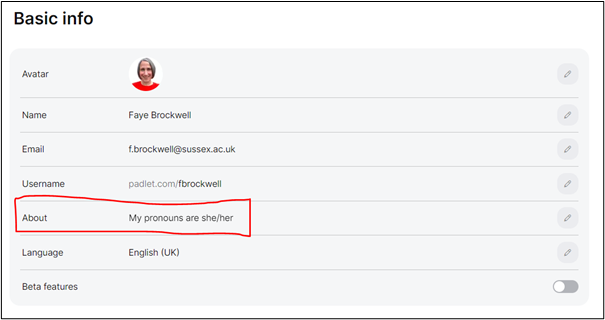

by Laura Clarke, Academic Developer, University of Sussex

When I taught in my previous institution, we used portfolios as a summative assessment for students as well as a means to evaluate instruction. We scored the portfolios based on a rubric and quantitative data was collected for various stakeholders. While this approach to using portfolios was useful for the institution, I felt that it missed a valuable opportunity to engage students in their learning.

While this approach to using portfolios was useful …

I felt that it missed a valuable opportunity

to engage students in their learning.

Portfolios can serve a dual purpose, catering to both Assessment of Learning—a conclusive assessment focused on summarising and evaluating overall student performance—and Assessment for Learning—an interactive and formative student-centred approach that prioritises ongoing assessment. Paulson and Paulson (1994) delineate two categories of portfolios that correspond to the objectives of Assessment of Learning and Assessment for Learning: positivist and constructivist, respectively. Positivist portfolios “assess learning outcomes and those outcomes are, generally, defined externally,” which “assume[s] meaning is constant across users, contexts, and purposes”. This approach views the portfolio as “a receptacle for examples of student work used to infer what and how much learning has occurred” (p.8). By contrast, the constructivist portfolio is “a learning environment in which the learner constructs meaning. It assumes that meaning varies across individuals, over time, and with purpose.” Here, “the portfolio presents process, a record of the processes associated with learning itself” (pp.8-9).

Positivist portfolios emphasising Assessment of Learning are usually structured around a set of outcomes, goals, or standards and are used to make high-stakes decisions. Within constructivist portfolios, students choose specific artefacts to narrate the tale of their learning journey, and these portfolios are employed primarily for formative rather than summative assessment purposes.

With Curriculum Reimagined, the University of Sussex is exploring new forms of authentic and flexible assessment so that students are given accessible opportunities to explore their ideas, interests and preferences within their learning. Portfolios can be a powerful vehicle for learning if they transfer responsibility for learning from the teacher to the learner. If we want to develop inclusive assessments that give students the opportunity to take ownership of their learning, it is important to balance both product- and process-oriented portfolios.

Portfolios can be a powerful vehicle for learning if they transfer responsibility for learning from the teacher to the learner.

Here are some recommendations for how to leverage portfolios to enrich the Assessment for Learning process:

- Give learners the opportunity to choose between assessment modes and to decide which artefacts best serve as evidence of their learning and development. Keep in mind that it is important to consider the equity of effort, standards, and feedback when offering students choice in assessment modes.

- Include a reflective component that encourages students to reflect on how the evidence they have selected demonstrates an evolution in learning. As reflection poses a new and challenging skill for many students, it is advisable to provide them with sample frameworks for reflective writing well in advance.

- Encourage students to incorporate proof of their ongoing learning process. This may involve submitting earlier drafts of finished assignments, engaging in a thoughtful review and reflection on feedback received for these drafts, and providing an explanation of the steps taken to incorporate feedback and enhance their knowledge and comprehension.

- Motivate students to repurpose the content of their portfolio for integration into a different kind of portfolio, like one designed to bolster a job application. Discuss with them the unique purposes such a portfolio would serve in the context of employment.

- To ensure that students recognise the value of creating a portfolio, it should be easily adaptable. Ideally, the portfolio should remain accessible to learners even after they have completed their time at an academic institution.

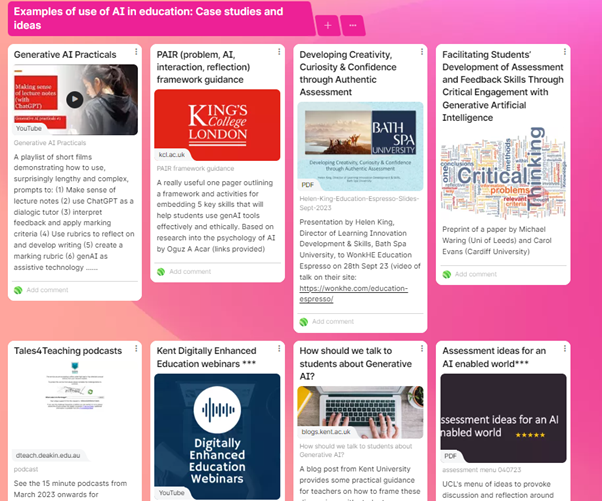

Educational Enhancement’s Academic Developers are developing resources to help instructors implement portfolios in their courses and modules. Please contact your School’s Academic Developer for support in developing and implementing portfolios that balance the goals of Assessment of Learning and Assessment for Learning.