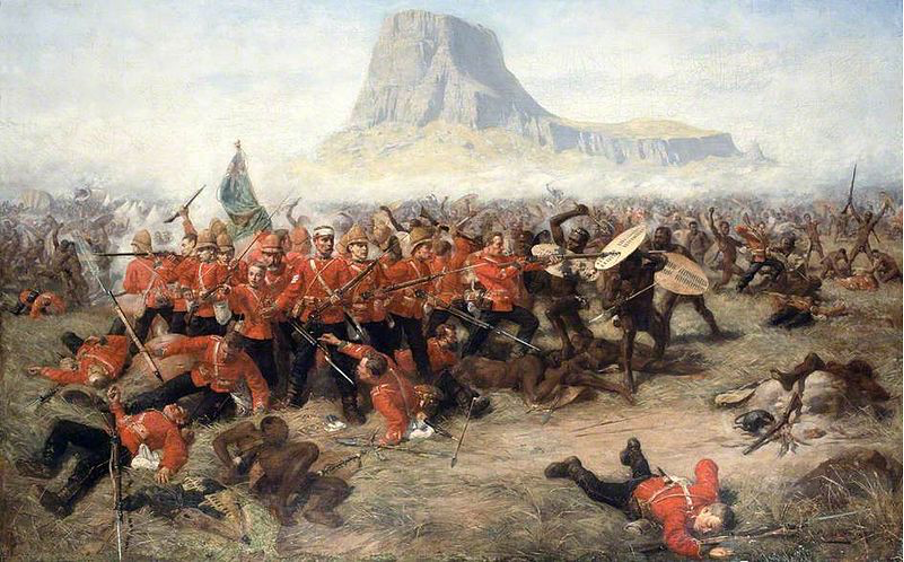

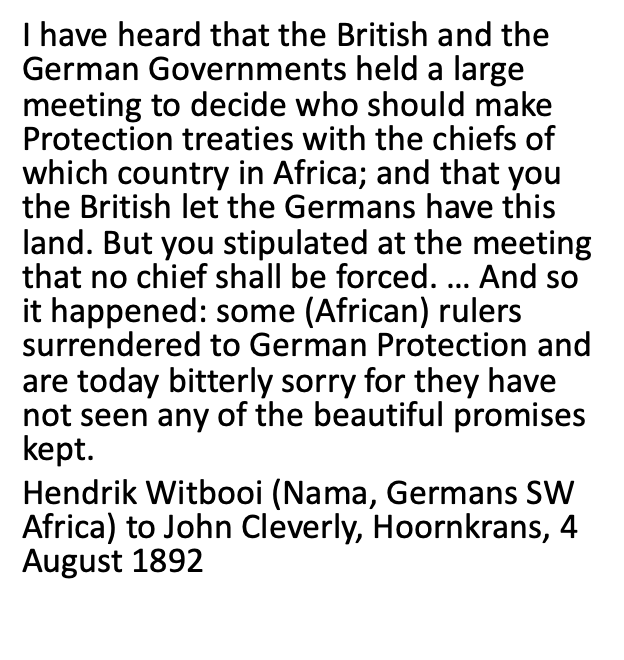

Although Smith died at the beginning of the Huskisson-led transition that he had helped to inspire, Cobden lived to witness many of the developments succeeding it: developments that go largely unacknowledged in Niemietz’s analysis. From the 1830s, the British Empire underwent an enormous expansion and reorientation. What specialist historians call the ‘First British Empire’ of mercantilist colonialism in the West and East Indies came to an end. The ‘Second British Empire” of c.1840-1900 looked very different.

