Dr Emily Danvers

Conversations around teaching rarely happen beyond formal training opportunities that often take place early on in our careers. After this, and especially during term-time, space for talking in our busy working lives is often limited. Incidental corridor chats are seen to generate a collaborative and positive working culture and, for some, were mourned during the pandemic and its aftermath. Indeed, post-COVID (or maybe this was always the case?), we rarely have time to talk to our colleagues about anything at all. When it comes to teaching, who do we approach when things go well, or not so well? Who is talking? Who is listening? And who cares? This was the premise for our project, drawing colleagues together across the then newly formed Faculty of Social Sciences, to talk about how we facilitate conversations about teaching, and our wider working lives, to enhance a sense of community and belonging for staff.

The conversation theme was inspired by Jarvis and Clark (2020) whose work emphasises how the informality of a conversation about teaching flattens power relations and allows people to make meaning together without the intensity of an agenda or outcome. They position this work in contrast to formal teaching observations with their traces of surveillance, performance and measurement. Too often we rely on these individualised encounters to ‘develop’ teachers, where in fact, authentic conversations might more meaningfully transform teaching, where colleagues hear something, share together and be inspired by each other in the everyday. This reflects Zeldin (1998, p.14) who notes that: ‘when minds meet they don’t just exchange facts; they transform them, draw implications from them, engage in new trains of thought. A conversation doesn’t just reshuffle the cards; it creates new cards.

With the provocation to encourage transformation through talking together, Emily, Suda and Verona set up an initial launch event for all the faculty to generate some initial conversations about teaching. The questions and topics that emerged from this focused on the following questions.

- Why is community and belonging important for diverse academic flourishing?

- How and where is community and belonging created and developed?

- How might the labour of community and belonging work become visible, valued and rewarded?

The 12 colleagues who attended were afterwards put in cross-faculty threes and connected by email, with suggestions that they meet again to continue these conversations. As project leads, we were deliberately hands-off at this point, as the purpose of this project is to see if and how these conversations form organically.

A couple of months later, 5 of us met to blog together for the day, about our response to the questions, along with other themes that came up along the way. What we share in this blog collection is the story of our collaboration conversations.

In Jeanette and Fiona’s blog, they talk about what we can learn from student collaborations, which are often and rightly prioritised in the work of higher education.

In Suda and May’s blog they write about the value of time and space to slow down the academic pace and to generate community.

In Emily’s blog, she talks about the joy and challenges of teaching across different disciplines and how collaborations are structurally challenging.

What we learnt from this project is the ethics and timeliness of the conversation format, as a collegiate response to the complex and evolving challenges facing the sector, our students and ourselves as teachers. We all relished time to talk and think about the uncertain, the tricky, the everyday, the thorny, the unequal, the caring and uncaring practices – all of this important ‘stuff’ that sustains us as teachers but has no space in our working lives. We also did not only talk about teaching but about other collaborations that we value.

Our recommendation is that teaching (and other) collaborations should be exploratory and conversational rather than only a tool for appraisal, What we are seeking is regular open and meaningful dialogue about teaching and academic working lives that is not ‘done to academics at the behest of institutional leaders’ but conversations ‘with or among colleagues, characterized by mutual respect, reciprocity, and the sharing of values and practices’ (Pleschová et al, 2021:201).

References

Jarvis, J., & Clark, K. (2020). Conversations to Change Teaching. (1st ed.) (Critical Practice in Higher Education). Critical Publishing Ltd.

Zeldin. T. (1998). Conversational Leadership https://conversational-leadership.net/ [Accessed 15.07.2025}/

Pleschová, G., Roxå, T., Thomson, K. E., & Felten, P. (2021). Conversations that make meaningful change in teaching, teachers, and academic development. International Journal for Academic Development, 26(3), 201–209.

Getting the ‘social’ into Social Sciences: how can we learn from LPS student initiatives to build cross-faculty relationships?

