In this case study, John Masterson, Senior Lecturer in World Literatures, talks about co-created learning communities and his module ‘Decolonising the Curriculum: Literature and Theory of the Global South’ (Q3309).

What I did

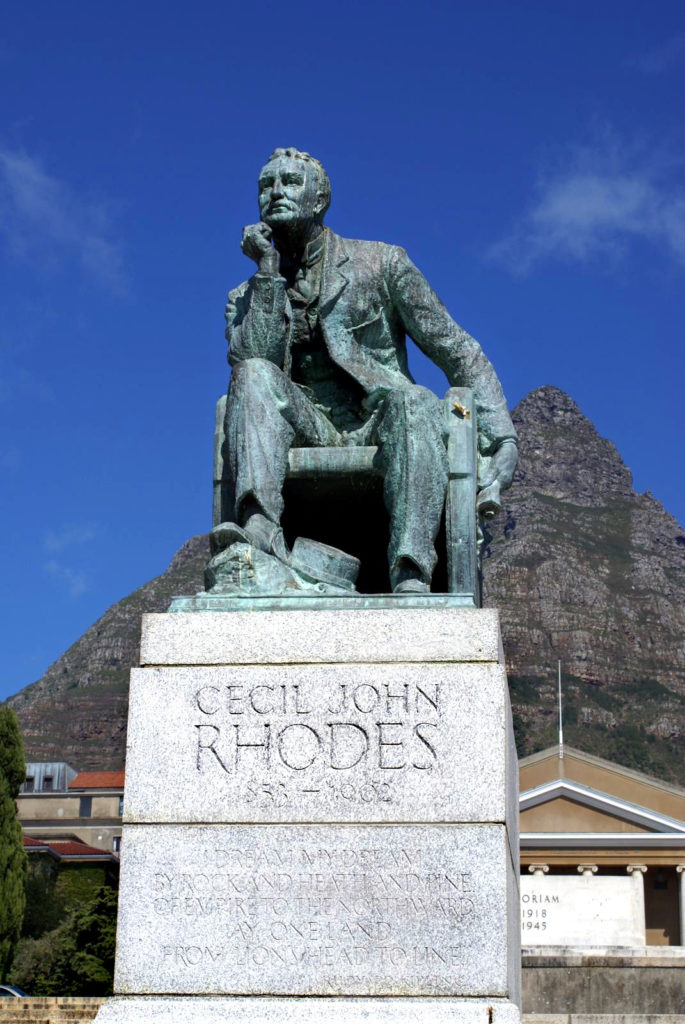

I was keen to offer Sussex students the opportunity to engage with their compatriots in the ‘global South’ to discuss how and why decolonising agendas might play out differently in different, contextually specific locations. Having worked at Wits University in Johannesburg prior to joining Sussex, I have important connections in South Africa, and given that the Rhodes Must Fall campaign initiated by students at UCT was the catalyst for broader Fees Must Fall campaigns in the country, I created a module that enabled Sussex students to talk to their contemporaries in Johannesburg. These conversations helped us to consider how and why literature and more critical interventions from the ‘Global South’ interrogate some of the founding tenets of contemporary theory.

Why I did it

The module was conceived at a time when the School of English, more broadly, embarked on a wide-ranging curriculum review. Given my teaching and research interests in postcolonial and/or transnational and/or global literary studies, I was keen to expand our offerings in these areas. This module embodies the commitment of the School of Media, Arts and Humanities to embedding the values of equality, diversity and inclusion in the curriculum as part of socially informed conversations with its diverse student community.

Impact and student feedback

At the heart of this module is thinking about how and why the debates we’re engaging in, in a predominantly academic setting, are both shaped by and have the potential to inform the world beyond the university. Students were able to see this by talking to their contemporaries in South Africa about how they put their lives on the line by participating in these protests on their respective campuses. By establishing these properly collaborative discussions, students began the work of unpacking/deconstructing the sense that knowledge production is the sovereign possession of those in the ‘Global North.

Challenges

The key challenges have been mainly logistical. The aim to involve students in curricular co-creation is laudable but, having run the module for three years now, there are planning implications. As it stands, the module runs in the final term of the final year of undergraduate study. The vast majority of students are, rightly, preoccupied with their final dissertation. As I don’t get to work with them until the Spring term, and reading lists need to be in well in advance, it is a challenge to square this circle. Another key issue, in terms of working with South African students as colleagues, is time, resources and synchronisation. Trying to find times that suit both Wits and Sussex students has been tricky, as has technological provision/reliability. South Africa was particularly impacted by the COVID pandemic and, having spoken to colleagues there, the HE ripple effects are still being felt in a number of ways. That said, I don’t want to give up on this collaborative aim. Given that the module is designed to introduce students to other, under-represented voices and alternative practices, the fact that I lead on it, given my own institutional and other positionality, is a rather intractable problem. It would be great to have other bodies and voices involved in the pedagogical arena itself. As colleagues and students are so stretched in terms of time and resources/remuneration, I can’t in good faith ask someone to do something for nothing. A final issue raised by students over the course of the module is the notion that it can’t live up to its name. Many have made the entirely valid point that, just because you have ‘Decolonising the Curriculum’ on your books, it is still bound by the various structures and strictures of the neoliberal institution. To what extent is ‘Decolonising’ just a token gesture? A forthcoming iteration of the module will be called, rather more generically, ‘Decolonisation and Literature.’

Future plans

I am on research leave in January, so the module won’t run in 23/24. This is perhaps no bad thing. In light of some of the challenges set out above, I want to explore the possibility of making more connections between the privileged spaces of our lecture and seminar rooms and the world beyond, both locally and internationally. I do believe the South African connection can be made to work, but I also want to consult students on how we might take some of the more theoretical questions swirling around ‘decolonisation’ into cultural and political spaces in Brighton. If there were to be more resources to hire colleagues with expertise in non-European and non-American literatures, not to mention languages, that would also allow for a more collaborative pedagogical and practical approach.

Top 3 tips

- Involve students from the outset. Listen to what they’re asking for and how they’re approaching this. Be prepared to engage them in any honest conversation about what is/has been offered in the past and why.

- Be willing to break out of your own academic silo. Consider models of ‘best/better practice’ in other institutions, both nationally and internationally

- Leave one or two ‘blank’ weeks, in which students determine the content/focus of the teaching for those sessions. This helps to further centre the student voice.

Leave a Reply