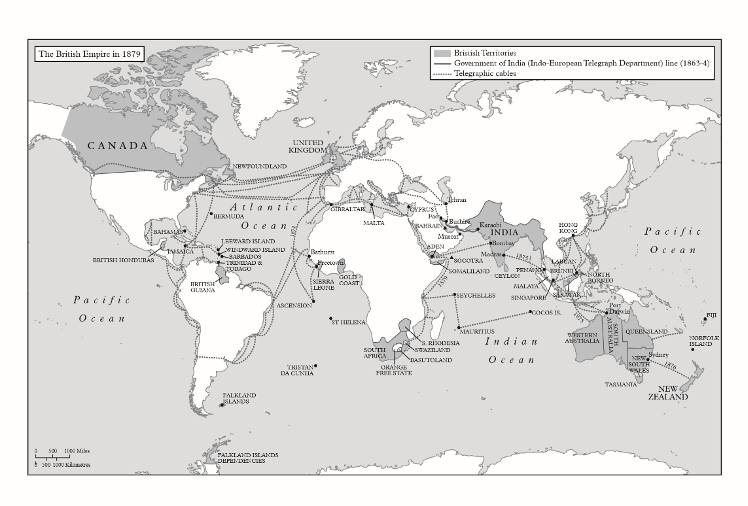

The British Empire in 1879, from Alan Lester, Kate Boehme and Peter Mitchell, Ruling the World: Freedom, Civilisation and Liberalism in the Nineteenth Century British Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2021.

No longer based on slavery in the Atlantic and monopolistic East India Company trade and governance in the Indian Ocean, this revived and expanded empire was founded on the indentured servitude of Indian subjects, the mass displacement and appropriation of Indigenous peoples’ lands in North America, Australasia, Southern and Eastern Africa, commercial crop production in Southeast Asia and the consolidation of the Raj in India. Within it, British manufacturers had access to markets skewed by colonial rule and gunboat diplomacy well beyond the formal empire. British investors had preferential access, backed by force, to resources such as diamonds and gold in South Africa, rubber and tin in Malaya, palm oil in Nigeria and, towards its end, oil in the Middle East. Smith and Cobden could only have dreamed of all this. Their view of the mercantilist empire of c.1770-c.1840 bore about as much relation to the late nineteenth – early twentieth century empire as that of Neanderthals on urban living.

The widening of opportunity for Britons to profit from this second empire shifted its cost-benefit distribution. The nominally ‘free’ trade that characterised the British Empire of the nineteenth century meant that it was no longer a case of the masses paying for the extravagant exploitation of just a tiny elite. Within Britain, the working classes did not unequivocally gain from the Industrial Revolution that mercantilist elites had helped to kickstart until the 1840s or so. Wages lagged behind prices and excise taxes were high and regressive. But investments and freer economic activity by a wider range of Britons in colonialism and empire both increased the wealth of elites and created new elites thereafter, not least the emigrants fanning out from Britain in their multitudes to settle on Indigenous peoples’ land and, often, to utilise their labour. These emigrants amounted to over 22.6 million between 1814 and 1915, the largest share to the USA but others to Canada, Australia, southern Africa and New Zealand. Many considered themselves part of the British diaspora until the early twentieth century, even if their newfound wealth was generated outside of the British Isles. As we have seen, O’Brien later assessed their significance for Britain’s economy, as both producers and consumers. Overall, the proceeds from post-1840 imperialism redistributed National Income towards those with a greater propensity to invest. Domestic consumption held up because of the buoyant incomes of the ‘middling sort’, not necessarily because working people were generally richer, but because a much larger proportion were becoming wage earners.[10]

Smith and Cobden are useful to Niemietz’s argument because they argued that the costs of protecting imperial monopolies on behalf of elites outweighed the benefits to ordinary Britons. Even at the time, however, they were unable to consider the extent to which these elites were investing in activities that would come to define the Industrial Revolution. Relying on them for an assessment of the British colonial economy thereafter is like completing the analysis of a football match at half time, before the manager makes the decisive substitutions.

3. Berg and Hudson

Niemietz has to tread carefully around the recent book by Maxine Berg and Pat Hudson, since it is a ‘rounded examination’ of the contribution of slavery to Britain’s Industrial Revolution and to the nature of British capitalism thereafter ‘in the light of accumulated research’.[11]

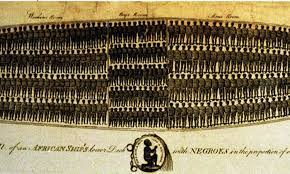

The book sets out in condensed form why there is now a consensus among experts that the ‘slave and plantation trades were the hub around which many other dynamic and innovatory sectors of the economy pivoted’.[12] Berg and Hudson explain that ‘the key manufacturing regions of the industrial revolution relied on access to Atlantic port cities, principally Liverpool, London, Glasgow and Bristol, and to the capital and credit that they generated … the qualities of raw cotton from Caribbean plantations aided the product revolution and hastened the great spinning inventions of the jenny, the water frame and the mule. These developments long predated the better-known connection between Lancashire cotton factories and the slave plantations of the American South … Plantation investment and shipping also brought innovation in the mortgage and insurance markets, in multiplex financial transfers and in the expansion of commercial credit that linked provincial merchants, manufacturers and banks with the resources of the London money market’.[13]