Jeanette Ashton and Fiona Clements

The broader context

When the new faculty structure at Sussex was first mentioned, discussed further at university-wide forums and School and Department meetings, our reaction was perhaps similar to many others. Whilst ‘indifferent’ might be too strong, our thinking was that this was a decision taken at a university leadership level which probably wouldn’t change much on the ground, aside from potential pooling of resources in a challenging higher education climate. We felt that any changes we needed to make would filter down in time through our Head of Department, but that, in short, it would remain ‘business as usual’ for the Law School. The ‘Conversations on Teaching for Community and Belonging’ initiative by Emily Danvers gave us an opportunity to explore how the new faculty structure might enable us to develop supportive relationships with colleagues outside of our department, what that might look like and how it may help us navigate challenges going forward post the voluntary leavers scheme.

In the last few years of her role as Deputy Director of Student Experience for LPS, Fiona developed a number of initiatives which were well-received by the student body. In this piece, we consider how we might draw from those initiatives to develop a faculty-wide space, but with a staff rather than student focus. That is not to say that building faculty wide student relationships is not important, but that, as Ni Drisceoil (2025) discusses in her critique of what student ‘belonging’ means and who does that work, staff community and belonging often takes a backseat. We conclude with some thoughts as to how we might move forward.

Community and belonging sessions for students in LPS – what did we do and why did we do it?

For the last couple of years in LPS, we have hosted a weekly breakfast or lunch event for students. We know that very many of the students find that the peers that they share their first year accommodation with end up being some of their closest friends – both at university and beyond. Friendships are also forged at departmental level but, in addition, we wanted to give the students an opportunity to come together, informally, and meet students from other departments in the school.

The get together would happen in the same room, the student common room, at the same time each week. As the Law school runs a two week timetable, it meant that different Law students would be available to attend, depending on whether it was an even week or an odd week. There was a small group of students from each department who would come every week, but we also had new faces at every get together – students who had heard about the event, or students who just happened to be in the common room when the event was happening.

When we asked the students about their motivation for attending, they gave a variety of different reasons. It was interesting to note that some of the students came to the event with the intention of seeking advice (perhaps about managing workload, or how to tackle their reading etc). The students found that having a casual conversation with a member of faculty whilst sharing some food was a preferable option to pursuing the more formal route of booking an office hour with an academic advisor whom they may know less well.

LPS Staff events: what can we learn?

In thinking about faculty-wide initiatives, it’s important to consider what is already happening in schools and departments and what we might learn from that. In LPS, we have online school forums, which are well-attended by both academic and professional services staff and a useful way to catch up on what’s happening at School level. In terms of more socially oriented events, we have regular ‘Coffee and Cake’ sessions, which are not well attended. Without undertaking a survey, we can’t provide reasons for this, but it may be that this being a Head of School initiative and booked into our calendars, gives the impression that this is a space where we might be able to socialise, but not share concerns and ask ‘silly’ questions. Time is of course also a factor, with events such as these falling down the priority list as we juggle competing responsibilities. An open plan office space for professional services staff is perhaps more conducive to those conversations than the academic offices, so it could be that a faculty wide space for academic staff would provide an opportunity to have those conversations, with the benefit of perspectives as to what happens elsewhere.

What might be possible in the new faculty? Some ideas:

· Twice monthly scheduled spaces at different times on different days, and starting on the half hour, to maximise faculty availability

· A small cross-faculty team to rotate the ‘host’ role and spread the word in the different departments. As discussed above, a friendly facilitator was pivotal to the success of the LPS student initiatives

· Keep organisation minimal, and be clear that this is not a leadership initiative

· Clear comms on the purpose of the space: to drop in, meet people, share ideas and concerns, ask questions in an informal space without needing to schedule a meeting

· No need for food! No need for themes!

· Don’t be discouraged if no one turns up. These things take time.

References and further reading

Ní Drisceoil, V. (2025): Critiquing commitments to community and belonging in today’s law school: who does the labour?, The Law Teacher, DOI: 10.1080/03069400.2025.2492444

For more on community and belonging for students see Moore, I. and Ní Drisceoil, V. ‘Wellbeing and transition to law school: the complexities of confidence, community, and belonging’ in Jones, E. and Strevens, C. (Eds.) Wellbeing and Transitions in Law: Legal Education and the Legal Profession (Palgrave Macmillan 2023).

