Guest post by Lorraine Smith

Lorraine Smith is a Senior Lecturer within the School of Life Sciences, and sits within the subject disciplines of biochemistry and biomedicine. Smith’s teaching responsibilities are varied and cover modules spanning foundation through to Masters level. Smith is the course convenor for BSc Life Sciences (which is essentially foundation year) and convenes and teaches three of the modules within the course. This post relates to the foundation year and some of the strategies for social inclusion and engagement used during the academic year 2020-21.

The Covid 19 pandemic posed many challenges to teaching within higher education, both for students and teaching staff. The isolation, lack of normal social interaction, and lockdowns contributed to a decline in students’ mental health, general well-being and feeling of belonging. A recent study reports that at the start of lockdown (in April 2020), students felt significantly more socially isolated, more worried about family and friends, more worried about the economy, more worried about their future career, and more affected by personal problems that were usually ignored (Elmer, Mepham & Stadtfeld, 2020). Given these factors, I devised strategies, and worked with colleagues and students, to develop interventions to foster interaction and community between students on the foundation cohort.

Practicals

The Life Sciences course prepares students in both subject specialism and practical skills development. Given the inability to run in-person practicals for most of the 20/21 academic year, I developed online provision for my Applied Skills in Biology module using Canvas, the University’s virtual learning environment, and integrated several other approaches that sought to foster social connections and engagement.

The online baseline

Alongside fostering social connection, another important challenge was to make the online experience interactive and require students to engage with, and process data, as well as to demonstrate understanding of the practical skill associated with the activity. For each practical, I created Canvas pages providing specific information about the practical, embedded videos demonstrating techniques co-created with the teaching technicians, and I embedded Learning Science interactive tutorials. For each practical, I created bespoke quizzes, which students were required to complete before attending a post-lab Zoom; where students were invited to discuss their results, the limitations of experimental techniques, and apply their understanding to application questions.

Face to face or online

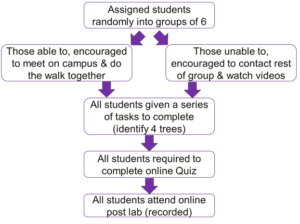

For the first practical, I developed an inclusive ecology-related experience that could be engaged with by students able to get to campus and meet others outside as well as catering for those who would only be able to engage online. At the beginning of October 2020, the UK had the rule of six meeting outdoors and many students were either isolating, at their home addresses or overseas, which led me to this flexible teaching approach. The primary objectives of this practical were to support students to settle in and to help students to make friends in week one . However the activity was also embedded within the subject discipline and was therefore relevant to the teaching and learning that took place during the subsequent ten weeks of the module. Figure one outlines the way that the practical experience worked.

The videos I created for the online students were very easy to make and upload onto Canvas. I made them on my phone and they were essentially showing students particular trees within the woods bordering Stanmer park, an area of open countryside adjacent to the University campus. These videos had a dual purpose, firstly they helped distance learners feel physically connected to the University and secondly, by highlighting particular parts of different trees, they encouraged students to carry out discipline-specific investigative work as students were required to determine which species of trees I was showing them.

Students purposefully had free reign to use whichever resource(s) they wanted to identify the trees, and I used this as an opportunity to discuss the sources they had used and to introduce the importance of academic sources within the online post lab. Students discussed the reliability of the sources they had used and this strategy appears to have enabled students to gain a better understanding of academic and non-academic references, in comparison to students from previous years. Evidence for this is suggested in the summative essays students completed within this module, where they demonstrated better engagement with reliable sources than the previous year, suggesting that this simple exercise had impact within assessments.

When questioned in the post-lab, students said that they had found this experience useful as an introduction to the location of the university and also used this as an opportunity to get to know each other. Student engagement with this module was excellent: 77% students engaged with the ecology practical canvas pages and 94% attempted the quiz questions.

Although students understandably missed the in-person practicals, the results of the Applied Skills in Biology exam (mean 68.3%) demonstrates that the learning outcomes were achieved using these online practicals.

Post-it practicals

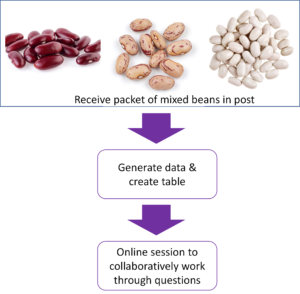

As lockdown continued into the second term, our teaching team wanted to provide students with some practical materials to physically interact with. We worked with our head teaching technician (Kristy Flowers) to develop packs that could be sent to students in the post. For my Genetics & Population Genetics module, we were able to send out packs containing specific numbers of three types of beans that students used to generate data to demonstrate the Hardy-Weinberg principle, Figure 2 illustrates the principle scheme of the Hardy-Weinberg practical that students would follow.

In essence, students received a pack of mixed dried beans in the post , were encouraged to read the background Canvas page of the online practical, and then complete the data generation part of the experiment (which required pulling out 20 pairs of beans to represent ‘matings’). I scheduled a Zoom meeting to go through the next steps and to work through the questions together, and it seems that this mixture of independent work and collaborative engagement were particularly effective here. It has been well documented that collaborative learning can be achieved in an online environment and that there are a myriad of pitfalls to setting students group work within an asynchronous framework (Roberts, 2003), so the strategy used here was purposefully synchronous and supportive.

In summary, student engagement was fantastic, and in the end of module evaluation there was a comment that it was the best part of the module.

Lessons learnt

There have been many challenges associated with the move to online only teaching but also many rewards in terms of developing new approaches to teaching. I don’t believe I managed to overcome all of the specific challenges relating to practical experience by implementing the methods described here, since there are elements that can only be gained by physically interacting with equipment. However, I did develop students’ understanding about the techniques and support their understanding of fundamental principles thereby enabling their achievement of the learning objectives. Aside from the module objectives the strategies implemented also encouraged student interaction and collaborative learning, which I feel has been really important during these times. I would have liked to have provided more post it practicals for students and if we ever have to go into lockdown again I would develop more resources for this, but there are obvious limitations in what can be sent through the post so it is not always simple or possible to translate a lab practical to a home version.

There are aspects of the online experience that I will carry forward into next year. In particular, the resources created for the modules will be used to support students’ understanding of the skills and techniques they will be learning in the laboratory, and I will keep the online post lab sessions so that I can encourage synchronous collaboration in a supportive way. I have definitely learned the importance of social inclusion and will be encouraging students to interact with each other more than ever!

References

Elmer T,. Mepham K., Stadtfeld C. (2020) ‘Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland’. PLOS ONE 15(7): e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Roberts, T.S. (ed.) (2004) Online collaborative learning: Theory and practice. Hershey, PA: Information Science Publishing.

Leave a Reply