The Atlantic slave-based economy thus helped to fuel Britain’s industrial revolution, although it is impossible to quantify exactly how much relative to other factors.[14]

Berg and Hudson avoid the inflated claims that Niemietz’s straw man would make. He is forced to admit that ‘we do not have the expertise to pick a side in [the] debate’ on whether ‘slavery was a “strategic industry” that created positive spillover benefits for other industries’. This is, of course, a major problem or his intended overarching cost-benefit analysis. Anything to do with institutional change or innovations, the impact of which cannot be measured in the speculative and limited financial analysis upon which he relies, is necessary excluded. The best case Niemietz can make is that Berg and Hudson do not acknowledge sufficiently the costs of the military activity that maintained Britain’s dominance of the Atlantic economy. Even here though, he is on thin ice, since Berg and Hudson specifically note, based on greater familiarity with the scholarship, that ‘The “cost” of colonial defence was […] largely offset by the […] stimulus it created for the economy, in the demand for munitions, ships, ships’ provisions and uniforms’.

Niemietz lacks the data and expertise to assess what the costs of maintaining slavery were and what benefits other than the protection of the plantation economy they allowed (such as the settlement of North America or the enforced commerce from other colonial sites), so he is reduced to speculate, one senses more in hope than conviction, that ‘Once we subtract the fiscal cost, the net gains may well have been negative’. [15]

Niemietz’s final attempt to deflect from Berg and Hudson’s insights is to argue that ‘the indirect benefits of slavery … – the impact on finance, corporate governance, agronomics, etc. – are also, ultimately, domestic institutional factors, even if they had an external stimulus. At that stage, the argument is no longer that slave money financed the Industrial Revolution. It is that slavery indirectly triggered domestic institutional changes in Britain, which later made Britain more productive – a very different argument’. But not even the conjured up, fanatical adherents of the ‘Marx-Williams’ thesis are supposed to have suggested that it was only ‘slave money’, rather than the broader effects of slavery, that financed the Industrial Revolution. No wonder Pat Hudson despairs that ‘there is no cost benefit analysis in the book despite its title, no new data, no attempt to go beyond the old and misleading measures and debates, nothing. Coupled with this, the cherry picking of quotes, the distortion of arguments and the sly elision between several completely separate issues … I get bored reading this stuff because it has no claim to be considered objective or professional history’.[16]

The Omissions

It must be clear by now that there is a lot missing from the IEA’s balance sheet of empire. In fact, most of the empire, most of the time and most of the relevant literature. You would not know it from this book, but there have been hundreds of books and articles over the last twenty years on the ‘Great Divergence’ – what it was that enabled Western Europe to grow its economy so rapidly, relative to Asia especially, during the modern colonial period. As Prabir Bhattacharya explains, plenty of scholars have focused ‘on various forms of colonial extraction (including on the interactions between colonial extraction and domestic institutions)’, but in an especially important contribution, Kenneth Pomeranz ‘went beyond the usual arguments … to argue that access to coal and the “ghost acreage” that Europe derived from the New World were of critical importance. “The slave trade and other features of European colonial systems” in the New World “enabled Europe to exchange an ever-growing volume of manufactured exports for an ever-growing volume of land-intensive products … Together, coal and the New World allowed Europe to grow along resource-intensive, labour-saving paths (in contrast to the core of East Asia’s economy which was forced along labour-intensive, resource-saving paths that led to an ecological impasse)”’.