Slowing Down the Hamster Wheel: Space to Reflect and Create Communities.

May Nasrawy and Suda Perera

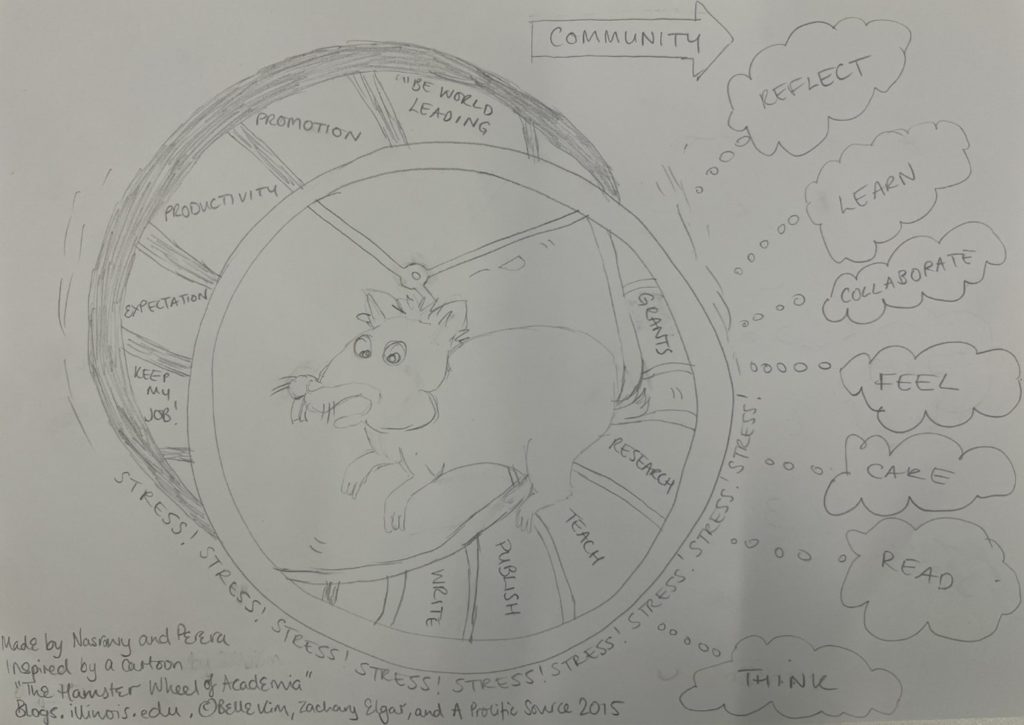

Since we’ve been teaching at Sussex, it’s felt like we’ve been in a state of perma-crisis: Strikes, pandemics, financial losses, have all contributed to a sense that we are on the brink of imminent disaster and we need to react quickly to avert an impending collapse. In this context a lot of pressure is put on as individual academics to do more and more with less and less. We need to teach more students and give them extra support even though there are fewer resources. We need to bring in more grants even though funding sources are shrinking, and publish more research in an increasingly narrowing field of “world leading” journals. Failure to do this, we are told, is an existential threat to the University and could result in more job losses, including our own. This sense of existential dread has meant that many of us feel like hamsters in a wheel – desperately scrambling from one task to the next in an attempt to just keep going and hope that eventually things will calm down. But the calm never seems to come, and in this highly individualised and reactionary wheel of toxic productivity, we seem to have lost a sense of community and belonging. In this blog we consider: Where in this endless cycle of work and crises is there space to think and reflect on why we’re doing this both as individuals and as a community? How can we break the vicious cycle of individualism and reaction and instead foster an environment where there is space to think and reflect in a collective and collaborative way to build the kind of University that we want?

By participating in the Conversations for Teaching for Community and Belonging, we have come to realise that there is a community of like-minded staff members who feel similarly , and that the answer to these questions begins with time and space. Time to step away from the hamster wheel of toxic productivity. Space to reflect on our individual identities and sense of purpose. Space to support and be supported by our colleagues. And from that space to foster a wider sense of community and belonging. This space requires us to have protected and meaningful time to just think and discuss with each other these bigger-picture and wider issues, which are not easily captured in bureaucratic processes. So much of the day-to-day running of the university relies on labours of caring and collegiality, and yet so much of this labour is hidden and not celebrated or even spoken about. We don’t want these spaces to be just one-off lip-service events or individualised awards, but rather collective spaces to talk through issues and share experiences with no expectation of a measurable output. By setting aside time for reflection, we argue we can move away from these feeling of constant reaction to immediate crises.

