Thankyou for reading this EE blog, this post is representative at the time it was written.

There is a lot of talk about Active Learning and the importance of learning by doing, but isn’t reading a kind of doing? In my mind it is, but I am reminded too that research by Bartholomae, Petrosky & Waite (2017) suggests that real learning happens, ‘only when the authors are silent and you begin to speak in their place’ (page 272). So, as educators we have two key responsibilities related to reading, one is in setting the reading lists, and the other is to provide spaces for students to use the meaning of the text in their own contexts i.e. speak in the place of the texts. This might be where Active Reading comes in.

Active reading is a strategy of reading to understand and evaluate a text. It has been found to increase the joy people experience in reading, even amongst those who have found it a chore in the past (Tovoli, 2014). Here are five strategies for encouraging students to take an active approach to their reading.

Active reading strategies

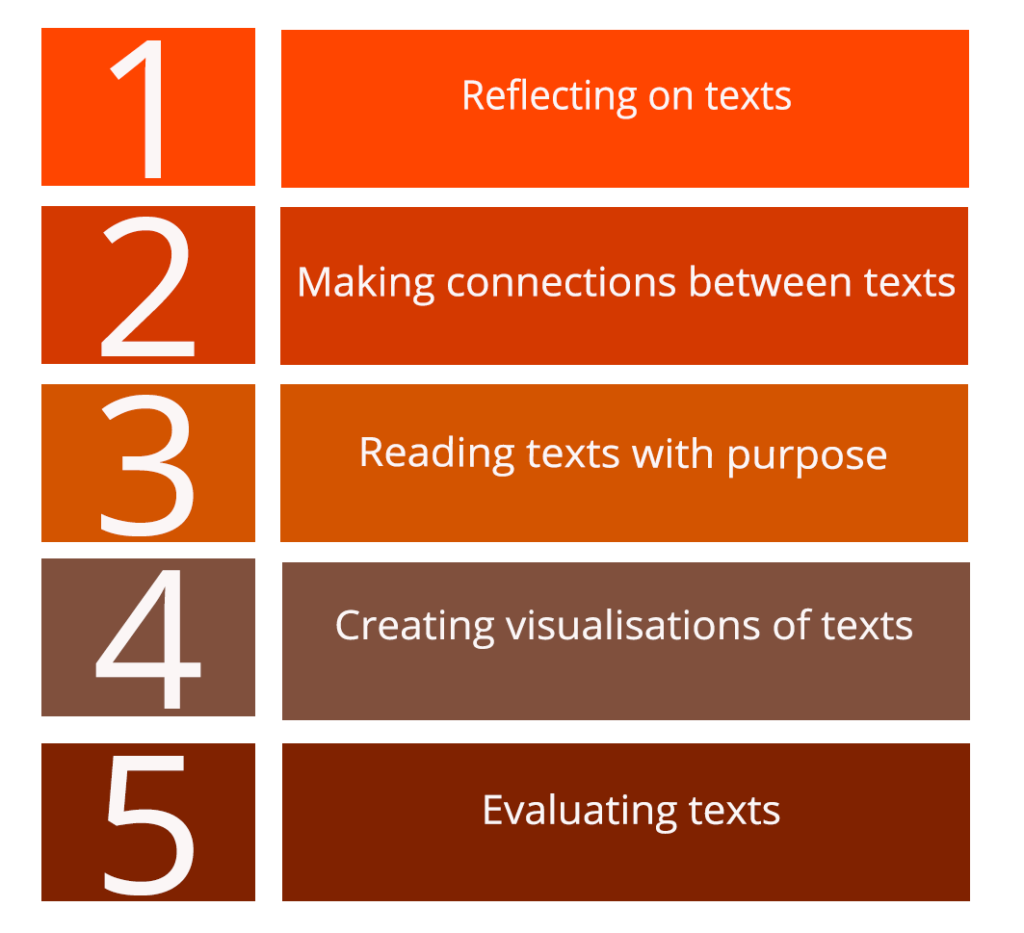

There are a number of different active reading strategies we can use with our students, helping them engage with their readings. If applied correctly they may help address some of the concerns brought up in the decolonising the curriculum agenda, by making reading relevant to personal contexts. The following is a non-exhaustive list of the kind of engagement we might ask our student to have with the reading:

- Reflecting on texts. Texts usually say different things to different people. One way to open up dialogue between students, who might otherwise be worried that they have misunderstood it, is to ask them to reflect on a text and to speak about it in the context of their own personal histories and experiences.

- Making connections between texts. Texts often support or contradict other texts. Asking students to compare and build connections between texts can help them to be more critical.

- Reading texts with purpose. Texts infer meaning. Asking students to read the text whilst considering what it means in other contexts can help students see how what they learnt from the text can be used in other scenarios and spaces.

- Creating visualisations of texts. Sometimes you can build pictures in your mind’s eye as you read a text. Asking students to share those pictures can increase their ability to recall the messages within it.

- Evaluating texts. Part of understanding a text is coming to understand their origins and credibility. Researchers have devised the CRAAP test in order to understand the value of a text. The acronym, apart from misspelling a rude, but relevant word, encourages the students to consider:

- Its currency: when the piece was written and why it was important then

- its relevance: its pertinence to the questions you have now

- its authority: the author’s qualifications to write on the topic

- its accuracy: the evidence that supports the text;

- and its purpose: the motive behind writing the piece.

Apps for Active Reading

Once we have decided the active reading strategy we want our students to use, there are a number of digital apps available to support them.

Apps for digital annotations

Many students have been actively annotating texts long before it was recognised as “a thing” and we see the evidence in old library books with underlined paragraphs and reflective notes scrawled in the margins. Nevertheless, we should not assume all students have this innate capability and opportunities to practice these skills in a formal way reduces barriers to learning and the gap between those who know how and those who don’t.

Digital texts provide new opportunities for text annotation. There are many digital annotation tools, which can be useful. Tools that also allow students to annotate PDFs and share them with peers include:

(use of these depends on the texts being free from copyright and able to be legally uploaded to these platforms)

- LiquidText (paid)

- Talis Elevate (paid. Foundation year students at Sussex have access to Talis Elevate)

- Hypothes.is (free, although there is a paid for version)

Apps for annotated bibliographies

Whilst exercises that require students to annotate text have become almost synonymous with active reading recently, they certainly aren’t the only way to encourage students to actively read. One exercise we can set for our students is the creation of annotated bibliographies. These are descriptions of the readings that the students create, keep and can refer to when needed.

There are a number tools that can allow you to create annotated bibliography and some of these allow students to build the bibliographies collaboratively. These include:

Apps for reading portfolios

Another exercise we can ask of students is to keep a portfolio of reflective notes on their reading engagement. Tools such as OneNote, Mahara and even text based tools such as Word, GoogleDocs and OneDrive can support this. Asking students to share their portfolio contributions with their peers via Canvas Discussions, Google Jamboards, Miro or Padlet can improve their engagement with the reading, while also removing the burden on us as teachers to provide feedback to each student. If you’re a student or a indeed a member of staff and want to start a portfolio, this online resource might help you.

Active Reading Projects

There are a number of active reading projects across the Higher Education sector.

- The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education is engaged in a large-scale research project investigating digital reading.

- The University of Lincoln are engaged in a “making digital history project” and are asking for teaching staff and students to contribute to their research by filling in this staff questionnaire and this student questionnaire.

- The library service provider, Talis, also has a long standing interest in Active Reading.

Whatever the tool, It is usually important that annotation is set as a task with a particular goal, such as those mentioned above, in order for the students to actually do it. If you would like students to get involved with Active Reading, contact the TEL team at tel@sussex.ac.uk.