This is why the second British Empire that Smith and Cobden never lived to see is so important. ‘As Mokyr (2003) has pointed out, “the key point is that growth was sustained in Western Europe after the Industrial Revolution, instead of petering out, as in the previous episodes of growth, and that the gap in income between Western Europe and Asia had become huge by 1900”’.[17]

Even the most rudimentary cost-benefit analysis of empire should have engaged with the widespread recognition that colonial rule enabled Britons to access ‘the surplus-producing and taxable capacity of the peasants and artisans’ of tropical regions. As the economic historians Utsa Patnaik and Prabhat Patnaik explain, these colonised subjects ‘could be set’ by their British rulers ‘to produce more tropical (and subtropical) crops like cane sugar, rice, tapioca, and spices; stimulants like coffee, tea, cacao, and tobacco; vegetable oils like groundnut, linseed, and palm oil; drugs like opium; raw materials like indigo, jute, sisal, and cotton [and rubber in Malaya]; and cut more tropical hardwoods (teak, mahogany, rosewood, ebony) from the forest or from timber plantations—all goods that could never be produced in cold temperate lands’.

Colonial rubber tapping in Malaya, Early Twentieth Century

The kind of trade figures formerly examined in isolation by scholars such as O’Brien might take into account the flow of such commodities to Britain, but they hide the ways that Britons obtained them so cheaply, and how they could harness the profits of their re-export at the expense of colonised subjects. [18] This is partly why O’Brien would posit a different approach today, in the light of new research.

