Educational Enhancement are excited to announce the launch of a Teaching and Learning with Artificial Intelligence Community of Practice (AI CoP). Here I’ll explain why, in addition to the many brilliant groups and networks within Sussex and beyond, we’re launching our own AI CoP, details of the first CoP meeting on 4th December, and how to get involved.

What is a Community of Practice?

Chat GPT tells us that an educational community of practice (CoP), “refers to a group of educators, teachers, students, and administrators who come together around a shared interest in a particular educational domain or area of practice. The goal is to collaboratively improve teaching practices, enhance student learning experiences, and foster professional development within the educational community.”

Why an AI Community of Practice at Sussex?

Since the launch of the first free-to-use generative AI tools in the winter of 2022, universities, governments, individuals and organisations have been reflecting (with varying degrees of interest, excitement or concern) about AI’s impact on how we live, work and learn.

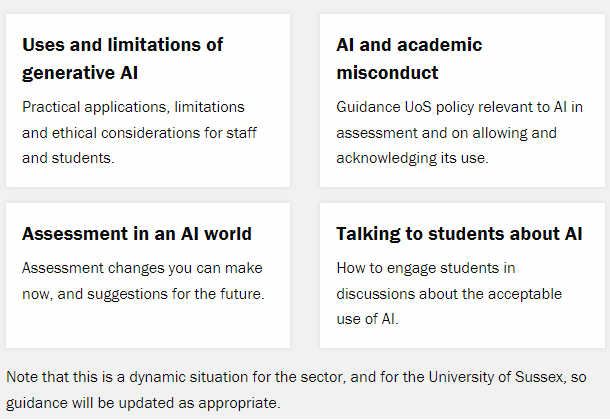

Universities and HE quality assurance agencies and regulators in the UK and across the globe have responded in broadly the same way, clarifying academic regulations and providing guidance on how staff and students might use these tools safely, ethically and also creatively. See, for example:

- The University of Sussex Guidance on using AI in teaching and assessment

- The QAA briefing in May on ‘Maintaining quality and standards in the ChatGPT era’ and their response, in September, to the Department for Education’s call for evidence.

- The Russel Group Principles on the use of AI in education published in July

Also, more than ever, practitioners have been sharing their concerns, along with examples of how they are adapting their teaching, learning and assessment, both to mitigate the worst impacts of AI and to re-think what and why they teach and the purpose of assessment. See, for example:

- The brilliant, and growing, playlist of Digitally Enhanced Education Webinars organised by Kent University

- Deakin University’s Tales4Teaching podcasts from April 2023 onwards.

We’ve been collecting all of these resources, and many more, on the University of Sussex Teaching with AI collaborative Padlet.

However, a collaborative Padlet simply isn’t enough.

For example, look at the Russel Group of Universities’ five principles, created to help universities ensure students and staff are ‘AI literate’:

- Universities will support students and staff to become AI-literate.

- Staff should be equipped to support students to use generative AI tools effectively and appropriately in their learning experience.

- Universities will adapt teaching and assessment to incorporate the ethical use of generative AI and support equal access.

- Universities will ensure academic rigour and integrity is upheld.

- Universities will work collaboratively to share best practice as the technology and its application in education evolves.

What ‘AI literacy’ or ‘effective use’ and so on might mean and how these principles will be enacted remains hotly debated, poorly understood and effectively untested. This exemplifies how the impact of generative AI on education can be defined as a wicked problem. Such problems are complex, hard to define, are intractable (they have no stopping point), there are no elegant solutions or right or wrong way of solving them, they are intertwined with many other problems and responses to them may have unforeseen impacts.

Leadership researcher Keith Grint argues that the more uncertain we are about the solution to a problem, the more wicked it is, the more we need collaborative leadership and many experimental and ‘clumsy’ solutions. We hope that the AI community of practice will create the space needed within Sussex for such solutions and leadership to emerge. A space within which people can ask questions, stay updated with the latest developments, build networks and contribute to the overall advancement of teaching and learning at Sussex and beyond.

How will the AI CoP work?

The first meeting of the AI Community of Practice will take place 14:00-15:30 on 4th December 2023 in the University Library Open Access Space (on the ground floor just past the Library help desk). Please come along early to avail yourself of tea/coffee and, maybe, some mince pies. You’re also welcome to listen along online if you need to.

Our new Provost, Professor Michael Luck, the founding Director of King’s College London’s Institute for Artificial Intelligence, will kick off the first meeting, in which we also plan to share briefly some insights into the journey of the sector and University so far and some quick-fire examples of practice within Sussex. We will also facilitate a discussion of where colleagues are now, what they need most from the community and approaches we can take within the CoP to facilitate knowledge sharing and collaboration.

Share your great practice:

If you’re trying something new with AI in your teaching or assessment, and are happy to share your experience in a 5-minute lighting talk at the December CoP, then please get in touch!

Can’t attend?

- Join our AI CoP mailing list for updates by emailing Simona Connelly

- Share great links and via the University of Sussex Teaching with AI collaborative Padlet.

- Submit a Case Study of your practice to the ‘Learning Matters’ blog (its quick and easy and we will help you with it!).

We hope to see you there!