In the short time that we’ve had to engage in conversations with one another in this small project, we have been able to learn about what colleagues across faculties are doing in their teaching and research, and also share experiences that are point to issues of both concern and hope. We have been able to foster a sense of openness precisely because there is no sense that we are in competition for some sort of reward at the end, or that we have to produce something to demonstrate “value for money”. While we appreciate that much of what we do on the hamster-wheel of productivity is part of the job, we argue that it shouldn’t take up all the space, and should not be moving us away from other essential elements of our practice that require us to slow down to reflect, learn, collaborate, feel, care, read, and think.

Cross-faculty teaching: favour culture vs collaboration

Emily Danvers

Across the faculty of social sciences, many of us share research interests, professional expertise and academic knowledge that shape the topics we teach. When we met to collaborate on this project, for example, we found most of us teach about issues related to education, social justice, and globalisation. Yet we rarely teach outside the confines of our disciplines and departments. And where we do, it is through favours and friendships, rather than anything structurally organised. Our compartmentalised teaching arrangements often produce a culture that can work against collaboration.

A couple of years ago, Jeanette and I met through a shared interest in education for those of Gypsy, Roma and Traveller heritages. This was an area I research, and Jeanette had just started a community legal education initiative, Street Law, in partnership with the community organisation Friends, Families and Travellers. She asked me whether I’d talk to her students about teaching. Of course, I’d love to. I liked her. I liked the project. It was my area of expertise. Why not?

I’ve since done this a couple of times and get a huge amount from teaching Law students who I normally would never get to meet. Thinking about their contexts, disciplines and experiences and translating my pedagogical knowledge to them is also a useful exercise in understanding what and why I prioritise as an educator. But it isn’t in my workload. I don’t have to and am not, directly ‘rewarded’, in the very narrow sense of my own time. Jeanette confesses in our collaboration project that she feels guilty about asking me. But we work in the same university and now in the same faculty. Why shouldn’t we teach across these artificial academic boundaries?

This raises questions about how much of academic life might be sustained by these sorts of favours. It reminds me of the complicated emotions of gift-giving, where the receiver bestows something with surrounding norms of exchange and appreciation. On the one hand, forging positive relationships and having reciprocal practices of care are important ways to navigate academic work and its pressures (Frossard and Jeursen, 2019). Doing this cross-faculty teaching was joyful and enriching – a ‘gift’ to me as well as Jeanette. Also, an academy where we only did what was in our job description would surely fall apart!

But, on the other hand, these practices lead to under-recognition of labour or overwork. Academia has long been organised into silos – whether departments or modules – producing a sort of bento-box style organisation rather than a rich, interdisciplinary tasty stew. It is only when trying to foster collaboration through teaching across departments that we notice how the structures and cultures produce or preclude the kinds of interdisciplinary work we may find personally enriching.

In reflecting on this experience, what becomes clear is the tension between the joy and enrichment of interdisciplinary collaboration and the structural barriers that make such collaboration exceptional rather than expected. While cross-faculty teaching can feel like a ‘gift’—personally fulfilling and intellectually stimulating—it also reveals the fragility of a system that relies on goodwill rather than institutional support. When collaboration is sustained through favours rather than formal recognition, it risks becoming invisible labour, disproportionately carried by those with the capacity or inclination to give more than is required. If we want to foster truly interdisciplinary, socially engaged teaching that reflects our shared academic interests and values, we need to rethink how work is recognised, rewarded, and organised. Moving beyond the bento-box model of academic life will mean embracing new structures that not only encourage, but also sustain, collaboration across boundaries.

Frossard, C., & Jeursen, T. (2019). Friends and Favours: Friendship as Care at the ‘More-Than-Neoliberal’ University. Etnofoor, 31(1), 113–126. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26727103

Leave a Reply