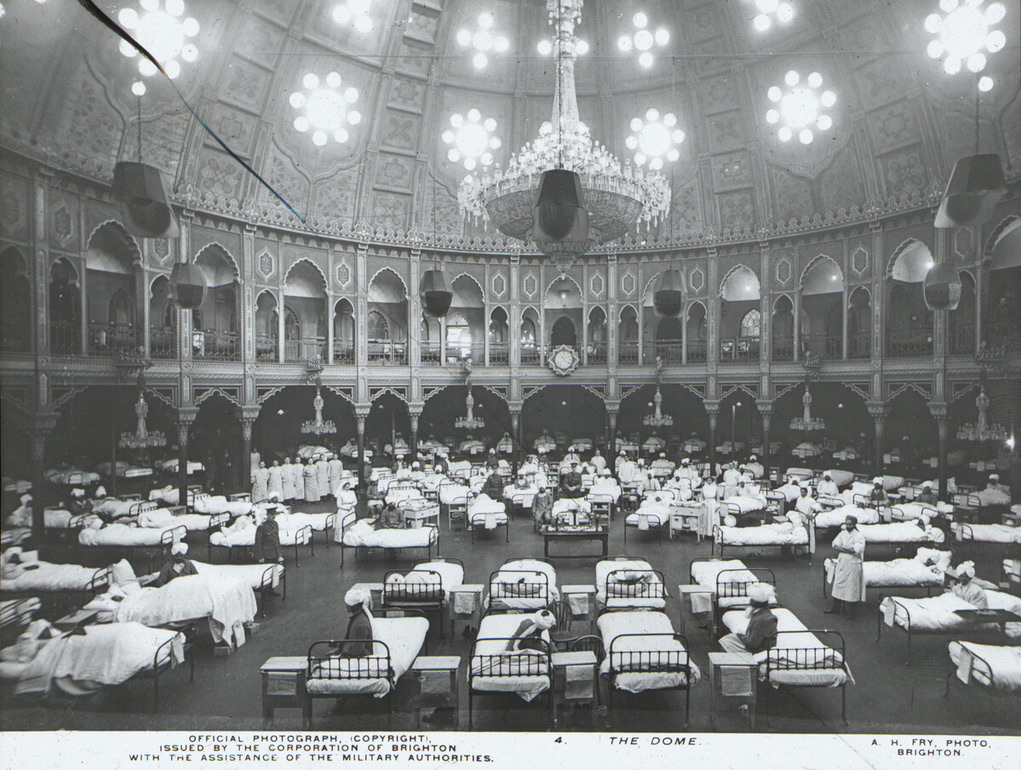

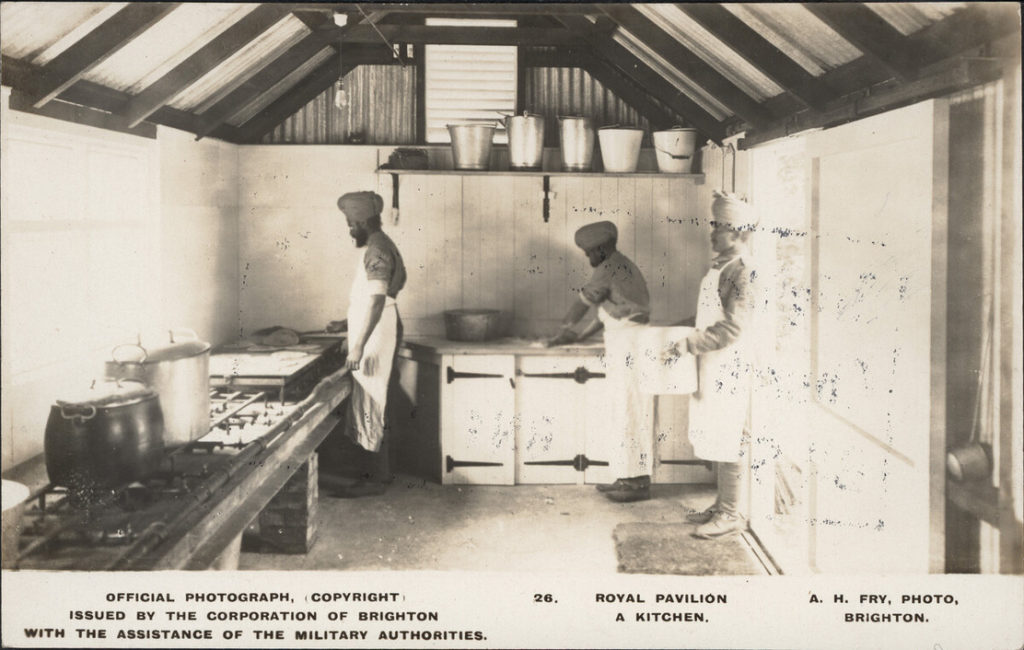

It is astonishing that, in an overall cost-benefit analysis of British colonialism, Niemietz pays so little attention to the British control of India, given that it was so crucial for the nineteenth century imperial economy. He engages with it mainly on p. 22, where the analysis consists of speculation that just as much trade might have been conducted with it even without British rule. As Battacharya notes though, ‘India’s direct contributions to … British economic development’ were multi-faceted. They included ‘the transfer of wealth from India to Britain; the role of the Indian army in furthering British economic, military and political interests; the role of India as a ‘captive’ market for British goods; the role of India’s China trade in furthering British economic development and global influence; and last, but not the least, the role of India as a source of labour for other British tropical colonies.’ There is space here to elaborate on only a few of these contributions.

The most fundamental point to note is that because they governed, rather than merely traded with Indians, Britons could charge Indians rent and use it to buy their produce. Indian farmers and manufacturers were effectively paying British rulers to take what they produced. The British could then sell that produce, mainly cotton, opium and textiles, overseas, retaining the profit. ‘Home Charges’ were also taken out of the taxes paid by Indians and sent back to Britain. These were nominally to cover certain costs of governance, including the pensions of British officials retiring home, but over 70 per cent were effectively subsidies for Britain’s military campaigns, alleviating British taxpayers of much of their cost.

In 1840 Montgomery Martin estimated the overall flow of capital from India to Britain through such measures between 1803 and 1833 alone at £724 million, noting that such ‘a drain even on England would soon impoverish her’. Some years later, George Wingate wrote that ‘The tribute paid to Great Britain is by far the most objectionable feature in our existing policy. Taxes spent in the country from which they are raised are totally different in their effects from taxes raised in one country and spent in another.’[19]

At the opposite end of the political spectrum from Badenoch, the Indian politician Shashi Tharoor, has invoked Patnaik and Patnaik’s calculation that the overall drain from India to Britain up to 1938 was in the order of $45 trillion.[20] The two economic historians arrived at this figure by estimating the import surplus into Britain from Asia. According it a present value at 5 per cent interest rates, they later updated the figure, arguing that “cumulated up to 2020, it is $64.82 trillion … much higher than the combined 2020 GDP” of the United Kingdom, the United States and Canada. Slightly different assumptions and estimates, however, lead to widely varying cumulative figures and I am inclined to take all such cumulative estimates with a pinch of salt.

Like most other historians of empire, however, I am not inclined to ignore the fact of a drain from colony to metropole entirely. [21] Most economic historians now accept that this drain ‘enabled Britain to liquidate its foreign debt in critical years before the French wars’ and ‘helped Britain to generate a current account surplus necessary for foreign investment’. In his analysis of the East India Company, Nick Robins writes, “Crucially, from 1800 onwards the Asian drain began to match the enormous extraction of wealth that Britain had historically achieved from the slave-based sugar plantations of the West Indies. Together, the combined surplus in 1801 was equivalent to over 86 per cent of Britain’s entire capital formation from domestic savings.”‘ [22]

India also contributed to a form of tax relief for Britons that should have figured in Niemietz’s speculation of who bore the costs of empire. Against his speculation that British taxpayers subsidised the imperial project, we can set the evidence of Richard Temple, who presented the ‘General Statistics of the British Empire’ to the Royal Statistical Society in 1884. He noted that of the £203 million at the disposal of the British state for general government within the United Kingdom, £89 million came from the UK itself (including Ireland), £74 million from India, and £40 million from territories and colonies in the rest of empire. Charging Indians rent relieved Britons from paying many of the costs of subordinating other peoples around the world. Indian troops under British command, paid for by Indian and not British taxpayers, served in China in 1839, 1856, 1859 and 1909, Persia in 1856, Ethiopia and Singapore in 1867, Hong Kong in 1868, Malaya in 1875, Malta in 1878, Afghanistan in 1838 and 1878, Egypt in 1882, Burma in 1885, Nayasa in 1893, the Sudan and Uganda in 1896, South Africa in 1899 and Tibet in 1903. The enforcement of opium trading in China alone enabled import duty revenue from Chinese tea equivalent to two-thirds of the UK government’s average annual expenditure on the navy or about half of the average annual expenditure on “Army and ordnance” between 1835 and 1858.

One might expect someone trying to weigh up the empire’s costs and benefits to pay some attention to those who weighed up the costs and benefits at the time. Even if Niemietz might be inclined to declare that they got it wrong, consistently over some three hundred years, one might expect an explanation of why they were quite so persistently idiotic. But Niemietz pays no attention whatsoever to imperial governance. From the early nineteenth century, in part following Smith and Cobden’s critiques and Huskisson’s reforms, the British government required Blue Books of each colonial governor. Their purpose was to tally up the costs and benefits of maintaining each colony. The different departments of imperial governance each conducted their own periodic surveys, using these books and directed correspondence with governors, to see how that balance was working out.

In 1860, for instance, the War and Colonial Offices broke down military expenditure by each colony to see what ‘bang for their buck’ was being attained by each component part of the Empire. Niemietz could have looked at such correspondence or even just at the numerous publications of historians on it. The governor of the Cape Colony, George Grey, was told for instance, that although he was absorbing nearly a third of the empire’s military resources in his attempts to dispossess Xhosa people, the policy was working for the benefit of only a few thousand British settlers who craved more of the amaXhosa’s land than they had already appropriated. Grey was told that his job was to think about the greater good of Britain and recalled as a result.[23] Such an example, plucked out of context, would have suited Niemietz’s purposes nicely. What it demonstrates though, is that colonial administrators were not just stupidly pursuing policies that consistently did Britain more financial harm than good.

Finally, if Niemietz was serious about understanding scholars’ discussions of the imperial economy as a whole, one of his standard sources should have been the multiple volumes in the Oxford History of the British Empire. This was published in 1999, well before the supposed ‘great Awokening’ but after the cited O’Brien articles. Most of the economic historians who contributed, including O’Brien himself, would be considered conservative. None came even close to peddling ‘the historic emphasis that we would expect in an age of woke anti-capitalism.’ These economic historians were commissioned to provide precisely what Niemietz was supposedly looking for: a summary of how the Empire contributed (or not) to Britain’s economy.

For the eighteenth century, O’Brien concluded ‘very few critics of mercantilism and Imperialism writing between 1688 and 1815 developed an alternative blueprint for national development that might have carried Britain to the position within the international order that the country occupied when Castlereagh signed the Treaty of Vienna. Nearly everyone at the time perceived that economic progress, national security, and the integration of the kingdom might well come from sustained levels of investment in global commerce, naval power, and, whenever necessary, the acquisition of bases and territory overseas’. For the nineteenth century, Peter Cain concluded, ‘In effect, Britain paid its growing debts in Europe and America with credit earned in the newly settled and underdeveloped world, a large part of which was within the Imperial domain.’ David Fieldhouse, whose work Niemietz leans on for his very brief account of the French Empire, wrote of the twentieth century: ‘overall, then, it would seem that the Empire made a significant, if ambiguous, contribution to the British Economy in the twentieth century … it remains quite unclear how Britain might have prospered without her Imperial crutches after 1914’.

Conclusions

Niemietz concludes that “To find even modest positive effects” of empire,

we have to make a series of debatable assumptions that are biased in favour of the Marx–Williams hypothesis. We have to assume that Britain’s administrative and defence expenditure was largely fixed, and that there is no huge cost difference between governing an island in the North Sea and governing a globe-spanning empire. We have to assume that the vast majority of the economic transactions that happened under the political structure of colonial rule happened because of that political structure, and could not have happened otherwise. And even then, we have to assume that the British economy was rigid and inflexible, unable to find substitutesfor colonial imports or alternative uses for the resources it deployed in connection with the colonies. We have to assume that slave traders, plantation owners and colonial entrepreneurs were exceptionally frugal people who invested unusually high proportions of their profits.

We do not have to make any such assumptions. We need to approach the existing scholarship with an open mind and a determination to engage with as much of it as possible.

Had Niemietz have done this he might have reached something like the conclusion of the latest academic paper to weigh in on the issue. ‘Whether or not slavery was necessary to the British industrial revolution is asking the wrong question, particularly when invoking the kind of explanatory “necessity” yielded by natural science experimental methods or by playing with imaginary counterfactuals. Instead, the different varieties of historical capitalism that actually developed are what need to be explained … This also means embracing a perspective of the long term, not only the inception or take-off of the British industrial revolution, but also its subsequent sustained growth’.[24]

It is indeed ‘possible’, as Niemietz speculates, ‘that a non-imperialist Britain could have enjoyed most of the gains from the Empire while avoiding most of its costs’. And it is true that ‘If so, non-imperialist Britain would have been richer than the one we live in.’ It is also possible that Britain might have been colonised by Martians. Neither of these things happened. Britain did become an imperial power, its economic development did proceed hand-in-hand with various forms of colonial exploitation, including but not restricted to slavery, and the exploitation of other places and people did contribute significantly to its wealth. Whenever and wherever governmental imperatives facilitated it, Britons proved just as capable, if not more so, of enriching themselves with the land, resources and people of their colonies as the representatives of any other empire have done through recorded history. It should not need pointing out, but it is no coincidence that the wealthiest societies in history tend to be those at the centre of great empires.

There has been no ‘Great Awokening’ drastically undermining our sense of British history over the last decade. What there has been is a greater appreciation of the role that slavery and slave ownership, alongside other forms of colonial exploitation, played in that history. If one thing stands out above all from this analysis of the IEA’s ‘book’, it is that different conclusions are reached according to whether research is driven by curiosity or by politics. Perhaps the most urgent question is how a short and superficial book could attract such serious attention in the British media? Think tanks and lobbying groups like the IEA, Policy Exchange, the Legatum Institute and Restore Trust do not do curiosity-driven research. They cherry-pick and decontextualise the research of others. Their work is driven by the conclusion they intend to reach, and not the other way around. As Lawrence Goldman says in the latest IEA attempt to defend the IEA’s stance, ‘We suffer from a rash of people who rush into print to use history to confirm their prejudices’.[25] Unfortunately we also have a media that seems skewed at present towards the amplification of their voices.

[1] Thanks to Patrick O’Brien and Pat Hudson for their inputs to this article.

[2] Never mind that the idea of a single path towards modern economic growth, associated with the modernisation theory of the 1960s, was rejected long ago.

[3] My emphases.

[4] https://x.com/K_Niemietz/status/1786338744418664679

[5] This chapter also helps address Niemeitz’ preoccupation with why Britain industrialised early on with the help of its empire and other European countries did not: ‘Whereas war and debt proved fatal for France, the wars that England fought allowed it to retain its control over global trade’.

[6] Telephone conversation with Patrick O’Brien.

[7] Personal correspondence.

[8] George Prinsep, ‘Remarks on the External Commerce and Exchanges of Bengal’, in K. N. Chaudhuri, The Economic Development of India Under the East India Company 1814-58, Cambridge University Press, 1971, 53. My thanks to William Owen who brought this work, and the Prinseps’ role in railway building to my attention.

[9] Extracts here from Alan Lester, Kate Boehme and Peter Mitchell, Ruling the World: Freedom, Civilisation and Liberalism in the Nineteenth Century British Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2021, 144-50.

[10] My thanks to Pat Hudson for these points.

[11] The otherwise excellent recent review of the literature by Mark Harvey and Nicholas Draper, which became available only after Niemietz’s book, overlooks many of Berg and Hudson’s insights on the later period, but reinforces their general arguments and the significance of their book.

[12] Berg and Hudson, Slavery, Capitalism and the Industrial Revolution, 6-7.

[13] Ibid., 9-10.

[14] Even Eltis and Engerman upon whom Niemietz draws quite heavily to minimise the role of the slave trade and the sugar industry specifically, conclude that ‘African slavery thus had a vital role in the evolution of the modern West, but while slavery had important long-run economic implications, it did not by itself cause the British Industrial Revolution. It certainly “helped” that Revolution along.’ They continue, ‘but its role was no greater than that of many other economic activities. In the absence of any one of these it is hard to believe that the Industrial Revolution would not have occurred anyway’. That is rather like saying that a cake comprised of various ingredients would have been a different cake with different ingredients. It does not alter that fact the actually-existing cake depended upon the ingredients brought together to make it. In the case of Britain’s industrial revolution, they concur that slavery was one of these ingredients.

[15] My emphasis. Paul Kennedy notes that in the 1880s and 1890s – at the height of the colonial scramble – only 2.3 per cent of British national income was being devoted to the armed services – about same as now.

[16] Private correspondence quoted with permission.

[17] Battacharya quoting Mokyr J. (2003). Accounting for the industrial revolution. In Johnson P., & Floud R. (Eds.), The Cambridge economic history of Britain (pp. 1–27). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

[18] Battacharya writes that ‘O’Brien completely missed the point that of the £10.50 million of imports from the periphery during 1784–1786 that he cites … nearly 50 per cent … came from Asia, most of which were bought with the Indian revenue directly or indirectly. These imports, then, were effectively free for Britons … If the transfer of wealth from India behind them is added to O’Brien’s estimates of profits from trade with the periphery, the contribution of periphery to aggregate capital accumulation in Britain during this period, using his methodology, could be, depending on one’s assumptions, as high as 70 per cent or even higher’.

[19] Cited in https://monthlyreview.org/2021/02/01/the-drain-of-wealth/

[20] Shashi Tharoor, Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India, London: Hurst, 2017.

[21] Battacharya gives a useful overview of the estimates made so far: ‘Furber (1948, p. 304) set out his formulation of the drain as follows: “the only true drain resulting from contact with the West was the excess of exports from India for which there was no equivalent import”. Furber estimated this drain to have been £11.8 million over the period 1783–1792 (at current prices), that is, an average of £1.3 million per annum. Other estimates of this drain include Maddison’s (1971) estimate of £100 million for the period 1757–1815; Hamilton’s (1919) and Sinha’s (1956) estimates of £34.5 million and £38.4 million, respectively, for the same period of 1757–1780; Burke’s (1981) estimate of £1 million per year for the 4 years ending 1780; and Habib’s (1974) estimate of well over £2 million for 1789–1790. A rigorous recent estimate is that by Cuenca Esteban (2001) for the period 1772–1820 whose figures show the “arguably minimum transfer” from India to Britain—in the balance of payments sense—reaching a peak of £1.01 million annually in 1784–1792.’

[22] Nick Robins, The Corporation that Changed the World, Pluto Press 2012, p206

[23] Alan Lester, Kate Boehme and Peter Mitchell, Ruling the World: Freedom, Civilisation and Liberalism in the Nineteenth Century British Empire, Cambridge University Press, 2021.

[24] Mark Harvey, Nicholas Draper, Britain’s Debt to Slavery: A Critical Review, History Workshop Journal, 2024;, dbae008, https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbae008. As noted, Berg and Hudson do this to an extent that Harvey and Draper could perhaps have noted more generously.

[25] As well as O’Brien’s 1988 paper and Engerman (see above), Goldman relies on Joel Mokyr’s argument that Caribbean slavery contributed little to the Industrial Revolution, but omits his follow up: that the slaver-based economy as a whole, mainly that of the US South’s cotton industry, was crucial.

Recent Comments